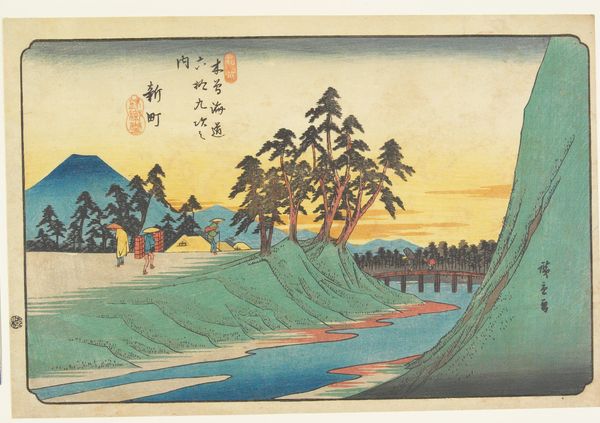

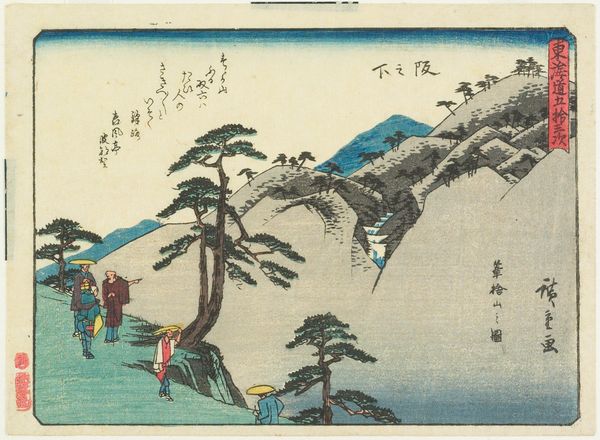

print, plein-air, ink, woodblock-print

#

water colours

# print

#

plein-air

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

woodblock-print

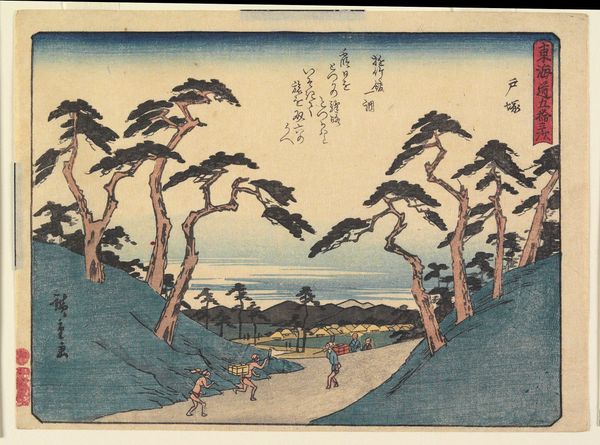

Dimensions: 8 7/8 × 13 7/8 in. (22.5 × 35.3 cm) (image, horizontal ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at Utagawa Hiroshige’s “No. 12,” created sometime between 1835 and 1838, one is immediately struck by its serenity, isn’t it? The palette is gentle and welcoming. Editor: Yes, "serenity" captures it well. But to me, there is something more layered than simply serenity here. Those figures trudging along the shoreline seem almost burdened, highlighting labor's toll against a backdrop of what you called a 'gentle palette.' What is it suggesting? Curator: I think it invites consideration of Edo-period Japan through the lens of its artistic conventions, popular culture, and social practices. Hiroshige became a prominent Ukiyo-e printmaker, didn’t he? "No. 12" features many natural, serene qualities often present in the art of his time. We get this from the presence of the river, mountains, and plantlife. The laboring individuals you describe were an inescapable part of reality during that period. Editor: Indeed, it's a brilliant encapsulation of Ukiyo-e aesthetics, which at that time democratized art with affordable woodblock prints, thus mirroring socio-political tensions. Beyond mere escapism through depictions of nature or fleeting pleasure, what positionality do you think everyday people held when accessing art through artworks like this? Curator: This is a great entry point when examining these works! Think about the commercialization of landscapes, not only catering to domestic audiences, but to Western fascination with exoticism and imagined authenticity, and the ways Hiroshige’s views may well have shaped how both Japanese people viewed their own world. This landscape tradition is fascinating as we examine a sense of idealized beauty with those workers quietly embedded as integral actors on this idyllic stage. Editor: You're highlighting how prints like these constructed both local and global identities. Yet the artist's biography complicates the idea that his aesthetic stands outside of a system of marginalization; as a member of the samurai class who gave up his status and inheritance, his images, in my eyes, provide commentary on class. The workers may be background characters, yet the fact that they are visible means that their lives, though arduous, are significant. What did it mean to make that visible through mass media? Curator: Right, this opens the door to deeper explorations of commodification and class anxieties in art and life! Appreciate you bringing up that complex layer, how Hiroshige’s compositions and output raise questions on how everyday lives—and their inherent contradictions—get not just shown but sold and consumed. It invites a complex reckoning! Editor: And I think a vital, contemporary lens! Hopefully, it prompts further discourse from listeners, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.