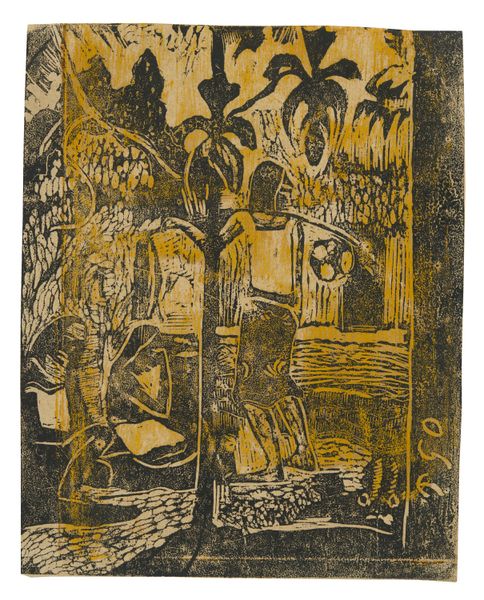

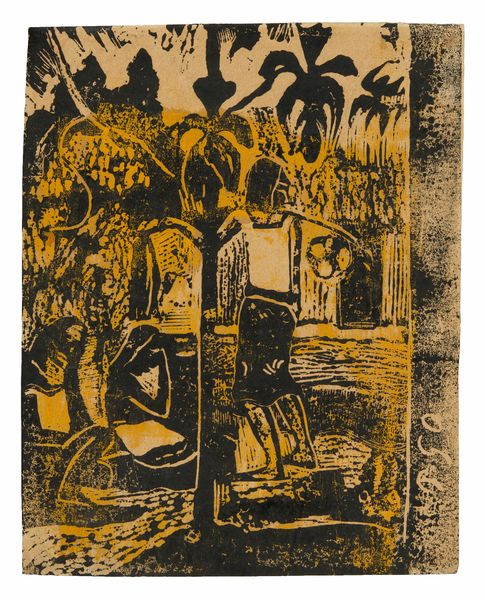

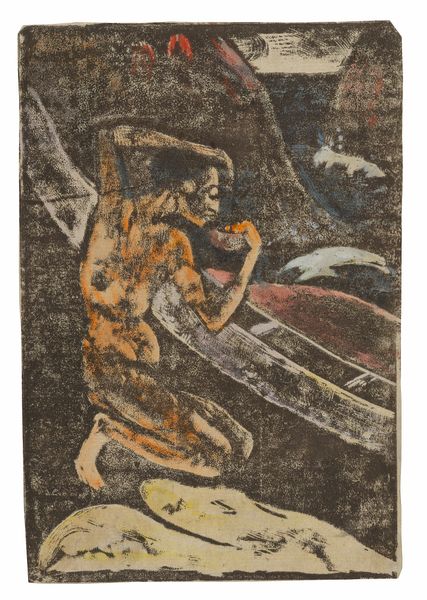

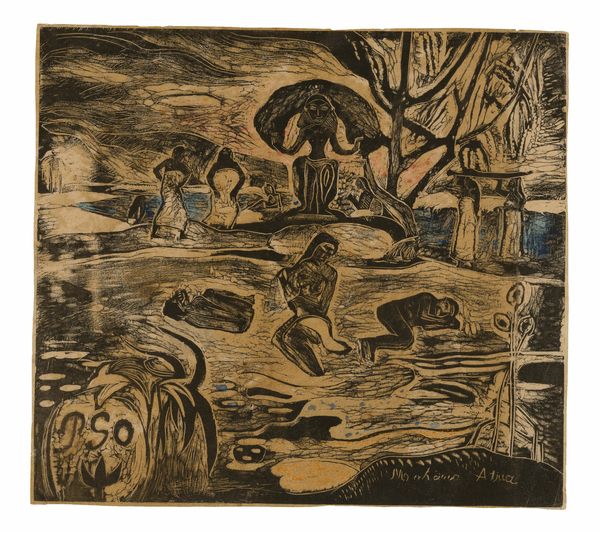

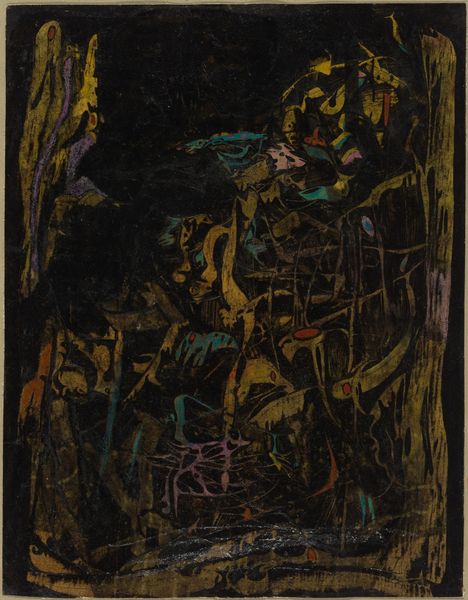

Dimensions: 145 × 118 mm (image); 147 × 120 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

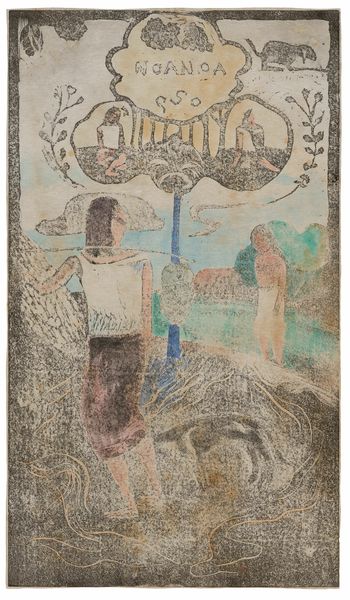

Curator: Paul Gauguin's woodcut "Noa Noa (Fragrant)," created between 1894 and 1895, whispers secrets of Tahiti from right here at the Art Institute of Chicago. What do you feel when you look at it? Editor: Immediately, a sense of tension. There’s a figure—likely a Tahitian woman given Gauguin's biography—caught between a dense, almost oppressive darkness on the left and a lighter, somewhat constructed-looking space on the right. It's intriguing. Curator: Constructed is a good word. Gauguin's Tahiti was, in many ways, a romantic fantasy, a refuge from the stifling conventions of Europe. This print is less about objective reality and more about subjective experience. Look at how he layers the woodcut with watercolor and colored pencil! Editor: Exactly, that layering speaks volumes. The woodcut, with its history as a medium for mass reproduction and accessibility, combined with watercolor, which lends itself to vibrant and highly expressive colors. The print becomes a statement of Gauguin's unique "primitive" vision against what he deemed decadent European modernity. He yearned to be reborn and create a new form of painting, as he put it. Curator: I hear you, but don't you think there’s something touchingly naive about it, too? He fled to an island paradise only to recreate it in his own image. He’s not showing us Tahiti so much as showing us Gauguin in Tahiti, searching to distill this authentic experience. Editor: Naive perhaps, but also deeply problematic. Gauguin’s vision romanticized and sexualized Polynesian women while profiting from a colonial system that dispossessed them. We have to recognize that while Gauguin pursued individual expression and the rejection of Western culture, he ended up exploiting a real culture. The history casts a shadow on the visual pleasures the print offers. Curator: I wrestle with that tension often with his work – its undeniably visual allure grappling with its thorny ethical implications. In that way, art reflects the flawed humans who create it, doesn't it? I'm reminded that nothing exists in a vacuum, no matter how "fragrant" it seems. Editor: Precisely. And by confronting that complexity, the richer, deeper meanings surface in works of art, however conflicting they may be.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.