etching, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 171 mm, width 231 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

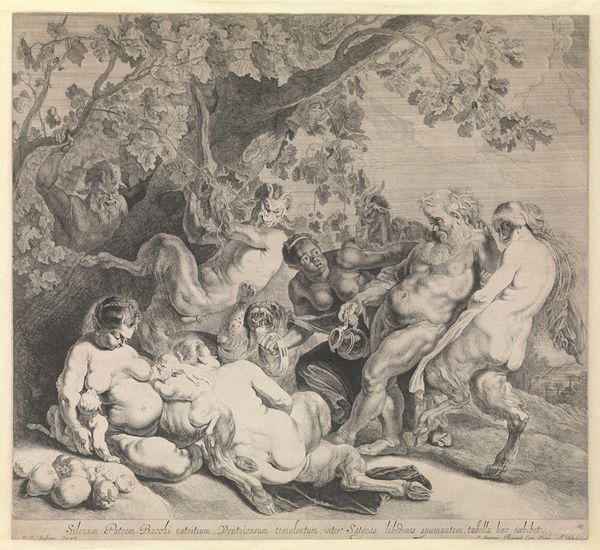

Curator: This is "Jupiter en Callisto," an etching and engraving made by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger, dating from somewhere between 1636 and 1670. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is just how much labor must have gone into creating all of this texture! The hatching and cross-hatching in this landscape are incredibly dense, almost textile-like in its intricacy. Curator: Absolutely, and that speaks to the artistic and socio-economic context of printmaking at that time. These prints were essentially multiples, a form of visual currency, widely circulated and consumed. Van de Passe was part of a family workshop, producing imagery for a broad audience. The cost was in the production. Editor: Tell me more about that cost. It looks like etching, in terms of how it's made. It wasn't just a singular etching? Curator: It looks like it's an etching reinforced by engraving. First etching provides a framework for the scene and then the finer detail is done by hand through the engraving tools. You've got the various tools needed; copper plates, acids, engraving burins - all of that went into the multiple works made from it. Editor: And we see the mythological narrative front and center, playing a critical role in shaping the viewing experience and overall understanding. It highlights the role of these mythological narratives within Baroque culture itself and in power dynamics between classes. Curator: The scene depicts Jupiter's deception of Callisto, a nymph of Diana, doesn't it? Look how vulnerable she is as Jupiter, disguised as Diana, approaches. The backdrop hints at that violence, despite the overt classical themes, of course. It reflects, I think, a broader fascination with Ovid's "Metamorphoses," but one tinged with contemporary social and political anxieties about female sexuality. Editor: I am still struck by the duality in this image and that complexity adds an enduring power, despite it merely being, at its root, something designed to mass produce visual data for an audience. Curator: It’s a testament to the artistic skill involved and really challenges our notions of what constitutes "high art" versus something merely "decorative." Editor: For me, the piece becomes a vehicle to reflect on social values in artmaking within early modern Europe. It also raises questions about how mythology can obscure power dynamics and the impact of cultural imagery. Curator: And for me, considering this in its original function provides us insight into workshop economies, and print’s function as not just art, but a commodity within burgeoning markets.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.