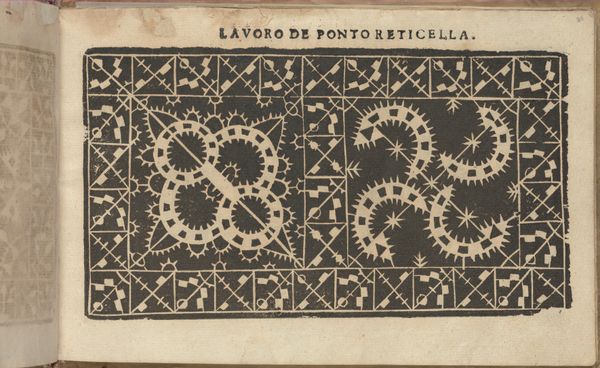

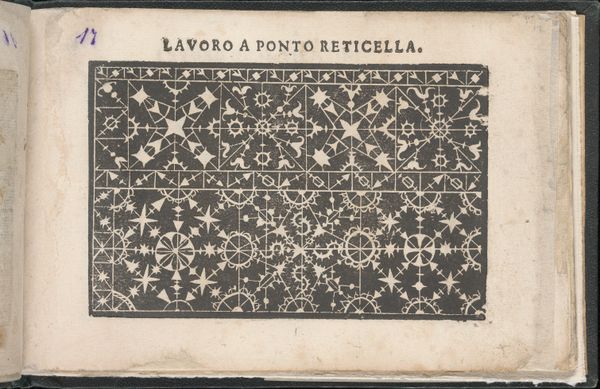

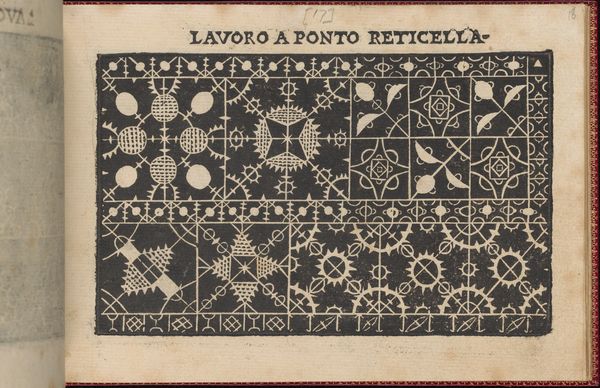

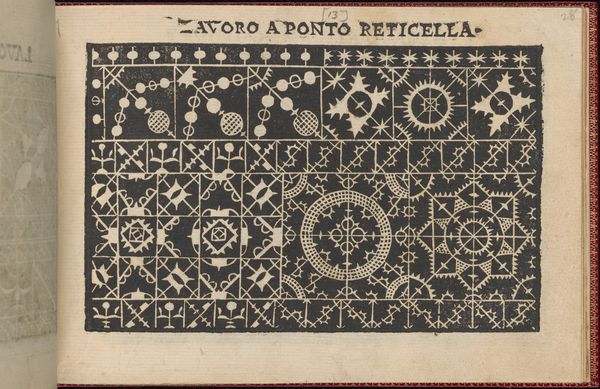

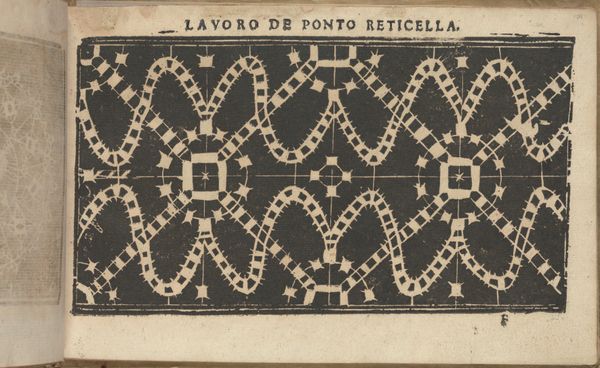

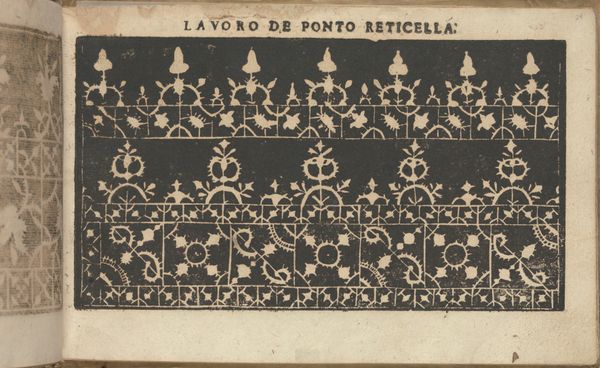

Studio delle virtuose Dame, page 29 (recto) 1597

0:00

0:00

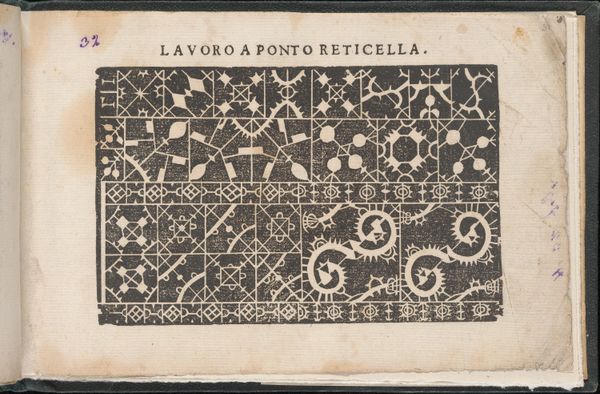

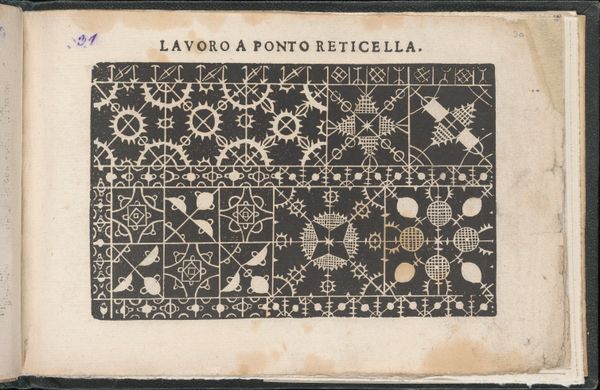

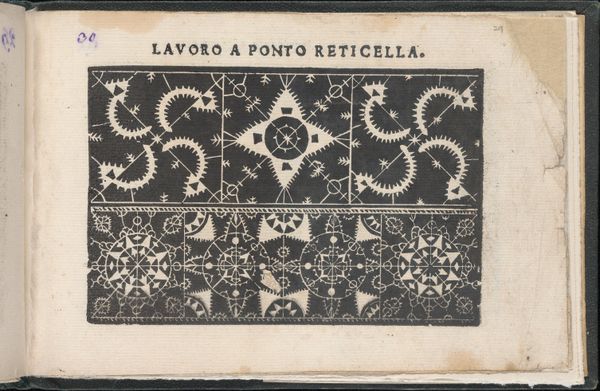

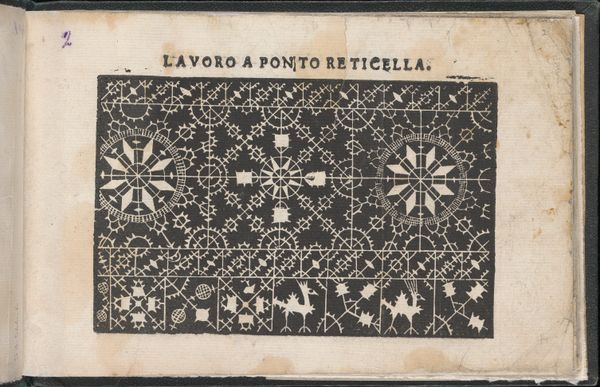

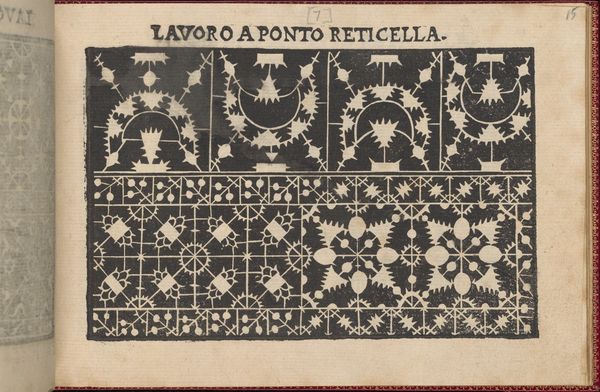

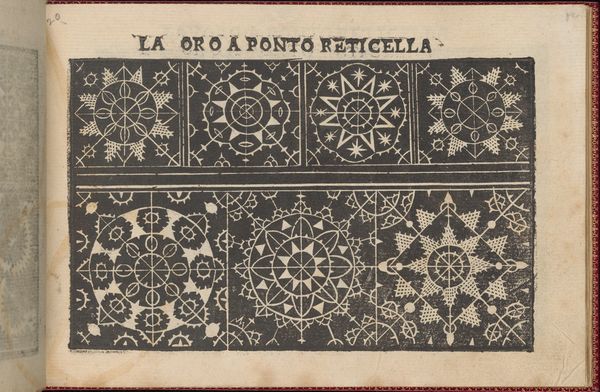

drawing, ornament, print, textile

#

drawing

#

ornament

# print

#

book

#

textile

#

geometric

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: Overall: 5 1/2 x 8 1/16 in. (14 x 20.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately, I see a kind of ordered chaos, like a complex engine disassembled and laid flat. The contrasting black ink on the ivory page lends a stark, diagrammatic quality. Editor: That's a great observation. What we're viewing here is "Studio delle virtuose Dame, page 29 (recto)" created by Isabella Catanea Parasole in 1597. This piece is a print from a book, meant to