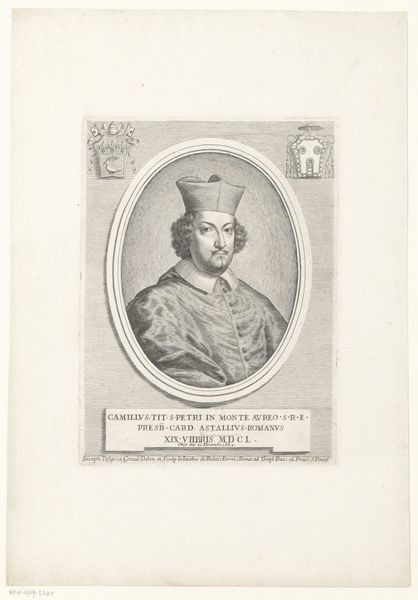

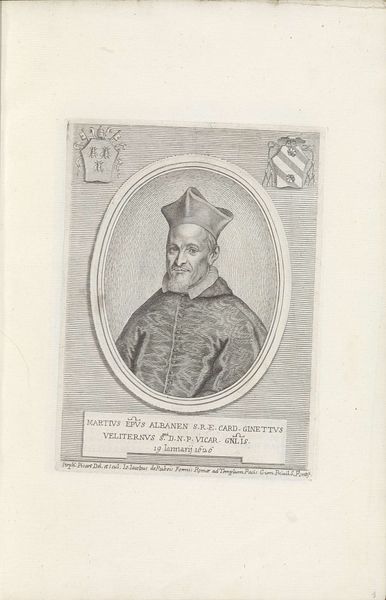

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is a print, an engraving to be precise, of Cardinal Francesco Maria Brancaccio, made in 1658 by Giuseppe Maria Testana. It feels very formal, but the textures achieved through the engraving are pretty impressive. What can you tell me about this from your perspective? Curator: I see an intentional engagement with material processes reflecting socio-economic realities. Engraving, as a reproductive medium, served a vital role in disseminating images of power and influence. Think of the labour involved in creating this matrix. Each line painstakingly etched, translating social standing into a tangible commodity. Editor: So, you're saying the act of creating multiple copies, the labour and materials used, are as important as the subject portrayed? Curator: Precisely! Consider the networks involved: the artist, the patron commissioning the work, and the consumers who purchased these prints. These portraits were, in essence, commodities, traded and consumed within a specific social context to propagate power, both religiously and politically. This wasn't just about art, but also about how art functions within broader systems of exchange. What would owning something like this have meant back then, or even now? Editor: I never thought about prints being traded like commodities, or how the artist's labour contributed to the Cardinal's public image. I guess it challenges this high/low art distinction. Curator: Exactly. This piece is an entry point to questioning those boundaries. We move past solely focusing on the artistic genius and contemplate the systems that enabled its production and reception. Editor: It changes how I see the purpose of portraits back then and even now, that's for sure. Thanks! Curator: Absolutely. It is imperative to acknowledge the artist’s method to comprehend art in all of its social and historical intricacies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.