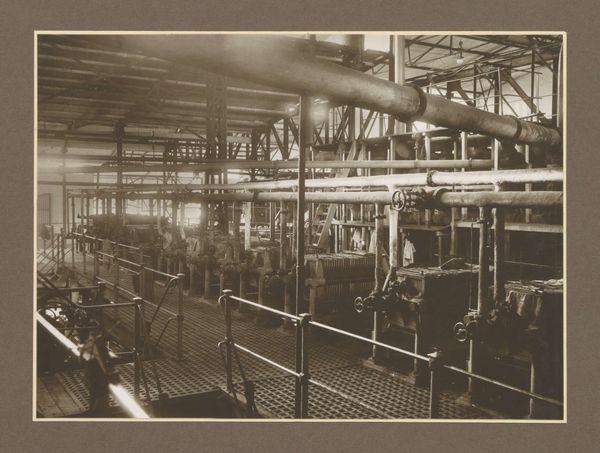

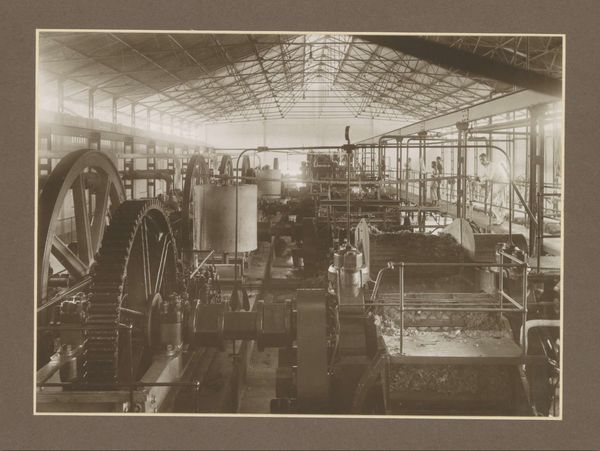

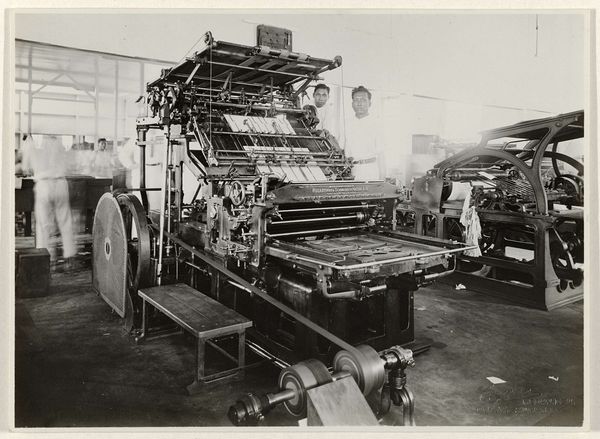

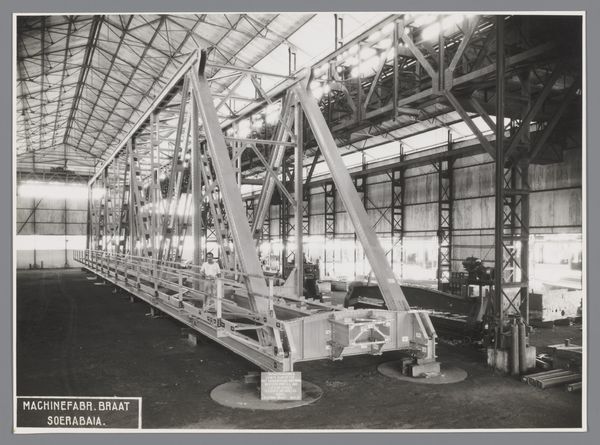

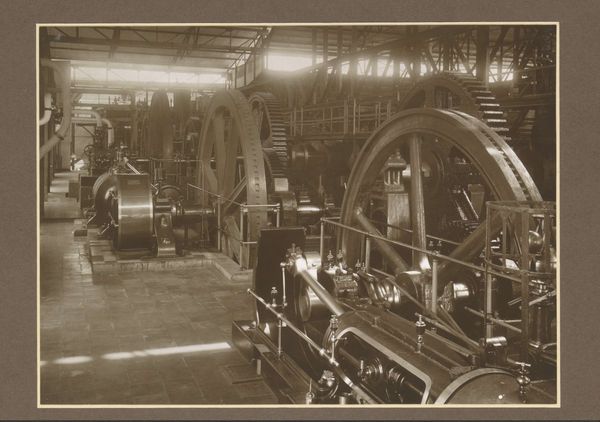

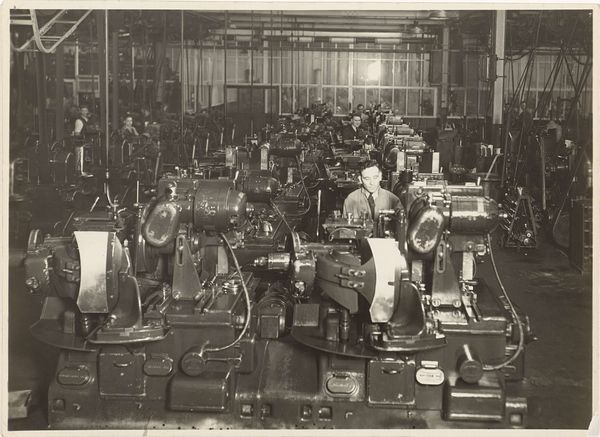

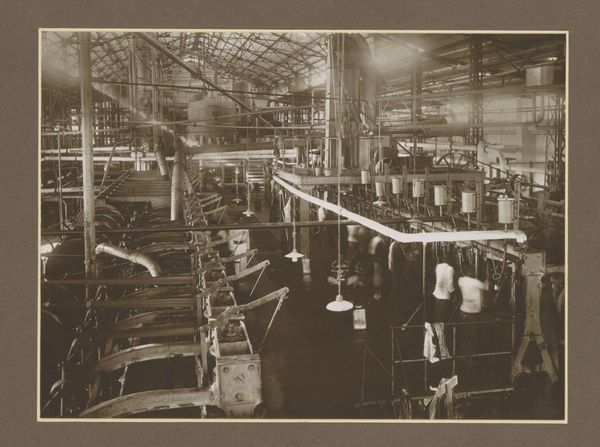

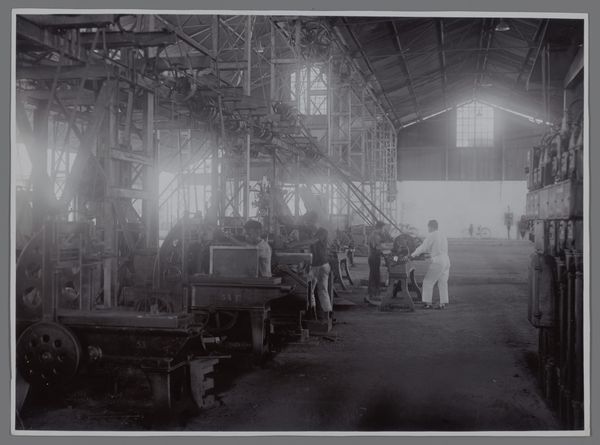

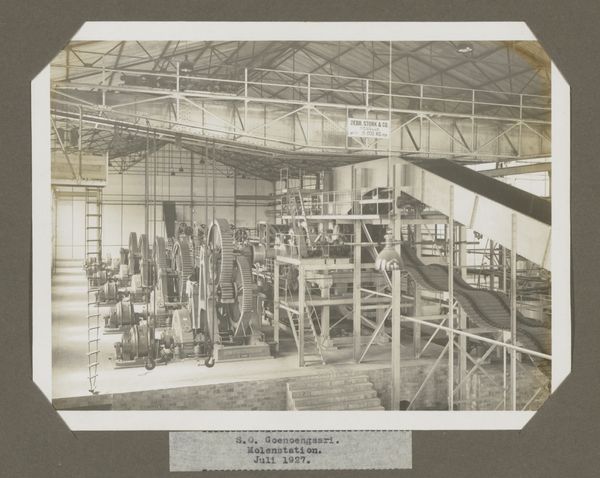

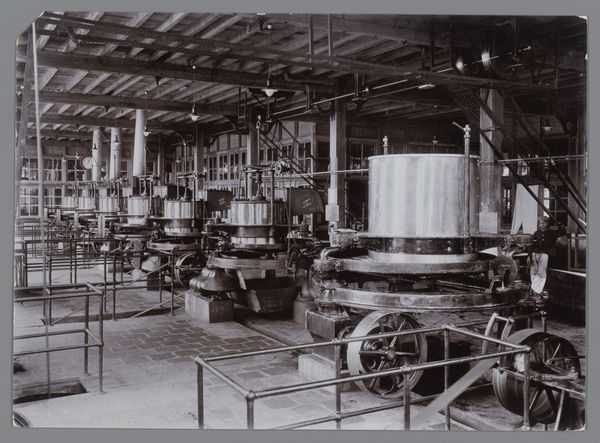

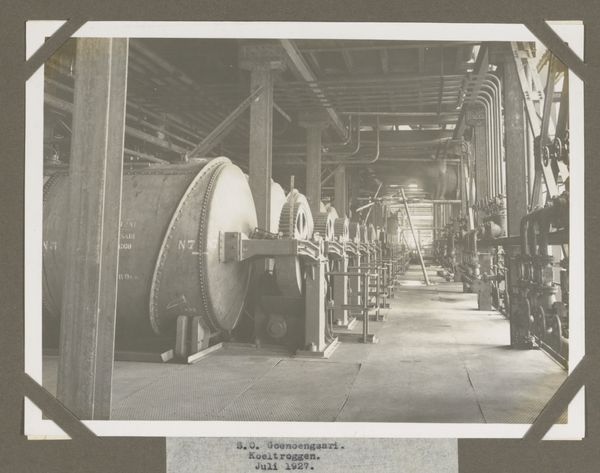

Interieur van de fabriek op de suikeronderneming Nieuw Tersana, Cheribon, voormalig Nederlands-Indië c. 1890 - 1911

0:00

0:00

photography

#

still-life-photography

#

black and white photography

#

dutch-golden-age

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 168 mm, width 226 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This photograph, "Interieur van de fabriek op de suikeronderneming Nieuw Tersana, Cheribon, voormalig Nederlands-Indië" was