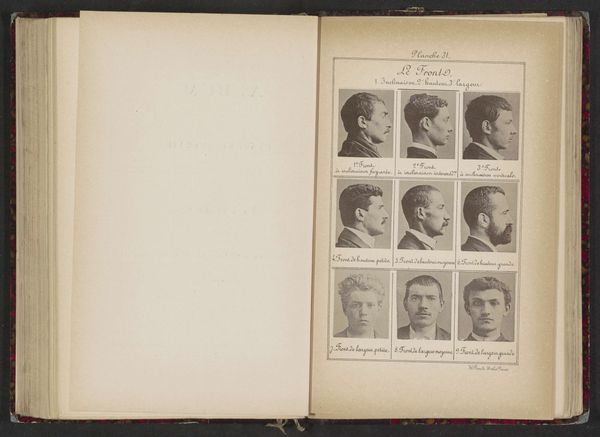

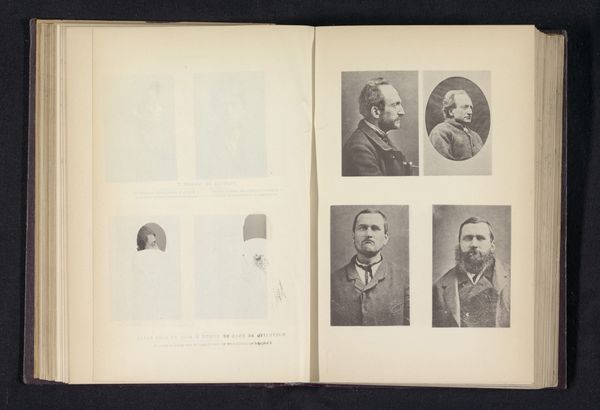

Portretten van een jeugdige crimineel, gemaakt na zijn eerste en na zijn tweede arrestatie before 1891

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

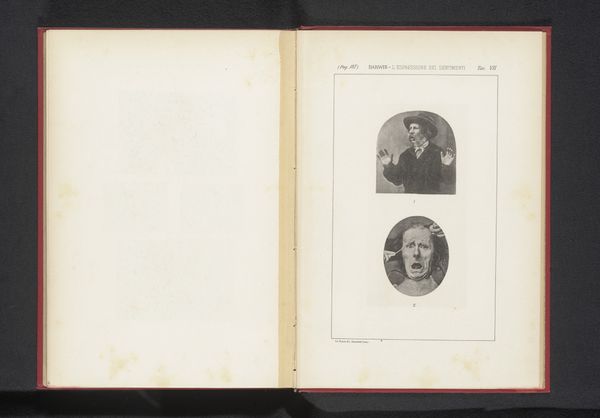

Curator: So here we have a rather fascinating, and frankly, unsettling series of gelatin-silver prints, dated before 1891. They're titled, "Portretten van een jeugdige crimineel, gemaakt na zijn eerste en na zijn tweede arrestatie" – portraits of a young criminal, taken after his first and second arrests. Look at that contrast between the top and bottom images, as if we're watching a fragile seedling trying to break through concrete, but… it’s still concrete. Editor: They’re bleak, aren’t they? The top set almost exudes a feral defiance, and then beneath, that posture just collapses. The images feel incredibly dehumanizing – reducing him to just mug shots. What strikes me is how the photographs are arranged in the book layout. It frames not art, but a system. Curator: Exactly! And you notice the almost scientific gaze. There's this prevailing idea back then to classify and understand criminality through physiognomy—linking facial features to character, as if crime was etched onto his very face by forces immutable! That format is chilling. Did these images help build or solidify an idea of a "criminal type" at the time? Editor: It absolutely reinforces existing biases. You see how easily “science” became a tool of control. Gelatin-silver prints, by their very nature as a reproducible medium, could rapidly disseminate these biased ideas, normalizing them. Think of how such portraits might have circulated in police training, shaping perceptions and thus outcomes, reinforcing power dynamics. Curator: It’s troubling to consider the production behind them, this constant flow from bodies to police files. Each arrest like a new run off the printing press. What does repeated photography do to our subject—the person repeatedly photographed? Can we think of these prints as yet another way of processing the criminal subject into… an object? A ghost, perhaps? Editor: A specter certainly… a constant, ghostly, visual reminder, re-presented in varying degrees of “realism,” so we can remember to stay wary. Even today, look at the visual language used in “true crime” documentaries and media. It carries a lot of that baggage and has real effects. Curator: To stare back now across time. How complicit we may all be in structures unseen. And… even with that knowledge, still needing to look to try and learn what he couldn't tell us. Editor: It really exposes the weight that materials – here the very reproducible image itself – can bear, perpetuating narratives far beyond the subject's own life, even altering or erasing the conditions in which that life unfolds. Powerful stuff.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.