photography

#

portrait

#

toned paper

#

landscape

#

photography

#

19th century

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 162 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

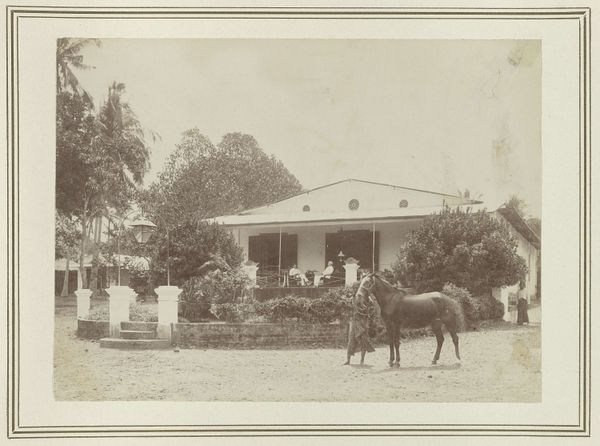

Curator: This photograph, "Vrouw en zoon voor het huis aan de Wilhelminastraat," was taken in 1916. Editor: The tones immediately suggest a faded, sepia world, a snapshot of lives lived long ago. There is a stillness to the composition—very balanced, symmetrical, a bit static even. Curator: Well, that static quality, I think, speaks to the very formal modes of portraiture at the time. This wasn't casual. It was a constructed representation meant to project a particular image of the family and their place within this society. Notice how the house serves as a backdrop. Its very construction involved specific labour and material sourcing processes representative of Dutch colonial infrastructure. Editor: Yes, the house looms almost like another character. Its design features--the columns, the ornate decorations under the eaves-- speak to a calculated aesthetic. The formal elements tell their own story. I keep returning to the contrast between the geometric structure of the building, and then the more organic palm trees slightly blurred by the limitations of photography at the time. Curator: And what about the clothing? That stark white, both a practical and symbolic material marker—perhaps reflective of its cost— but also of the specific cultural standards they're projecting. Their attire is as much a part of this narrative as the bricks and mortar. There's labor embedded in maintaining these appearances; consider where the raw materials originated from and the human resources that played a role in their labor. Editor: Formally speaking, the photograph draws the eye directly to the woman and child by contrast. It has to do with how they stand out against the dark entry, with a clever placement right in the intersection of geometric and organic patterns that immediately highlight them as figures within the scene, especially within the rigid structure of that period and location. The architecture encloses them, creates a frame and a focus. Curator: Right, and if we look closer at that framing, what we can reveal are colonial power structures subtly coded. Everything from architecture to textile materials signals a highly constructed visual field dependent on specific historical production processes. Editor: A scene seemingly simple, but the photographic elements within do possess significant complexity of the age. Curator: Indeed, analyzing production means, consumption and their impact is one step closer to unlocking greater perspectives. Editor: Looking closely does reveal so much hidden within, and changes my first quick glance, the emotional temperature does slowly change.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.