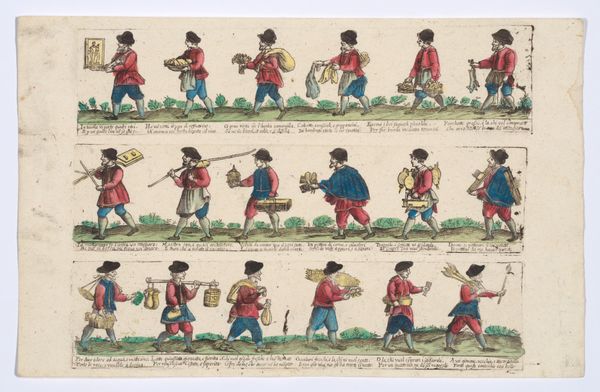

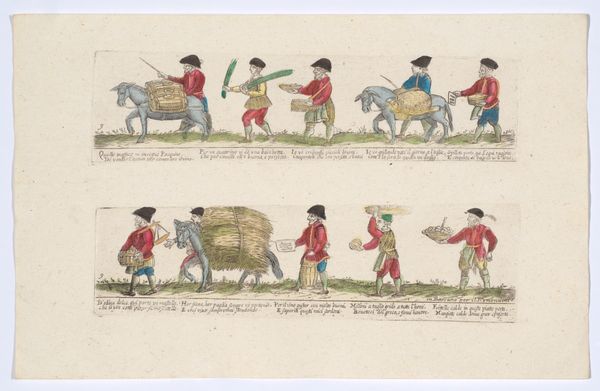

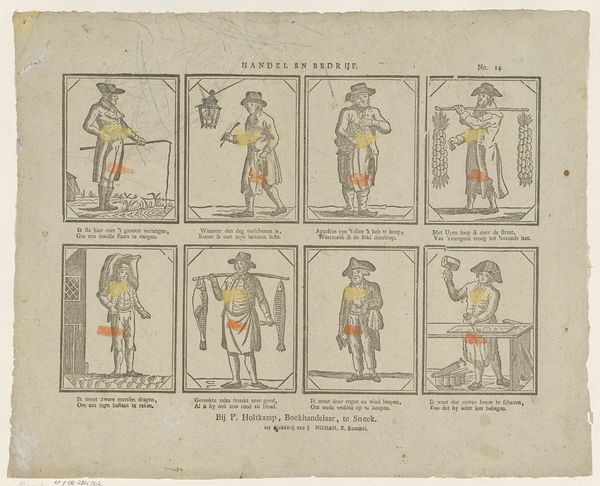

Title and plate 1 depicting the cries (trades) of Rome, here including vendors of goldfish, Milanese swords, hats etc, from the 'Descrición de las artes que se llaman para los calles de la ciudad de Roma' 1765 - 1805

0:00

0:00

drawing, coloured-pencil, print

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

# print

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 5/8 × 15 1/16 in. (24.5 × 38.3 cm) Plate (Top): 1 15/16 × 11 5/8 in. (5 × 29.5 cm) Plate (Middle): 2 15/16 × 11 15/16 in. (7.5 × 30.3 cm) Plate (Bottom): 2 3/4 × 12 in. (7 × 30.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

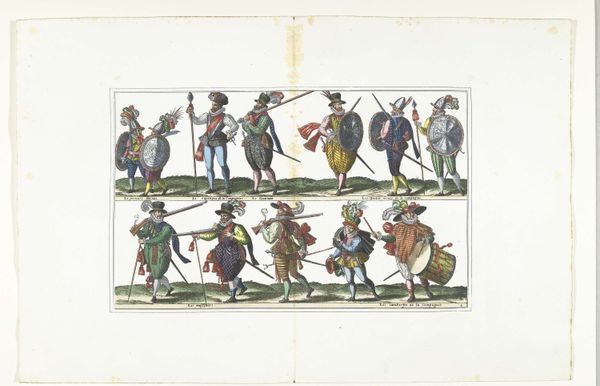

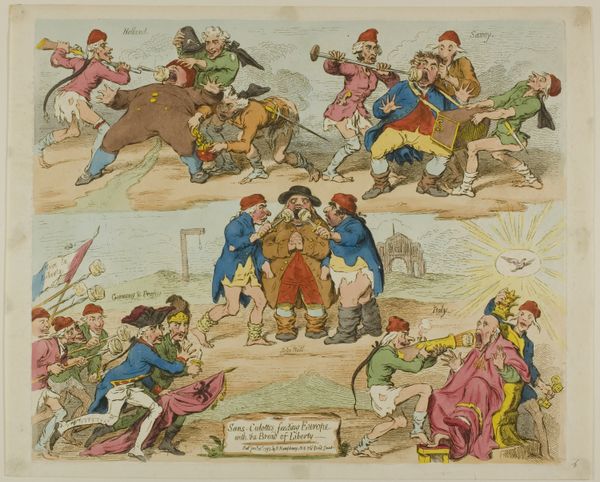

Editor: So, this is "Title and plate 1 depicting the cries (trades) of Rome," from between 1765 and 1805, attributed to Remondini. It's a colored-pencil drawing and print. What I immediately notice is how it seems to document the daily life and labor of ordinary Romans. What strikes you most about it? Curator: I'm interested in how this print elevates the everyday activities of street vendors into a subject worthy of artistic representation. The very act of documenting and categorizing these trades speaks volumes about the changing social structures and the rise of a merchant class in Rome during this period. Editor: Could you expand on that? Curator: Well, think about the materials used. Colored pencil and printmaking were increasingly accessible means of production. They allowed for the dissemination of images, impacting how these trades were perceived. Were these artisans elevated or were they perhaps subtly being othered as a commercial transaction? How would it have been viewed in contrast with work produced in say marble or other pricier materials. Editor: That's fascinating! It challenges the traditional hierarchy between fine art and what we might consider commercial imagery. Curator: Exactly! By focusing on the 'cries'—the actual sounds of the marketplace—the artist directs our attention to the lived experience of economic exchange. It brings it all down to earth through sound, like field recording might do now. Editor: This makes me see the print not just as a historical record, but as a comment on the burgeoning economy and social changes within Rome at the time. Curator: And it really pushes the boundaries of where the “art” of the Italian Renaissance could be seen as dwelling. We get it in print form by looking at people working in an early economy. That labor is now venerated within museum spaces. It has a new social utility and arguably a brand-new meaning as a museum artifact. Editor: Thank you; that shift in perspective really sheds new light on how I view this piece. I now understand this representation not as something precious but, rather, a commentary on consumption that informs a specific moment in time. Curator: Yes, exactly. Understanding the modes of production helps unpack the artistic and social ambitions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.