Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

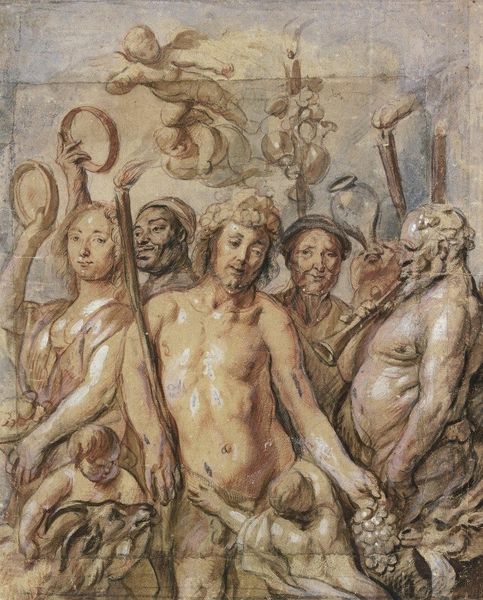

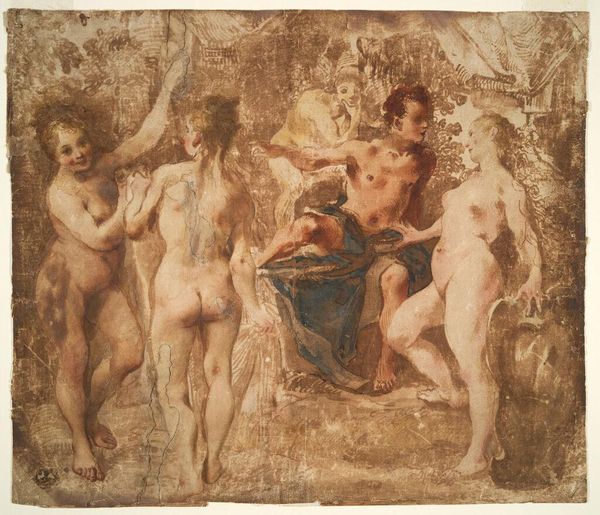

Curator: Looking at Edward Burne-Jones's "Helen Captive in Burning Troy," dating from 1870 to 1872, what immediately strikes you? Editor: A sense of subdued chaos, I suppose? The red and ochre palette feels like smoldering embers, and the figures are densely packed, conveying a feeling of claustrophobia and dread, but everyone is naked so is that just my projection? Curator: The monochromatic color scheme, achieved using oil and tempera, effectively creates the oppressive atmosphere you mention. Burne-Jones used layering techniques here that are common in his other works. His interest wasn't as much the event but more of the creation of a mood for the viewer. Editor: That "mood," as you call it, hinges on representing female bodies as spoils of war. Even amidst destruction, the patriarchal gaze persists, framing Helen as the ultimate prize. The image aestheticizes trauma while denying agency. It seems like the labor of crafting this picture normalizes viewing women’s pain. Curator: You make an interesting point; the labor invested in creating this image—grinding pigments, layering tempera, posing models—becomes complicit in representing women’s pain. Yet the historical context also needs consideration, given Burne-Jones was critiquing Victorian ideals with classical narratives. Editor: Context doesn't negate impact. This image feeds into a long history of representing women as symbols, devoid of their own experiences during conflicts and is consumed as decoration by the upper class. How do we reconcile enjoying something that stems from real suffering? Curator: That’s a discomforting challenge the painting throws up, one we cannot—and shouldn't—easily resolve. We, today, are invited to question how such subjects were—and continue to be—manufactured for art. Editor: Right. So, engaging with this work, then, demands an interrogation of how aesthetics, materials, and historical narratives can obscure violence against women. It forces us to ask: whose stories are being told, and at what cost?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.