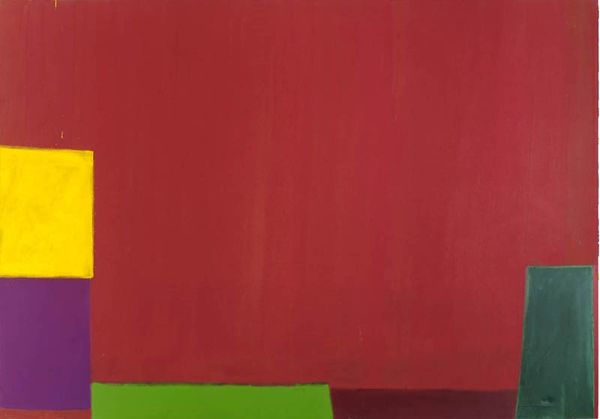

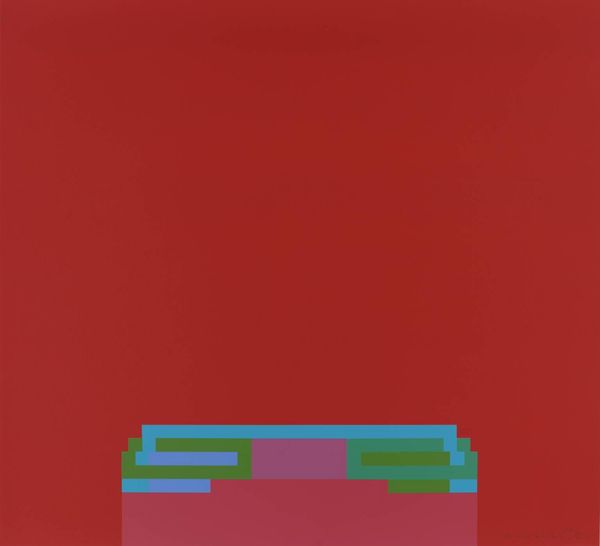

Dimensions: support: 2035 x 2030 mm

Copyright: © Paul Huxley | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

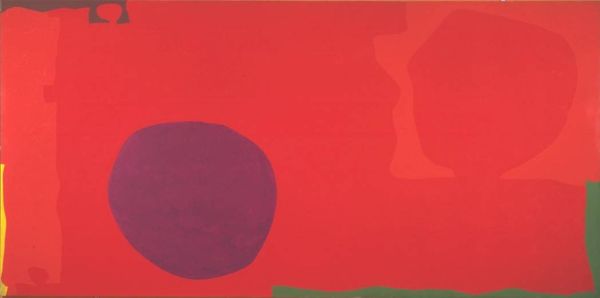

Editor: Here we have Paul Huxley's *Untitled No. 44* from the Tate Collections. The contrasting colors are bold, but I am unsure how to interpret the floating shapes. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Well, its minimalist approach evokes a sense of postwar abstraction, but what does the relationship between the shapes and the background tell us about the artist's intentions? Are they bodies, or some kind of symbol? Editor: I didn’t even think of that. Perhaps it’s Huxley’s comment on the lack of representation of certain bodies in art? Curator: Precisely. By decentering traditional forms and embracing abstraction, Huxley subtly challenges conventional notions of representation and invites us to reconsider whose stories are told in art. Editor: That’s a great point. I will be sure to look at other abstract art with this in mind.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

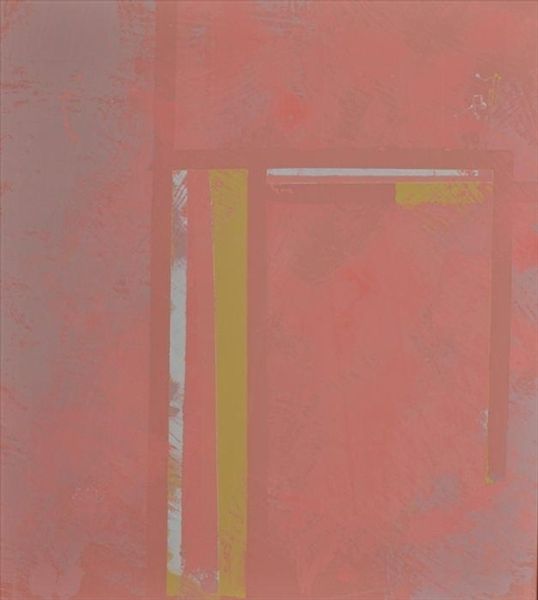

Untitled No.44 is a large painting in acrylic paint on canvas. Over a thinly applied layer of pink paint, a sequence of more saturated dark green painted shapes are arranged, as if flowing down from the top right hand corner, part way down the right edge of the painting and then, as a series of three droplets, pooling and extending diagonally down towards the lower left hand corner of the painting. These green shapes appear to flow over and across the pink ground and yet this implied movement over recessive space is denied by the material facts of the way in which the paint is applied to the canvas in flat areas of colour: cold-toned green against the warm-toned pink. Nevertheless, from the arrangement of the green areas as particular shapes that seem to flow diagonally across the painting, the downward pull of gravity is also implied within a perspectival space. It is thus difficult not to read the abstract nature of this painting in an associative way. Ultimately, as the critic David Thompson described in 1964: