Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

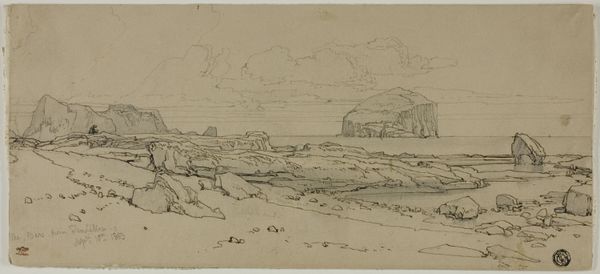

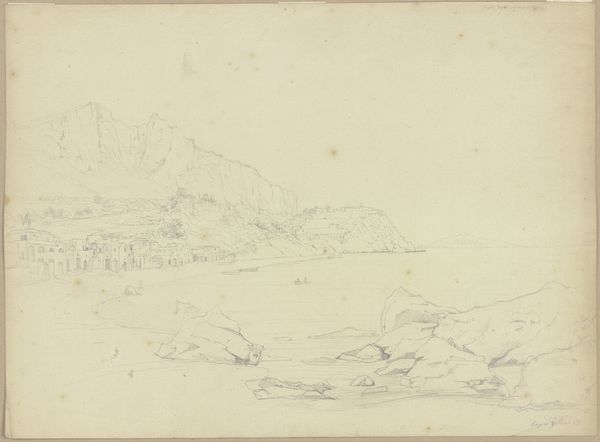

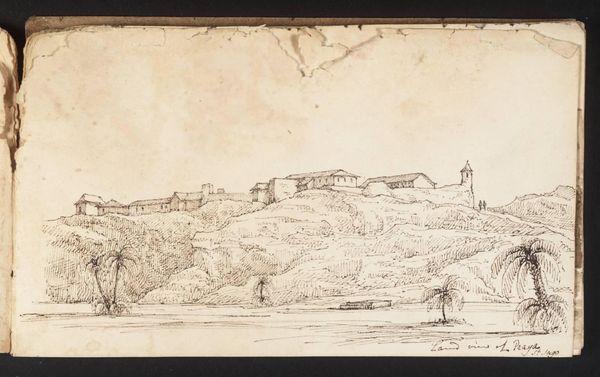

Curator: Let’s consider Tavenraat’s “Mountain Landscape with a Castle Ruin on a Lake,” drawn in 1859, using only pencil. Editor: Yes, it’s striking how he captures this sort of sweeping landscape with such simple materials. It almost feels like a study or sketch rather than a finished piece. How do you interpret this work, especially given the period it was created in? Curator: I find myself focusing on the pencil itself. It’s a relatively inexpensive material, industrially produced. This democratisation of art supplies allowed more people to engage in landscape drawing. Do you think the choice of such a commonplace medium alters how we understand the artist's perspective on nature? Editor: That’s a really interesting point. It almost flattens the Romantic ideal of the sublime. If anyone could theoretically create this image, does it change its value or meaning? Curator: Precisely. Furthermore, the landscape itself—observe the ruined castle. What once symbolized power is now in decay. Pencil, mass production, and a fallen structure – a reflection on shifting social and material conditions of the time? How do you think industrialization and consumerism played a role in this shift? Editor: I guess there's a sense of making even grand themes and subjects like historical power structures accessible, reproducible, perhaps even disposable? Curator: Indeed! The pencil marks are traces of labor, reminding us that even Romantic landscapes are the product of material processes and economic realities. Anything strike you particularly about that concept? Editor: I suppose that examining these landscape images with materialist eyes can encourage conversations on class and labour instead of traditional narratives of individual inspiration. Thanks! Curator: Exactly. It invites a more comprehensive reflection. Considering these sketches are a product of a specific time and the tools and techniques employed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.