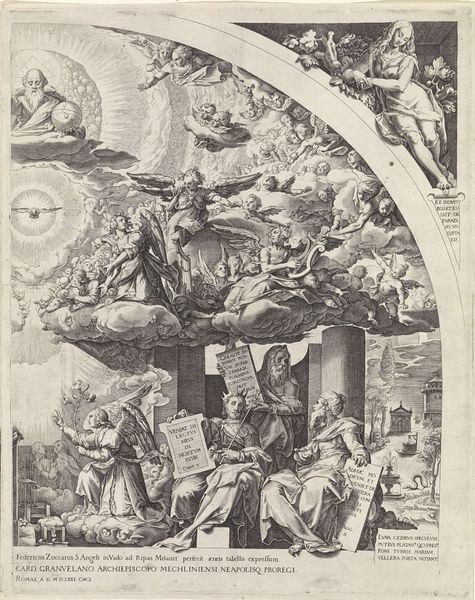

Johannes ziet het Nieuwe Jeruzalem: 'en het eeuwig leven, amen' 1579

0:00

0:00

johannsadeleri

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

allegory

# print

#

landscape

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 213 mm, width 243 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

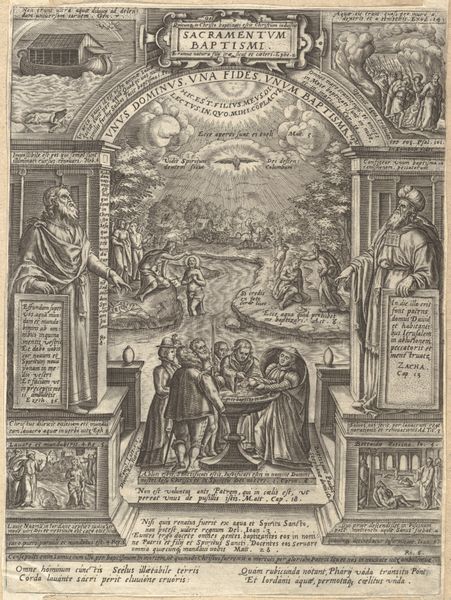

Curator: This print, “Johannes ziet het Nieuwe Jeruzalem: 'en het eeuwig leven, amen',” was created in 1579 by Johann Sadeler I. It’s currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is of an elaborate stage set. The meticulous details are astonishing, a tiny, bustling city emerging from ethereal clouds. It's as if we're being granted privileged access to a divine revelation. Curator: As a print, specifically an engraving, the work would have necessitated a deep understanding of metallurgy, tool-making, and the properties of the paper used to carry the image. The act of producing multiple identical images points towards a desire to disseminate the imagery far beyond the typical sphere of painting for a wealthy patron. Editor: Right, it’s interesting how this allows the image to function almost as religious propaganda, accessible across geographical and social strata. Look at the careful articulation of the architecture in contrast to the stylized rendition of figures. How does the visual language support the themes of promise and hope? Curator: The image directly relates to social conditions. As a Northern Renaissance print, it would be viewed in domestic settings and perhaps function almost like a biblical affirmation of wealth coming from on high to those deserving of eternal life. The very availability of such intricate prints for private viewing transformed personal relationships to religious imagery. Editor: Precisely. Note how the scale is played with: We've got a God-like figure looking down from the heavens along with Saint John on the rocky shore. Yet, the focus draws toward that centralized metropolis beyond our world. How might viewers in the 16th century have related to it socially or politically? Curator: We must examine the print as an artifact produced, consumed, and ultimately valued within a specific set of socio-economic relations. The labour, the technology and skills required point us to questions around religious authority, and individual salvation as related to moral industriousness. Editor: Ultimately, I’m struck by its capacity to present what is literally the stuff of dreams. This engraving, mass produced yet intricate in its detail, transports us into a visualized and material imagining of everlasting life.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.