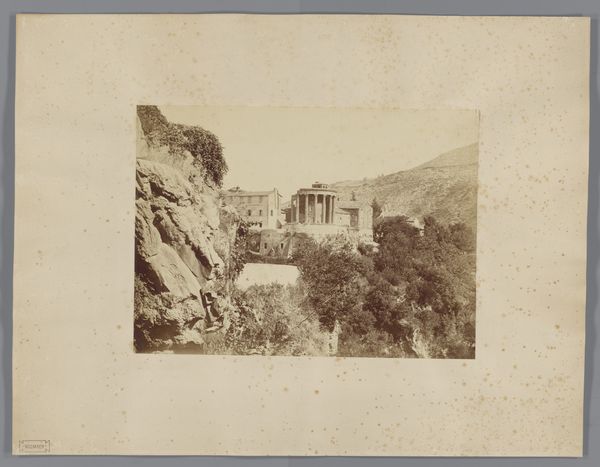

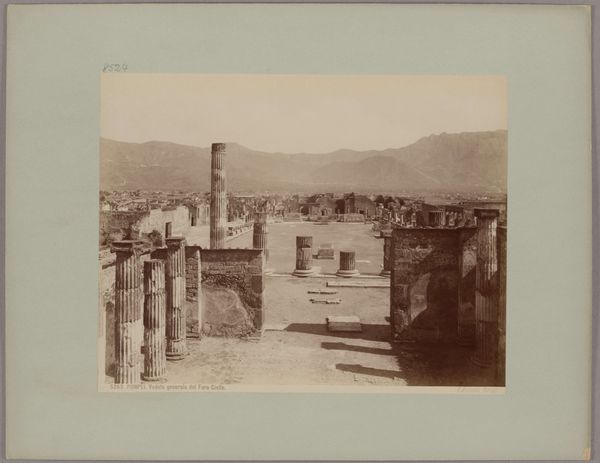

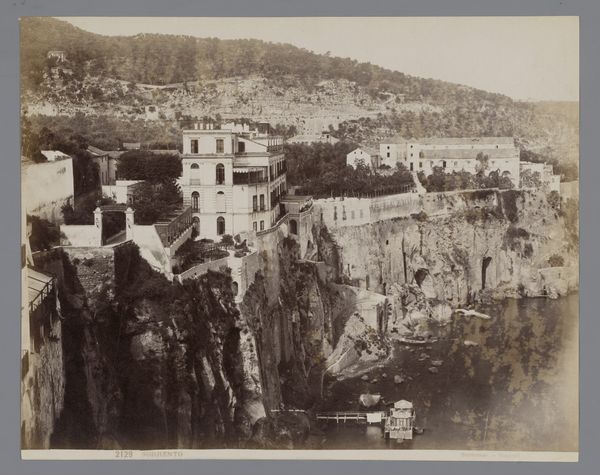

Gezicht op de ruïne van de tempel van Venus of Diana bij Complesso archeologico di Baia before 1879

giorgiosommer

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 201 mm, width 246 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Giorgio Sommer’s “View of the ruins of the temple of Venus or Diana at Complesso archeologico di Baia," a gelatin silver print, pre-dating 1879, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately striking. The tonality imbues the entire scene with a wistful quality. It's quite compelling how the ruins seem both imposing and delicate at the same time. Curator: Sommer’s composition expertly balances these architectural remains against the backdrop of the natural landscape. The strategic placement of the ruins allows for a reading that engages both the verticality of the ancient structure and the horizontal sweep of the distant sea. Editor: I'm more intrigued by the process of creating this gelatin silver print. Imagine the labor involved: mining the silver, creating the emulsion, painstakingly coating the paper. It is also vital to note that these kinds of archaeological missions in southern Italy were intrinsically linked to an increase in exploitative labor, with local diggers frequently laboring without permits or even contracts, making paltry sums to uncover pieces for an art market driven by foreign wealth. Curator: Interesting. However, note how Sommer captures light and shadow, defining form and texture and also adding to the atmospheric depth that contributes to the sublime effect typical of Romanticism, a period in which humans seek an experience surpassing anything our human-based reason and knowledge can muster. Editor: I am not sure about "sublime." The image itself acts as evidence of the raw materials used, reminding us that resources must be gathered, modified, and manipulated to represent such Romantic landscapes. It exposes the industrialization of image-making, especially with how widespread archaeological documentation photography had become in Europe by this period. Curator: While I concede that the photographic process itself holds interest, to overemphasize that detracts from the visual language used. The artist's choice to frame these decaying structures, for example, fosters a profound meditation on time and the transience of civilizations. Editor: But to ignore how the image came to exist limits our grasp on its significance! It’s a romantic scene dependent on resources and often human exploitation to take that initial form and achieve what you claim to be sublime. Curator: Perhaps there's room for both views. One can appreciate the aesthetic achievement alongside a critical assessment of the medium’s conditions. Editor: Indeed. The photograph, both as art and artifact, invites us to look deeper—past the surface to what constitutes our idea of ancient beauty and culture, to recognize labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.