print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

christianity

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

christ

Copyright: Public domain

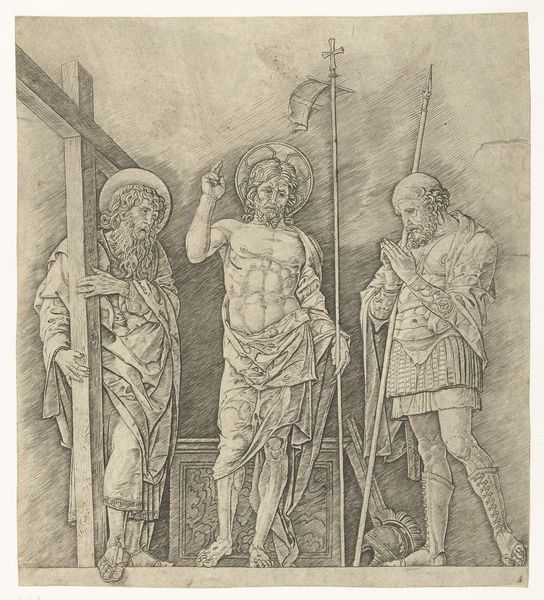

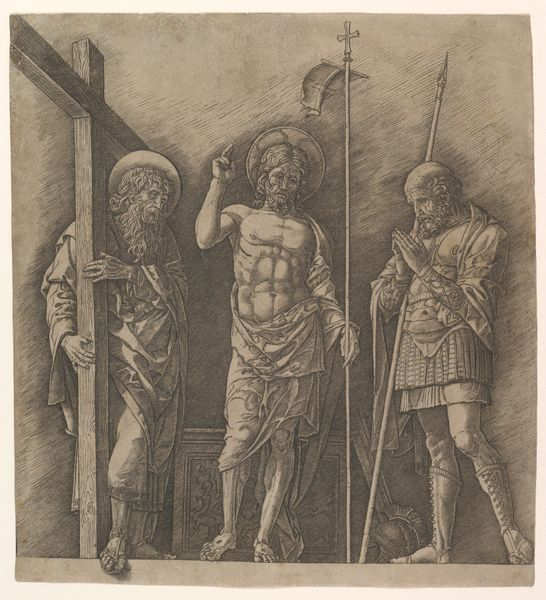

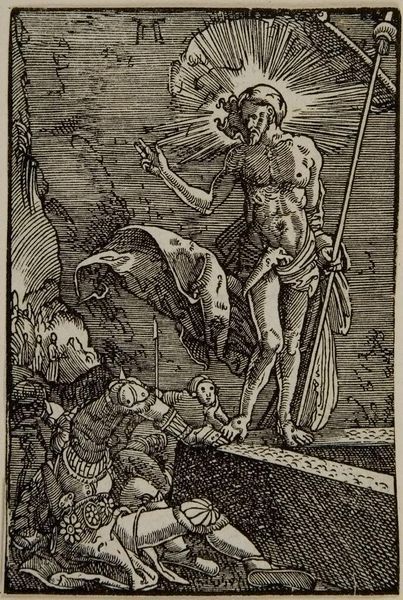

Curator: This engraving, "The Resurrected Christ between St. Andrew and Longinus," dates back to about 1475 and is attributed to Andrea Mantegna. What do you make of it? Editor: It's strikingly stark. The use of line and shadow creates this somber, almost severe mood, yet there’s also this palpable sense of power emanating from the central figure of Christ. It feels… purposeful, but maybe a little unsettling. Curator: That starkness comes partly from the engraving technique. Mantegna, of course, was hugely influential in Renaissance printmaking, popularizing its spread to a wider audience, and prints such as this were relatively new means for art distribution and reception. He's presenting a very idealized, muscular Christ, framed by St. Andrew and Longinus. What can you gather from the company Christ keeps here? Editor: Well, positioning Andrew with the cross hints at sacrifice, faith and suffering. Then you have Longinus. Interesting he's included him, the Roman soldier traditionally identified as the one who pierced Christ's side. His presence suggests acknowledgment, atonement maybe even a shifting power dynamic between religious and secular authorities of the time. Curator: Indeed. And there's been much debate surrounding Mantegna's interest in Roman antiquity, from the attire to the classical references in how Christ and his companions are rendered. But considering the socio-political landscape, how might viewers have perceived this idealized, resurrected figure? Editor: It's a challenge, certainly to deconstruct centuries of iconography. We've been trained to view these images through a singular lens. To challenge those notions means facing not just centuries of art, but also socio-cultural programming. The intentionality, for example, is loaded when thinking about religious power dynamics. Curator: It serves to remind us of the Renaissance context in which Mantegna was operating. He uses a contemporary means, that is printmaking and engraving, for very powerful political reasons: it provides a platform to communicate very relevant commentaries of religious themes. The role and iconography that comes with Christianity takes precedence. It's quite impactful. Editor: Definitely. Reflecting on the intersection of religious power, cultural transmission and evolving art forms offers some complex context for experiencing it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.