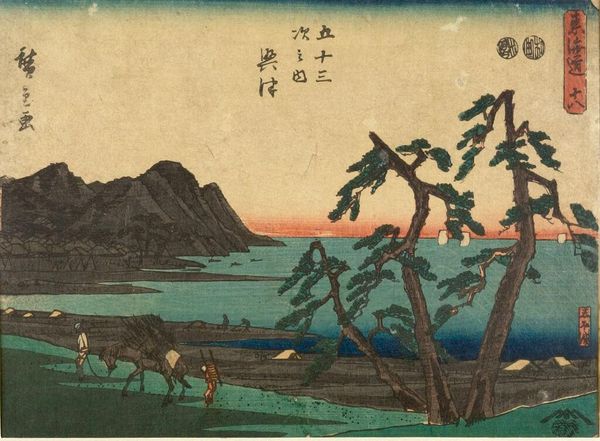

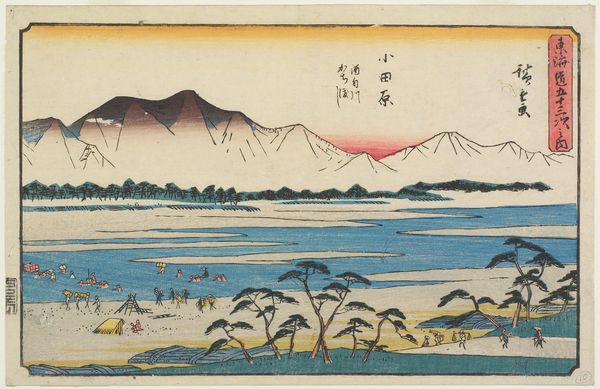

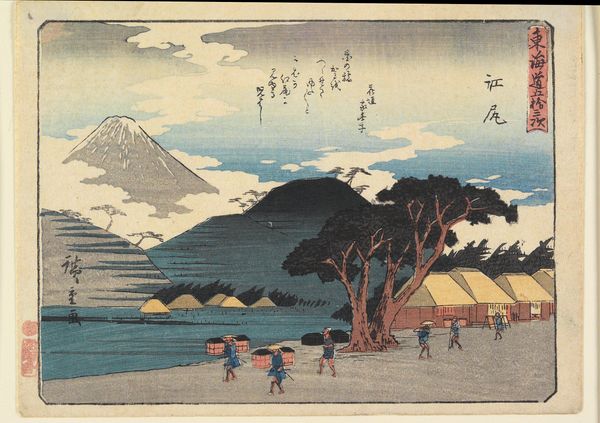

Dimensions: 6 9/16 x 9 1/16 in. (16.6 x 23 cm) (image)6 7/8 x 9 5/8 in. (17.4 x 24.4 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately, there's this stillness, almost a melancholic peace, in Hiroshige's woodblock print, "No. Okitsu," dating from 1847-1852. The colors are subdued, yet they create a vibrant landscape. Editor: Woodblock prints are deceiving in their simplicity. It's all too easy to ignore the complex labor process that produces what we're looking at, including the roles of the artist, the carver, and the printer. Curator: Exactly! It's crucial to acknowledge the historical and cultural significance of this piece within the context of Ukiyo-e art. These prints, originally mass-produced, reflected popular culture and the leisurely pursuits of the Edo period in Japan. They depicted scenes of everyday life and famous landmarks. Editor: That replication and commodification is precisely the point! These were not created as luxury objects, but they become precious commodities by virtue of art history institutions selecting, framing, preserving, and presenting them, changing both their physical being and their socio-economic role. Now it resides here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Curator: Indeed. I find it fascinating how Hiroshige captures a sense of distance. The way he renders the mountains in the background with this blurred, almost hazy quality draws us deeper into the landscape. There's this feeling of transition. Editor: And the composition itself invites scrutiny. Look closely. What appear to be stylized pine trees are adorned with what seem to be little white strips of papers. Also note that a person on the bottom left, leading a donkey. These are clues that tell us the land is inhabited, traversed. People use these roads. Labor shapes even what we understand as nature. Curator: That intersection of human life with natural splendor truly defines this piece. It underscores a spiritual connection with nature—very integral to Japanese culture. It really speaks volumes about society at the time, I think. Editor: These images were tools, enabling a whole rising merchant class to travel and claim social status. It gave the aspiring middle classes symbolic and sometimes material access to elevated levels of society and their privileges. It made the world feel simultaneously more knowable and more accessible, democratizing desire for all of those who consumed it. Curator: I agree, looking at "No. Okitsu" highlights not just the artist's skill but how the print played a role in wider Japanese society at the time, mirroring and perhaps shaping its values. Editor: And it is a sharp reminder that what we see is also shaped by all the choices--conscious and unconscious--that made the print, the act of preserving the print, and the decision to present this print to us today, in just this way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.