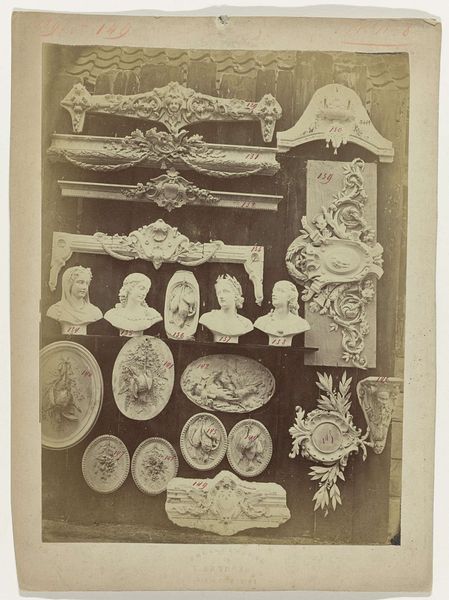

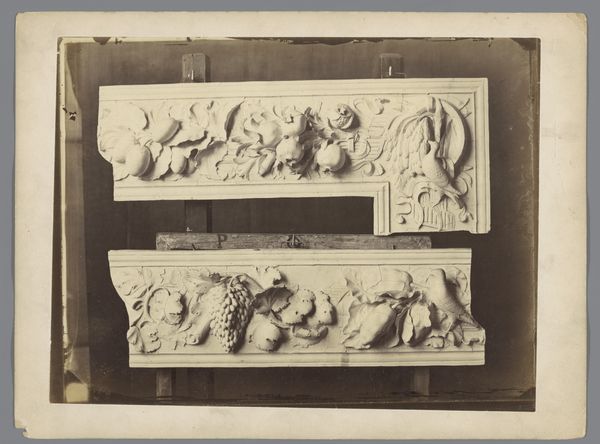

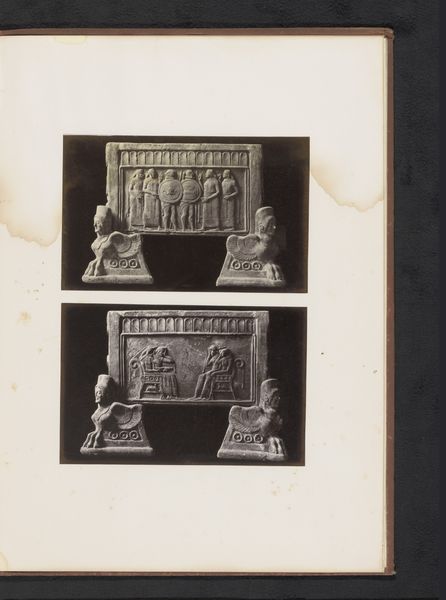

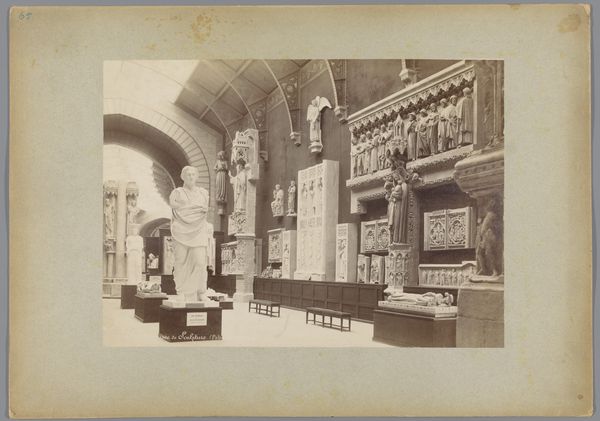

Fragmenten van Etruskische ornamenten en reliëfs in het Museo Kircheriano te Rome, Italië 1857 - 1875

0:00

0:00

jamesanderson

Rijksmuseum

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

muted colour palette

#

photography

#

old-timey

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

19th century

#

academic-art

#

decorative-art

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 202 mm, width 259 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

