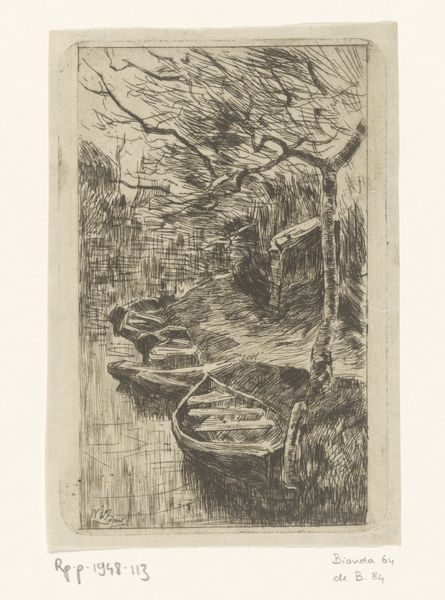

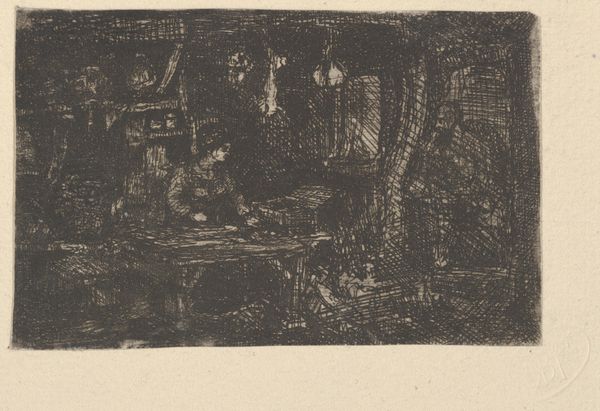

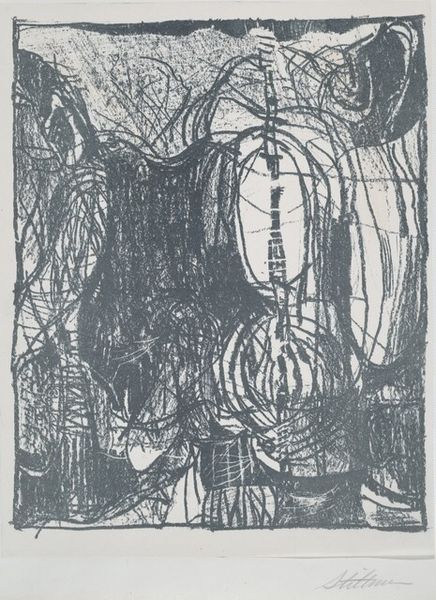

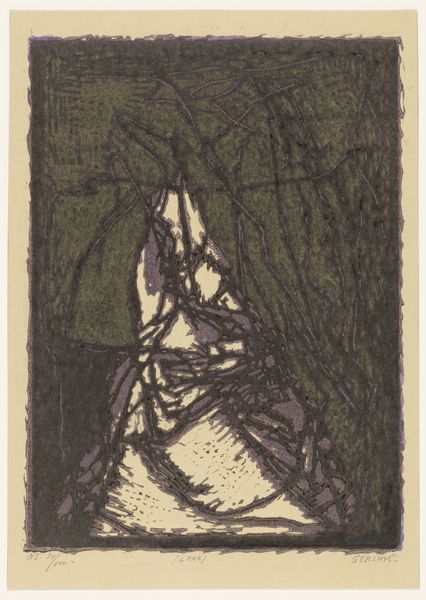

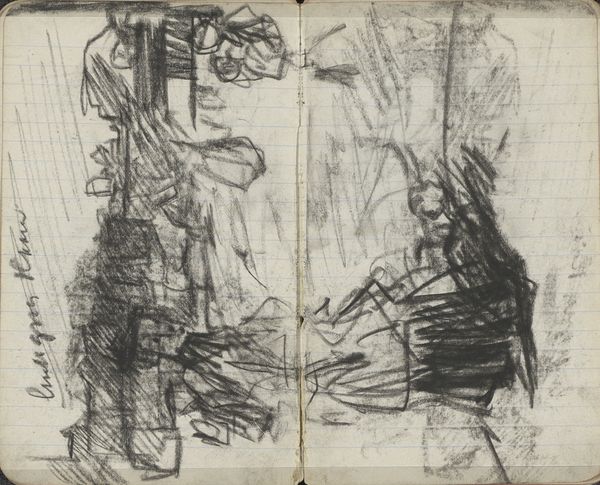

Intérieur d'un Malade (Interior of a Sick Person) 1839 - 1885

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

figuration

#

ink

Dimensions: Mount: 14 13/16 × 10 5/8 in. (37.6 × 27 cm) Plate: 3 7/8 × 2 15/16 in. (9.8 × 7.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Rodolphe Bresdin's "Intérieur d'un Malade," or "Interior of a Sick Person," a compelling etching in ink from sometime between 1839 and 1885. Editor: What strikes me immediately is the claustrophobia – the density of lines and shapes creates a feeling of being closed in, mirroring, perhaps, the sick person's confinement. It's dark, heavy. Curator: Indeed, Bresdin's masterful control of the etching process allows him to build up such textures. Look at how he manipulates the density of the ink to create tonal variations. His labour is visible, even palpable here. Editor: And that labour certainly underscores the image’s political weight. Who are the sick? What societal conditions produce illness and suffering? It makes me consider broader issues of access to healthcare, class disparities, and societal neglect. Curator: Consider also the technical skill and resourcefulness demanded of printmaking at the time. Etchings like these were more easily disseminated than original drawings, allowing for a wider distribution of his vision. The role of printed matter and its material consumption should not be underestimated. Editor: Absolutely. And within that distribution, Bresdin might have wanted his audience to consider that a space of sickness isn't a vacuum. Social conditions shape the interior life; identity and personhood is challenged through the circumstance of being ill and the way it’s observed, like a spectacle, or concealed within the room. Curator: Do you see Bresdin's perspective here as exploitative? Considering that this work comes from an artist who lived a difficult life himself, always bordering poverty. The conditions of labor impact perception. Editor: Exploitative might be too strong. But there's a tension, isn’t there? Perhaps a self-identification, as well as the recognition of broader precarity—his and others'—at play. The social context demands we look critically at not just who is depicted, but *how*. Curator: The how is always connected to what and why...I’m fascinated by the level of intricacy Bresdin achieves. Etching demands painstaking preparation of the plate and careful application of the acid resist. One tiny error can ruin hours of work. Editor: And yet that imperfect, handmade quality conveys its own truths—narrating a reality far more nuanced than a slicker rendering ever could. Curator: The way materials can convey so many dimensions still leaves me in awe. Editor: Exactly, these layered observations help to untangle assumptions and offer a more profound awareness about humanity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.