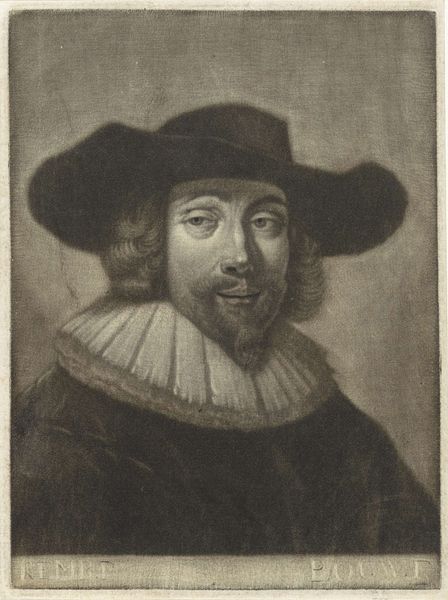

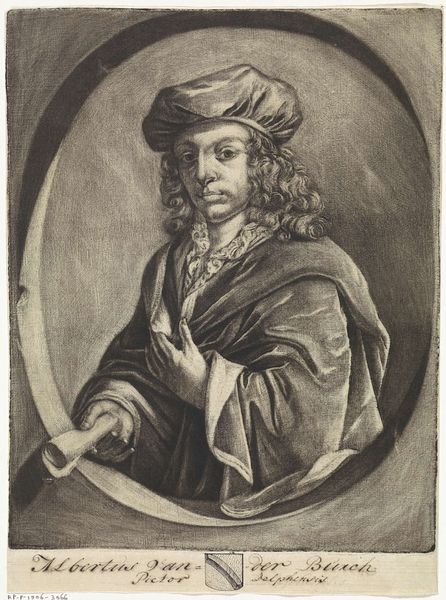

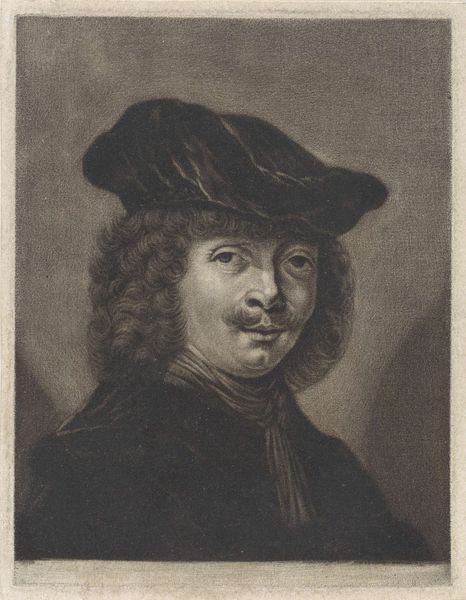

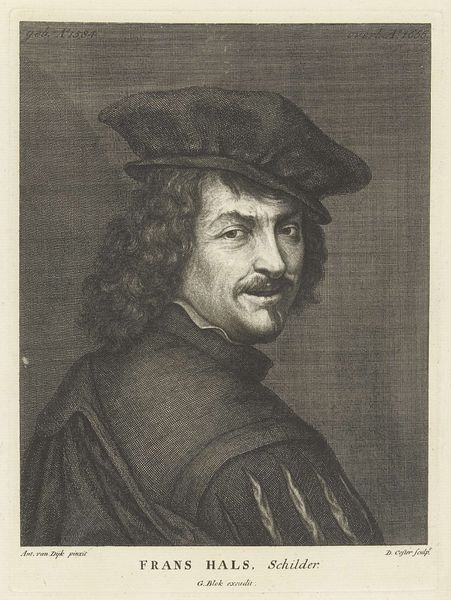

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 227 mm, width 172 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

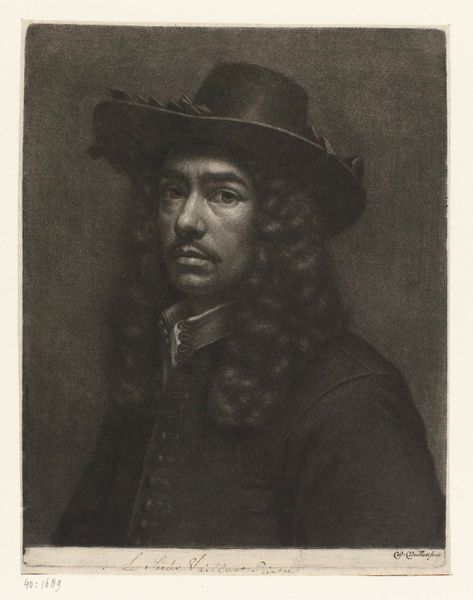

Editor: Here we have Jacob Gole’s "Portret van Adriaen van Ostade", dating somewhere between 1670 and 1724. It’s an engraving, a print. The face looks tired or melancholy somehow, even though it’s quite a formal portrait set within an oval frame. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: Well, let's consider the socio-political context. This portrait functions as a visual record but also as a piece of self-promotion for both artist and subject, right? How does the format—a printed engraving—influence its potential audience and impact compared to, say, a unique painted portrait? Editor: That's a great point. Prints were more accessible, weren't they? So, more people would see it, and maybe that increases the artist’s and subject’s status in society. Curator: Exactly. And what does it tell us about the evolving role of the artist and the art market during the Dutch Golden Age, when art began to be appreciated by a wider audience beyond the elite? Editor: So, it’s not just about individual skill, but also about navigating the market and building a reputation, which this engraving helped facilitate. I suppose that impacts how we interpret the "tired" look - perhaps it is part of carefully constructed persona. Curator: Precisely! By thinking about its production and circulation, the portrait opens to reveal social, economic, and institutional meanings, beyond the mere representation of a face. Are we seeing Ostade the artist, or Ostade the brand? Editor: I see your point. Considering how it was made and distributed changes everything. I had only been thinking about individual expression, but now I get the importance of its broader impact in the Dutch Golden Age art world. Curator: Glad I could broaden your perspectives. Every element within art has political connotations that deserve scrutiny.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.