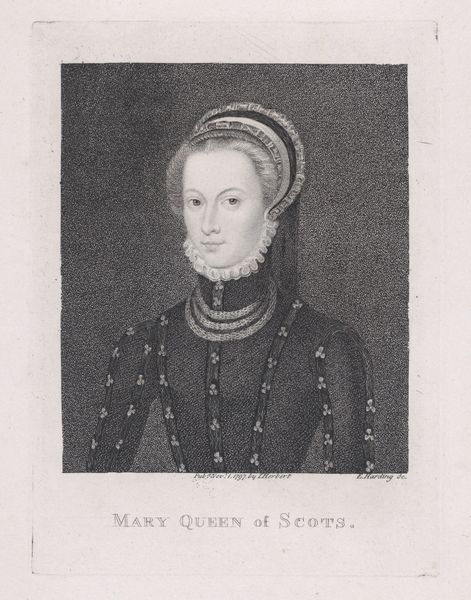

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

personal sketchbook

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 5 5/16 × 3 7/8 in. (13.5 × 9.9 cm) Sheet: 6 15/16 × 4 1/2 in. (17.6 × 11.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have an 18th-century engraving by Isaac Taylor I, entitled "Mary, Queen of Scots," currently housed at the Met. There's an incredible stillness about this portrait; she seems so contained. What symbols or messages do you perceive in this work? Curator: Well, the oval frame itself is immediately symbolic. In portraits, the oval often suggests an idealized or timeless quality, a way of framing a memory rather than capturing a fleeting moment. Think about what Mary represented then, and what she represents now. Editor: A martyr, perhaps? A tragic figure in history? Curator: Precisely! And look at the detail in her clothing. The intricate patterns, almost like interwoven knots. Consider the symbolic weight of knots – binding, connection, but also constraint. Does her ornate dress feel like adornment, or like a gilded cage? The cultural memory associated with Mary is thick with constraint and ultimate imprisonment. Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t thought about the clothing that way, more as a sign of her royal status. Curator: It's both, of course. Clothing has always communicated status, but the *specific* details tell us more. Also, notice how her gaze is direct, but slightly downward. She’s acknowledging the viewer, but perhaps with a hint of humility, or even resignation. Do you see it? Editor: I do. There is a melancholy to her expression that reinforces the idea of her as a figure trapped by fate. It seems intentional, creating an overall sense of the burdens and expectations of royalty in that period. Curator: Indeed, and it’s precisely that tension between outward display and inner emotion that makes the engraving so compelling, even centuries later. Editor: Thank you. I will definitely carry those notions of memory and visual symbolism with me. Curator: And hopefully consider how we project our own understandings onto historical figures. Always consider your position in time when interpreting older art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.