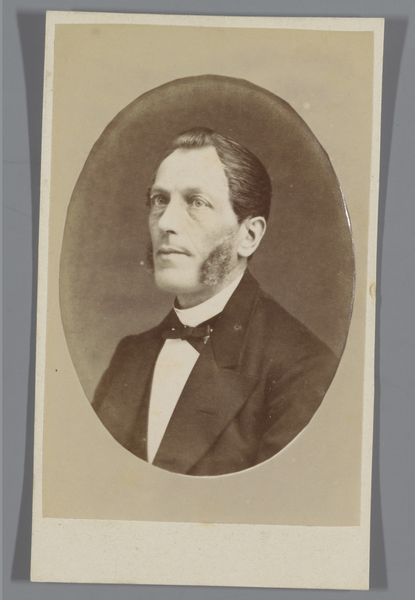

![Untitled [portrait of an unidentified man] by Jeremiah Gurney](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzZjZTFhYTVhLThjZjctNGYxYi1iYmIyLWQzNmZiNDE1MjAwNS82Y2UxYWE1YS04Y2Y3LTRmMWItYmJiMi1kMzZmYjQxNTIwMDVfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

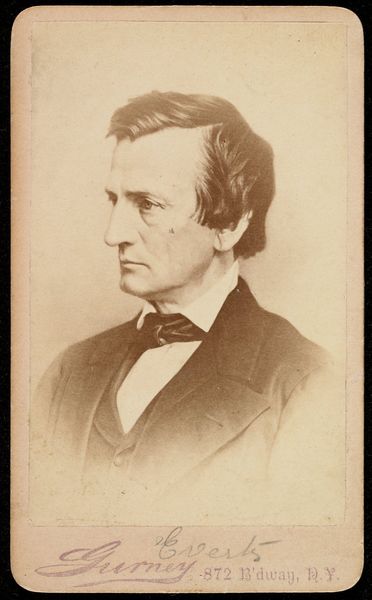

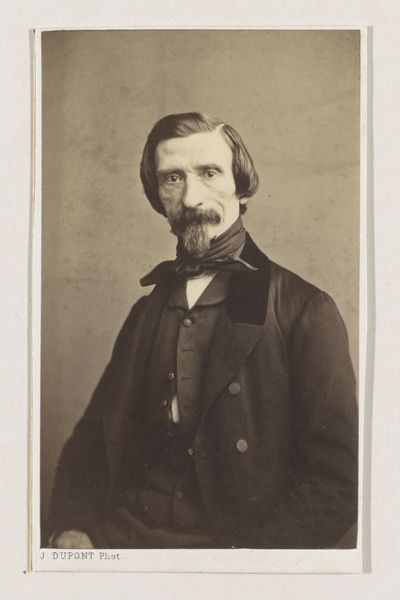

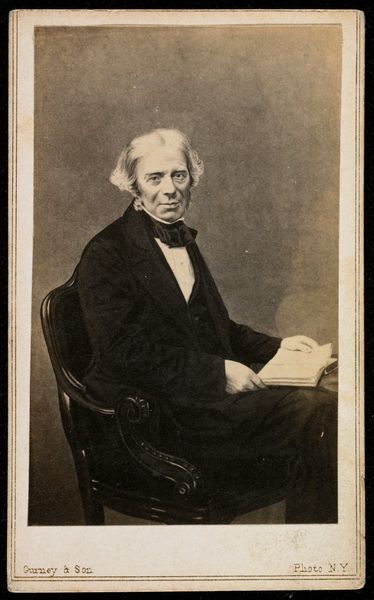

Untitled [portrait of an unidentified man] 1858 - 1869

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

academic-art

#

portrait art

Dimensions: 3 5/8 x 2 1/8 in. (9.21 x 5.4 cm) (image)4 x 2 7/16 in. (10.16 x 6.19 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This photograph, attributed to Jeremiah Gurney, presents us with an unnamed gentleman captured sometime between 1858 and 1869. Editor: There's such a piercing gaze; it hints at an untold story, a weariness perhaps, etched into his face. The subdued tonality really enhances that. Curator: Gurney operated a prominent studio in New York, catering to the elite. Portrait photography in that era offered a novel form of accessible visual representation, gradually democratizing portraiture previously exclusive to the wealthy. Editor: It's interesting that you say "democratizing portraiture," because while technically more accessible, this man embodies a very particular kind of mid-19th-century respectability, doesn't he? His high collar, the carefully tied scarf… they signal status. I almost see echoes of earlier Romantic poets, with that long hair and melancholy air. Curator: Exactly. The visual language being codified around this new medium had to grapple with existing social norms and aesthetic expectations. Consider how painted portraiture set precedents regarding posture, attire, and idealized representations of status that informed photographic portraits. It's not just about accurate representation; it's a social performance recorded by the camera. Editor: I notice also how direct his stare is. It feels so different from painted portraits of the time. Curator: Photography’s perceived indexicality — that direct link to reality — allowed for a new kind of engagement between the sitter and the viewer, and it influenced painting styles going forward, especially with the Impressionists. The development and use of gelatin-silver printing processes also led to greater clarity. Editor: I am struck, finally, by the lack of narrative context, given all the signals of personal history present. We can’t know his actual role in the era. That unknown almost becomes a potent symbol in itself. Curator: Precisely, that tension between presence and anonymity reveals much about photographic portraits in that period, I agree. Editor: He has made me see a new way of thinking of photographic subjects. Curator: I think he makes you think of everyone!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.