daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

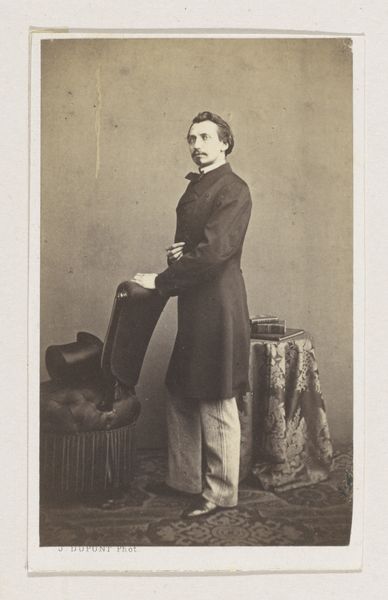

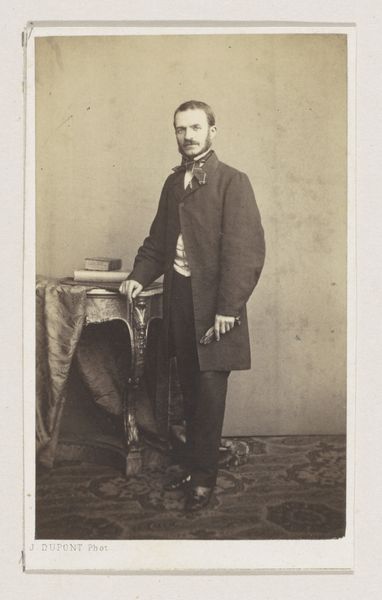

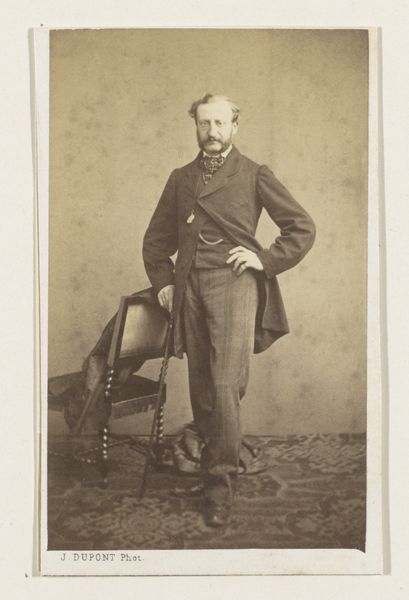

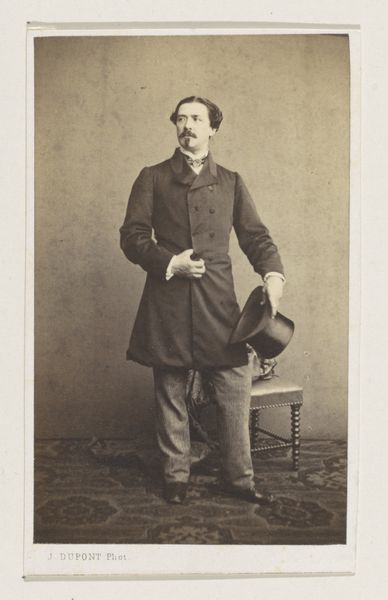

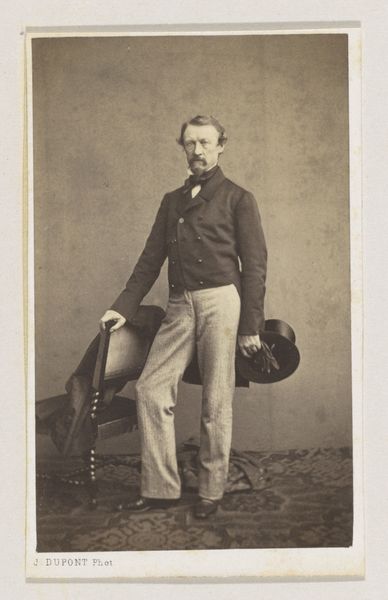

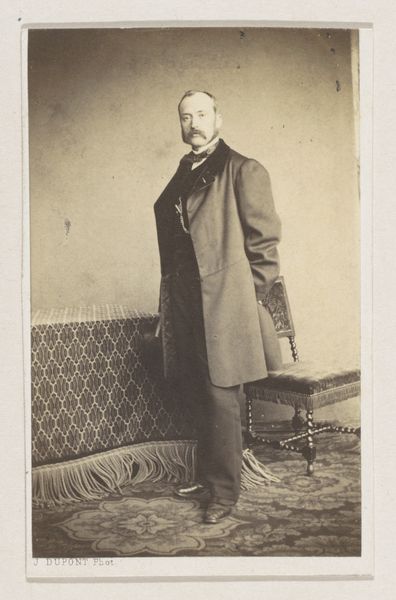

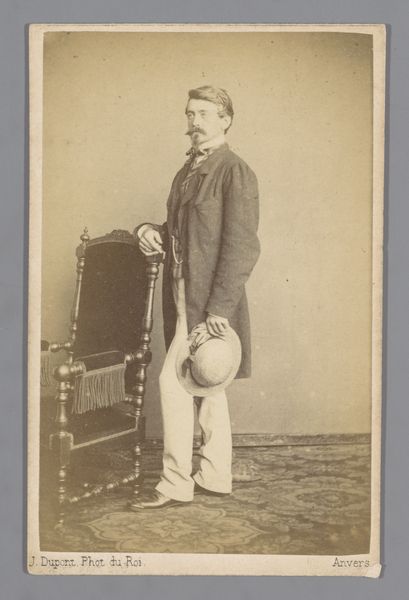

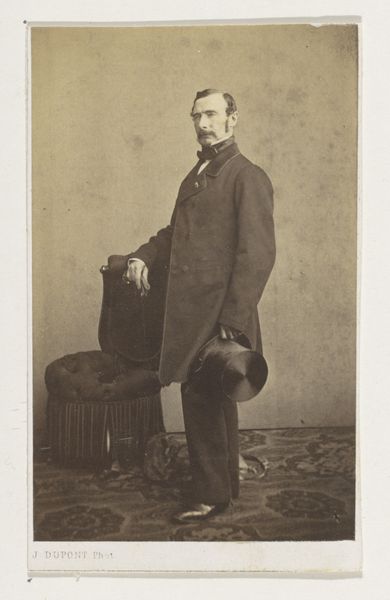

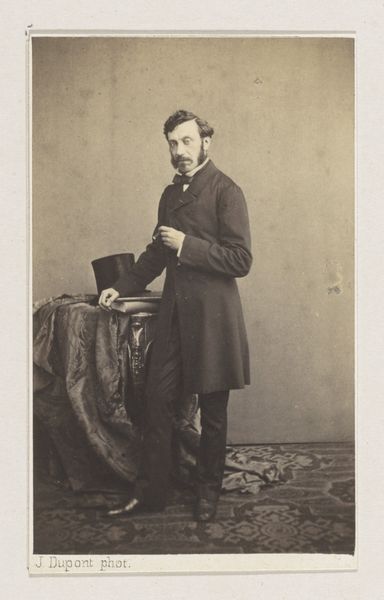

Curator: This striking daguerreotype from 1861 is titled “Portret van de schilder Ferdinand Wilhelm Pauwels, ten voeten uit,” and it's attributed to Joseph Dupont. My immediate reaction is one of restrained dignity; the subdued sepia tones lend the image a gravitas that reflects, perhaps, the subject’s artistic status and societal position. Editor: Dignity, yes, but also perhaps a reflection of the constraints of early photography. This isn’t a casual snapshot. The stiff pose, the meticulous detail in his patterned pants – they all speak to a performance of identity as much as a portrayal of the man himself. There’s something inherently political in deciding how you present yourself to the relatively new medium of the camera. Curator: Absolutely. Studio portraiture in the mid-19th century was about constructing an image of oneself for posterity. Ferdinand Pauwels, a successful painter of historical scenes, would have been acutely aware of how he wished to be perceived. Note his tailored coat, the carefully knotted tie – these are signifiers of bourgeois respectability, designed to cement his position within the art establishment. The chair on which he leans provides an additional element of status, indicating wealth and access to luxury. Editor: It also subtly positions the subject in a passive, almost staged manner. His gaze isn't directly at the viewer, instead he's glancing towards the right of the camera frame, contributing to the artificial atmosphere. I’m interested in how photographic portraits like this, in their staged reality, contrast to painting’s claim to capturing authentic expressions, specifically those painted during the same period. Curator: Indeed. Photography complicated the notions of artistic realism. Pauwels’ artistic training was rooted in Academic Art and realism movements, so perhaps his willingness to embrace photography as a mode of representation speaks to photography’s growing validation at that time. Editor: I think it's safe to suggest there is power to having a visual likeness of yourself distributed at this time. This image creates access, particularly as photography democratizes image production. Considering his background and historical context, the portrait isn't just a visual representation; it's a calculated assertion of identity, class, and artistic standing that enters the social fabric and leaves its mark in the visual history of the era. Curator: It’s an image that encapsulates so much about the relationship between art, society, and representation at a pivotal moment in history. Editor: An early engagement with the now all too familiar dynamics between seeing, being seen, and wanting to be seen in particular ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.