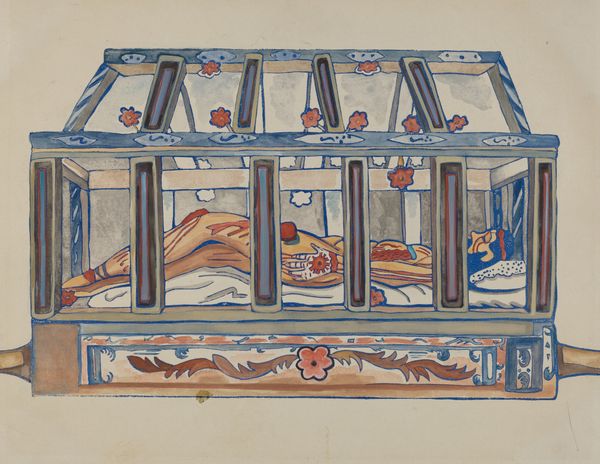

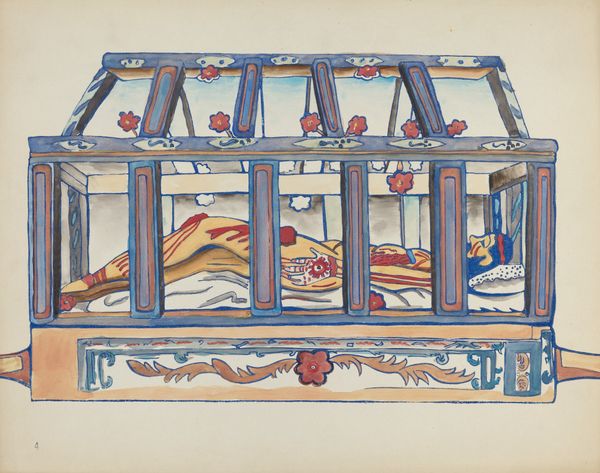

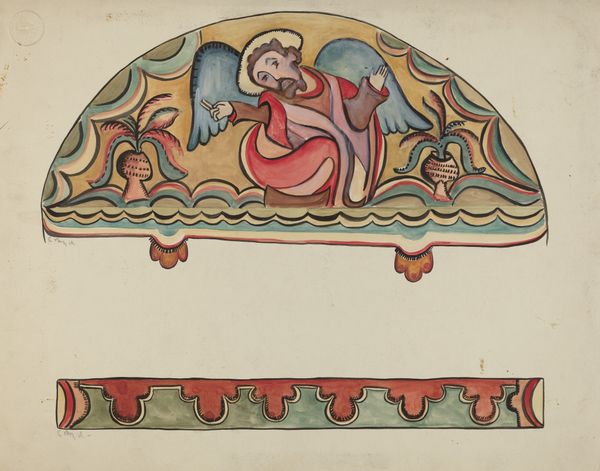

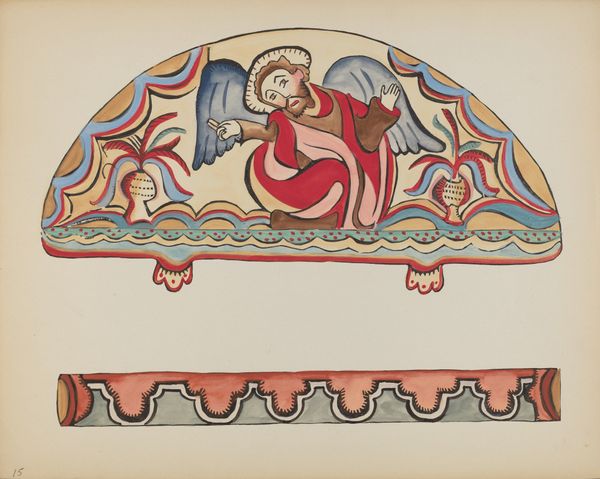

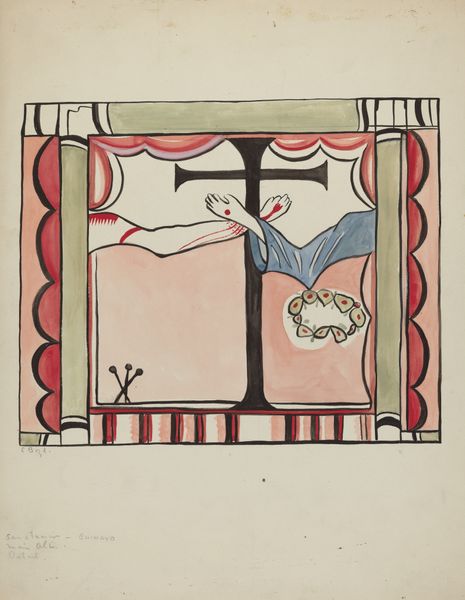

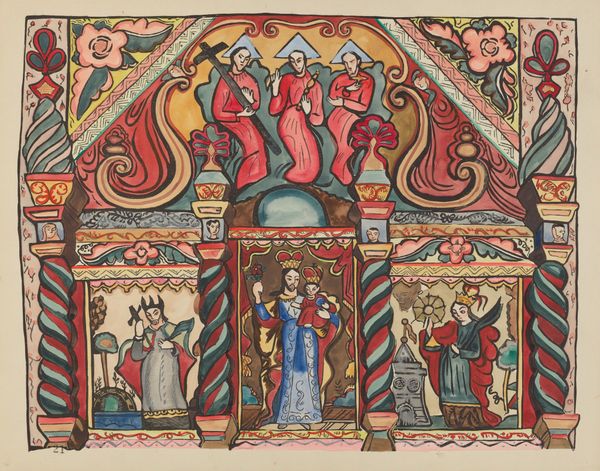

drawing, tempera, watercolor

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

genre-painting

#

modernism

#

miniature

Dimensions: overall: 29.7 x 36.7 cm (11 11/16 x 14 7/16 in.) Original IAD Object: none given

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Here we have E. Boyd’s "Christ in Sepulchre," dating from sometime between 1935 and 1942. It’s a small work, executed in watercolor and tempera, with details added in colored pencil. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It’s unsettling, yet delicate. The miniature scale and decorative box contrast sharply with the violence implied by the wounds. There’s a dissonance that’s quite arresting. Curator: Indeed. The craftsmanship itself is rather intriguing. Boyd, while celebrated as a curator and historian, consistently engaged with various media and processes throughout their career. We must remember the broader context of craft movements during that time and consider Boyd's intimate knowledge and personal experience with different means of production as critical to this work. Editor: Precisely. This piece feels heavy with its historical weight. Consider how images of Christ’s suffering have been weaponized throughout history, especially in the context of colonial violence in the Americas. Boyd’s identity as a woman, working within a patriarchal religious framework and living in a region grappling with complex colonial legacies—all of these elements contribute to a fascinating tension in the work. The open wounds, the somewhat constrained body... Curator: Speaking of the body, look at the coloration. The ochre tones create a sense of raw physicality that’s softened, almost veiled, by the watercolor washes. Notice how the decorative box frames Christ, placing the scene in an intriguing relationship to both folk-art traditions and the conventions of religious iconography. Editor: And the stylization itself! The miniature recalls retablo traditions, devotional paintings on tin. How might Boyd's choices reflect an effort to reclaim or subvert certain established meanings through form? Does this intimacy offer a way to mourn collectively but resist an easy resolution? Curator: Perhaps. We could interpret Boyd’s approach to materials – humble materials, really – as a democratization of religious imagery. It makes the subject less exalted and therefore more available. Editor: I see that. This invites us to ponder on power dynamics at play: the colonial implications and then what those might say about gender and religious authority as filtered through the maker’s own identity and place. Curator: Considering it all together, I would say Boyd asks us to actively engage with familiar narratives and reconsider their lasting effects. Editor: A powerful and thought-provoking testament, delivered through what appears to be such fragile beauty.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.