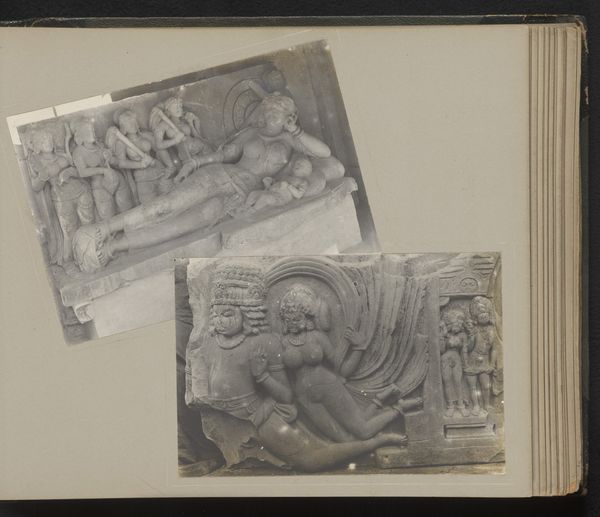

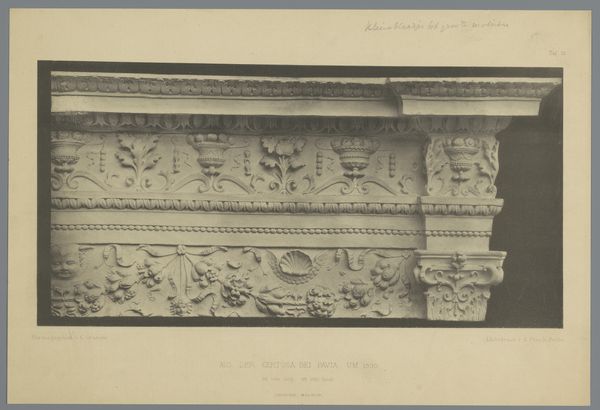

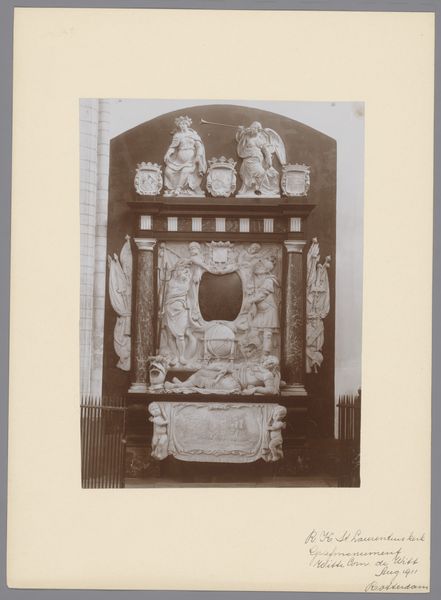

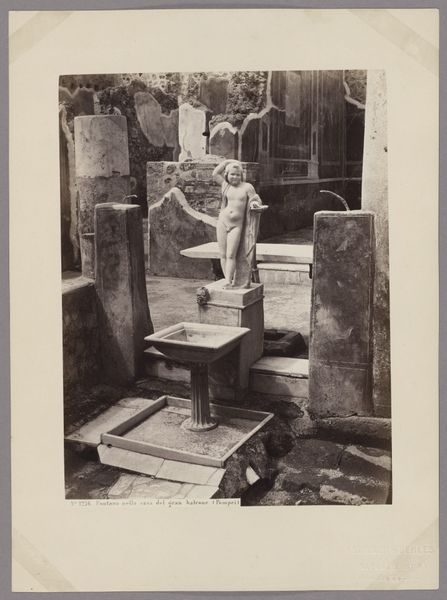

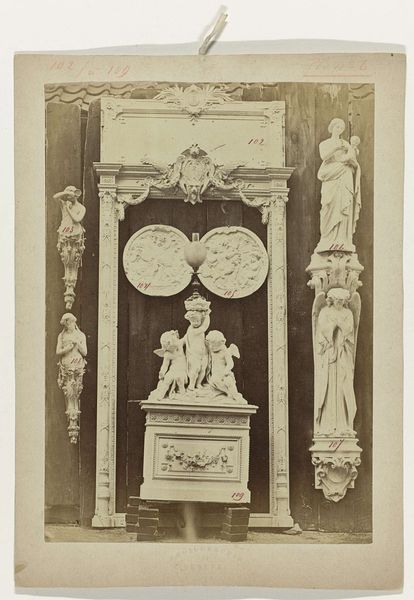

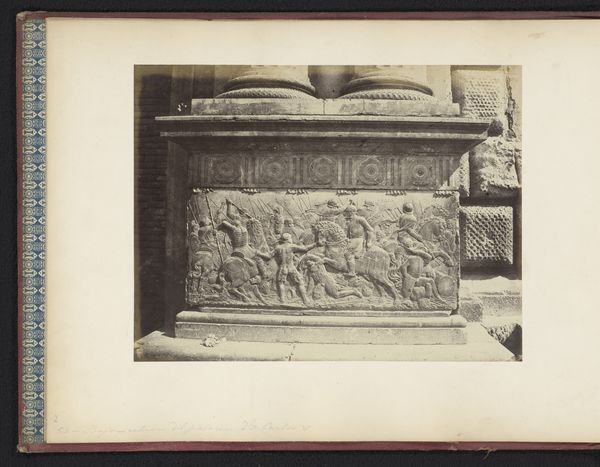

Curator: What strikes me first is how these fractured Etruscan fragments, remnants of what was, evoke a quietude, almost a stillness, despite being caught mid-narrative, mid-expression. Editor: It's definitely a careful staging of material culture, this photograph from sometime between 1857 and 1875 by James Anderson. The Rijksmuseum holds it, a sepia-toned albumen print of fragments housed at the Museo Kircheriano in Rome. Makes you wonder about the process of excavation, display, and then photographic reproduction – labor at every level. Curator: Absolutely. Think of each shard carrying its lost world – rituals, myths, daily lives, solidified in clay, in stone. I’m imagining the hands that sculpted these friezes, reliefs… were they whispering secrets into the material as they worked? And this warm toned photograph now presents them almost like sacred relics, catalogued and preserved under glass. Editor: But see how Anderson emphasizes their fragmentary nature? It isn't just about celebrating the past but almost about owning it, classifying it within the scientific, almost clinical eye of the 19th century. Albumen printing involved coating paper with egg whites—a protein binder—sensitized to light, and look at that soft texture—a world away from today’s slick digital prints. The albumen itself, of course, is also a record of labor, the breaking of eggs, a mass produced object itself and one consumed to nourish labor. Curator: Fascinating! I love thinking about how art becomes archaeology, archaeology becomes data, and data…becomes, once again, art. You begin to think of the fragments less as ruins and more as whispers – each a word in a story that refuses to be completely silenced. Editor: Right! It’s not so much about what’s depicted on these ornamentals, but more about how the depiction itself—the method, the choices—reveals so much about Anderson's era, about modes of collecting, displaying, preserving, and disseminating visual culture, and therefore ideology. Curator: Looking at the faded sepia tones...it is the very transience, the vulnerability of existence, speaking to us now, echoing through time. Editor: It’s a fascinating meditation on time, isn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.