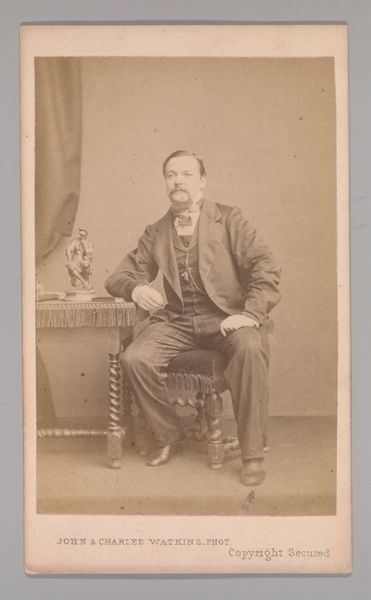

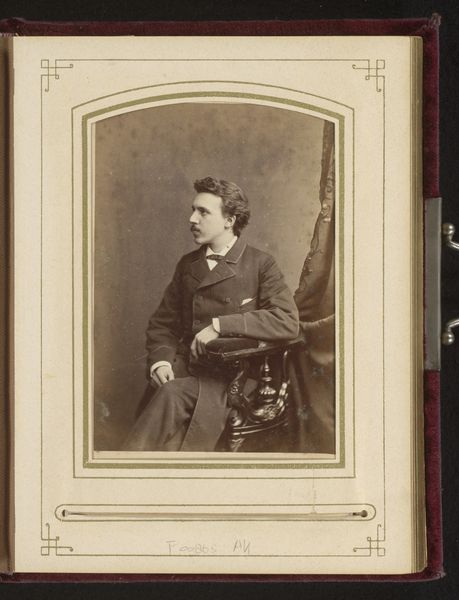

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

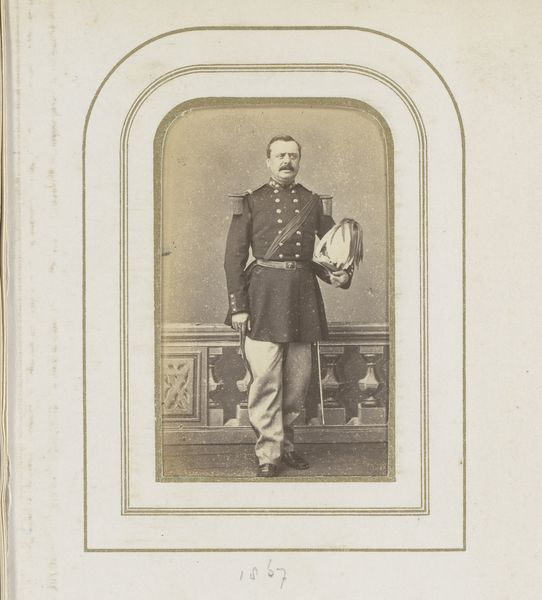

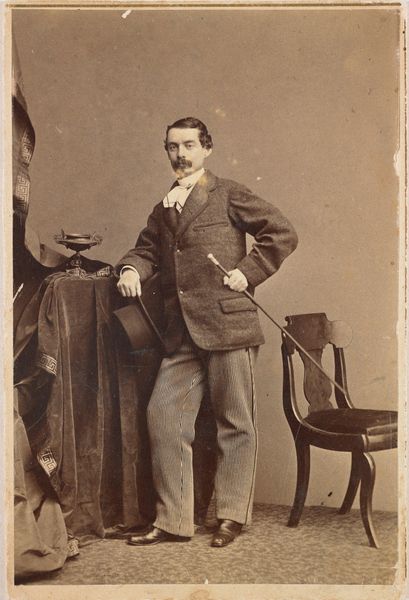

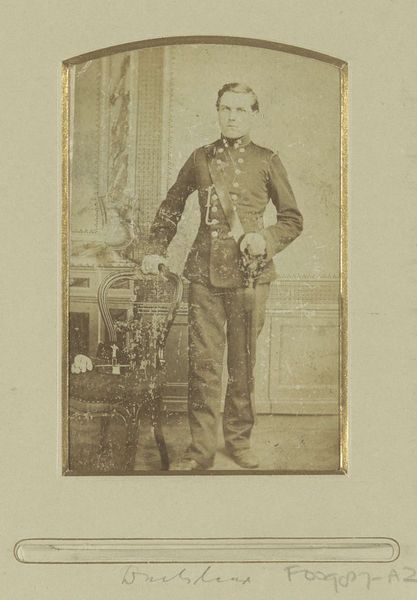

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this daguerreotype, titled “Portret van A. W. Rueck,” created sometime between 1858 and 1867 by Henri Pronk. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It has an interesting mood. There is a stillness but also an assertiveness, I am drawn to the detail in the buttons and especially to the fringe on his epaulets and stool. It speaks volumes about the time and, I’d wager, about Rueck himself. Curator: It certainly captures a specific historical moment. Consider the socio-political backdrop against which this portrait was produced. Photography was increasingly accessible, reshaping how individuals and institutions crafted and controlled public image. How does this contribute to the way this photo operates? Editor: Mass production changed photography. The daguerreotype democratized portraiture to some extent, moving from painting, but there were still costs associated with having your photograph taken and producing prints. So access wasn't equal. Also, thinking about how light works with the silvered copper plate – it’s almost like alchemy in the studio, quite a different skill than portrait painting. Curator: Precisely! It's not simply about replicating reality, it's about performing social identity. The studio setting, the draped curtain, and books staged next to him contribute to a carefully cultivated representation. Editor: All that is certainly *staged* but the long exposure required probably contributes to the serious, unsmiling demeanor of the subject. This affects how it’s perceived now, of course. If it had been faster, the social conventions of photographic portraiture may have led to a less somber expression. Curator: I see that. It reflects a complex interplay between technological constraints and emerging cultural norms around photography. We cannot overlook the image’s relationship with institutions such as family, state, and museum archives. They each affect its meanings. Editor: Absolutely. We see how photographic technology was enmeshed with economic status and social structures – all tangible aspects which shaped not only its making but also its continuing life in archives. Thinking about all of this alters one's experience of simply “seeing” this historical portrait. Curator: It certainly does shift how we perceive this image today. Editor: Indeed. Thanks for pointing all of this out.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.