serve as patterns for reticella lacework. Curator: Reticella, meaning "little net," was incredibly fashionable at the time, used to adorn everything from collars to cuffs. Seeing this, I can’t help but think about the materiality of the textile it intended to create—the very labor-intensive, meticulous nature of lacemaking. Editor: Exactly. Consider the societal implications of these designs—meant specifically for "virtuous ladies" as the title suggests. Parasole’s designs offered a sanctioned creative outlet but were still within the confines of expected gender roles of the time. How were these patterns policed in terms of who had access to them or could afford the necessary tools and labor to realize them? Curator: I see the political statement, absolutely. This book became both empowering and restrictive, which leads to the tension felt as an art object. The grid within which those stars, leaves and geometrical components are built becomes apparent, so that what appears ornamental and frivolous is structured on an ironclad system of organization. What do you think about this black and white medium? Editor: The monochrome enforces the geometric grid, almost a proto-digital aesthetic—binary code of the needlepoint world. You begin to reflect on who these books were really designed to serve – often wealthy patrons or aspiring ladies of the court seeking social mobility via displaying taste. Curator: Absolutely. As viewers, it reminds us to question the accessibility of luxury and how prescribed female skill sets were interwoven within Renaissance Italian socio-economic structure. Editor: Yes, the materiality of luxury items then—the labor that underpinned them and the social strata that they reinforced—is essential. The repetitive motion needed is akin to factory working as labor became further divided within communities of craftswomen and noble families alike. Curator: I’m leaving here more aware of how patterns in history often cloak structures of power, quite literally stitched into the fabric of our society. Editor: And for me, considering Parasole's original book as a means to understand artistic process and how methods of material making influenced women's rights back in the Italian Reinassance has shifted my viewpoint on how value gets attributed to objects of all kinds.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.