taken by Onnes Kurkdjian sometime between 1890 and 1911. It’s a monochrome image, dominated by this massive piece of industrial machinery. It has a stark and imposing feel to it. What’s your take on it? Curator: This image speaks volumes about the socio-political context of its time. Beyond the purely technical record of industrial processes, it subtly highlights the brutal realities of colonial economies. The subdued presence of the laborers almost disappears amidst this machine. Can you consider what their lived experience would have been? Editor: It’s easy to overlook the human element. You are right, there are figures near the machine who seem dwarfed and almost consumed by the machinery. Curator: Exactly. This is more than a factory interior; it's a document of power dynamics. The sugar industry in the Dutch East Indies relied on exploitation and the subjugation of the indigenous population. How does seeing those workers shift your interpretation of the photograph as a whole? Editor: I now see how the photograph portrays power through the factory's architecture itself and highlights the exploitation of local labour and resources for western interests. What did sugar production signify during that period? Curator: Sugar production meant wealth and colonial expansion. The image serves as a visual text revealing the mechanics of wealth extraction and the dehumanization inherent within. This goes further than documenting a factory - the photo questions economic systems and structural injustice. Editor: I hadn't considered the broader implications of what it meant. This photograph presents a new perspective to consider about economic colonial exploitation. Curator: Precisely. It encourages us to interrogate the connections between aesthetics, industry, and the hidden costs of progress.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.