photography

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

river

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

old-timey

#

orientalism

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 211 mm, width 270 mm, height 469 mm, width 558 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

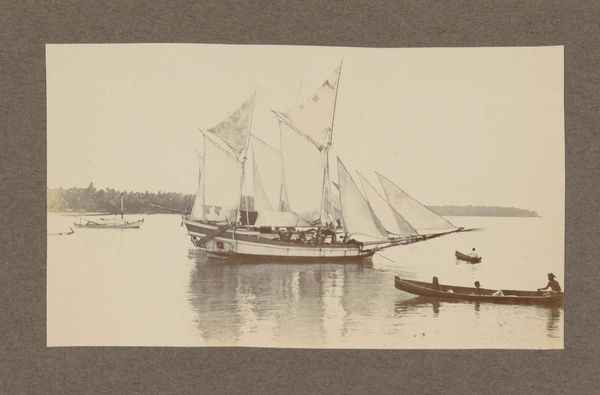

Curator: This striking photograph is titled "Dahabiya op de Nijl" by Jean Pascal Sébah, dating from sometime between 1888 and 1895. The print presents a detailed view of a Dahabiya, a traditional Nile riverboat. Editor: My immediate impression is one of stillness and a palpable sense of history. The tonal range is quite limited, giving the entire scene a somewhat dreamlike, sepia-toned quality. Curator: Sébah, operating from his studio in Cairo, capitalized on the burgeoning European fascination with Egypt, catering to the tourist trade. These photographs were often bound in albums and sold as souvenirs, documenting travels along the Nile. Consider the market for these images; they weren't just aesthetic objects, but commodities deeply entangled with colonial power dynamics. Editor: Absolutely, and you see that reflected in the careful composition. It’s not just documenting a boat; it’s selling an image of a romantic, exotic East, carefully constructed for Western consumption. The level of detail afforded by the photographic medium would've been particularly alluring. Note the textures of the rigging and hull. Curator: Indeed. The materials used, like the photographic paper and chemicals, speak to a complex global trade network that enabled the production and dissemination of these images. Each print depended on the labor of photographers, developers, printers… even the subjects captured had an unseen stake. How do you think this plays with the history? Editor: That’s critical. This particular image reflects the Orientalist aesthetic popular at the time, shaping European perceptions and perpetuating a romanticized vision of the Middle East. This seemingly objective documentation reinforces the exotic other, impacting political and social realities even today. Look how staged the figures on the boat appear. Curator: I'm particularly interested in how Sébah presented his images. The framing of the print as an artistic product transformed this craft object into something of higher art. What did the visitors consume: an artifact of travel or something meant to be observed in parlors and institutions back home? Editor: Food for thought, as we're confronted with a photograph whose afterlife remains ever complicated by its relationship to imperialist practices. Curator: I find myself pondering all the lives and labor encapsulated in the final piece as it remains on display here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.