print, ink, woodblock-print, pencil

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

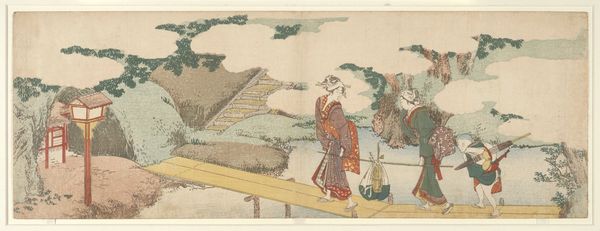

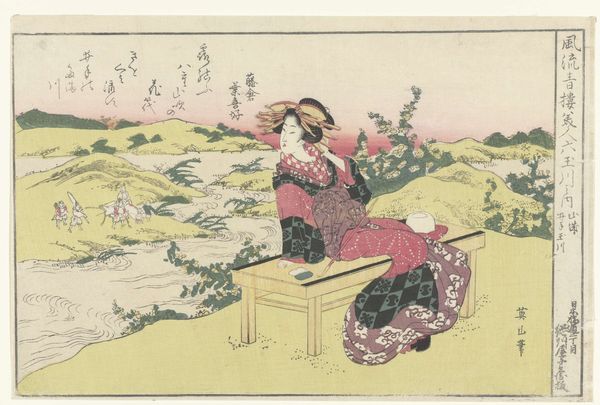

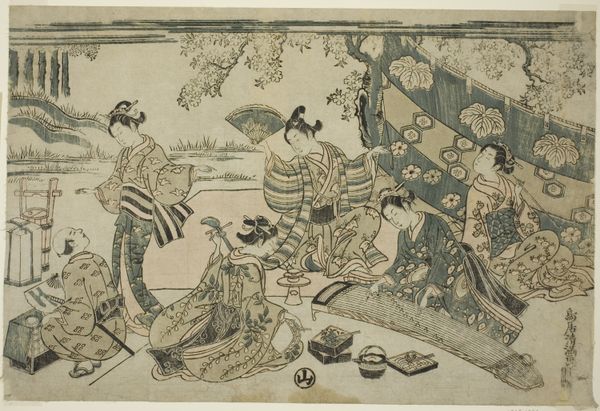

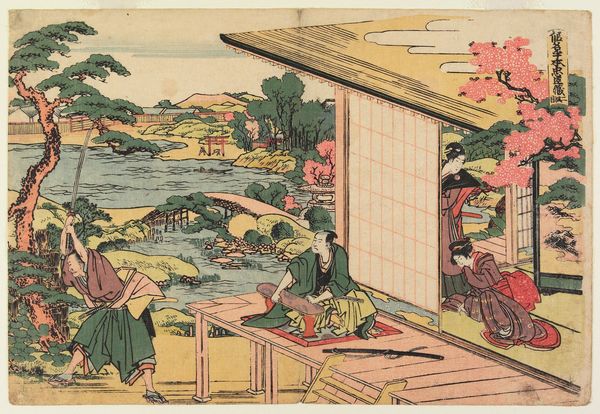

Dimensions: 7 5/16 × 20 1/16 in. (18.5 × 51 cm) (image, sheet, ebangire)

Copyright: Public Domain

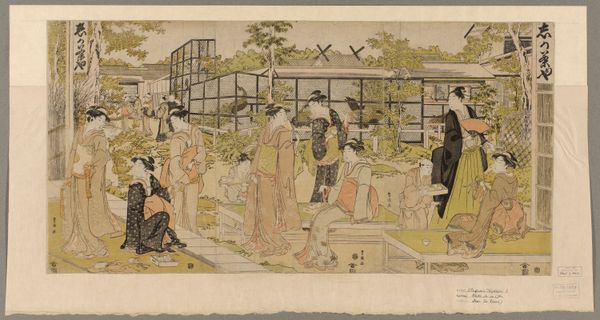

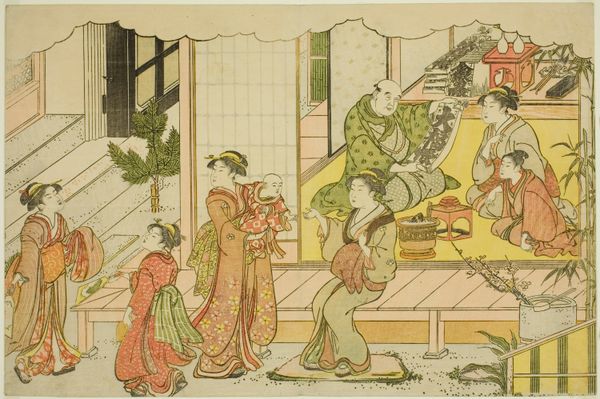

Curator: The work we are looking at is a print titled "Goldfish Vendor," made circa the 19th century by Katsushika Hokusai. Editor: The print feels simultaneously dynamic and calm; there’s a sense of everyday life elevated by a delicate treatment of line and color. The light palette gives it a dreamy feeling. Curator: Hokusai’s pieces like this one give a glimpse into Edo-period Japan, showing the social and cultural rituals of the time, particularly concerning commerce. Note the leisurely pace and the subtle interactions between vendor and client. These scenes gained popularity during this time due to a burgeoning merchant class and increased urbanization. Editor: I am also thinking about the role gender plays here. Look at the three figures. On the right, you have the seated figure wearing several layers, and in the middle you see another woman also lavishly clothed, as opposed to the boy who is not only reaching out in a gesture, but also in less clothing than the other figures. It raises questions about the relationship between class, gender, labor and art. Curator: Exactly. The very materiality of ukiyo-e prints meant they could circulate widely and become integral to consumer culture, solidifying certain gendered and social roles through repeated images. You're seeing it depicted here. And this helped shape Japanese self-perception as well as Western ideas of Japan. Editor: Yes, the reception and the construction of the gaze. Who is invited into this moment, who gets a right to consume the image, and on whose terms? But if we view it as a window into a specific time and space, does that freeze or limit our analysis? The vendor remains timeless while specific to his role within Edo society. Curator: That tension, between the specific and the timeless, is always there when dealing with art of the past. How it reflects the power structures of its day is one thing, but then there's the ongoing way these works function to negotiate identity and meaning now. This piece prompts questions around those issues, don’t you think? Editor: Definitely. It offers us not just a historical artifact, but also a complex text about society, labor, and gender. The way Hokusai captured it allows these dialogues across centuries.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

In addition to his commercial woodblock designs for mass consumption, Hokusai made a large number of surimono, or deluxe prints for private clients. This print was once part of an announcement, program, or poetry compilation, but the accompanying information that might have identified the purpose has been trimmed away. The scene shows a goldfish vendor by her tank under the trees. The Japanese first imported goldfish from China in the 16th century, fascinated by their novelty and shimmering colors. By the early 19th century, goldfish had become affordable pets for ordinary citizens. Every summer, they were a popular commodity because, psychologically at least, viewing fish swimming in delicate glass bowls tempered the heat. In this print, a little boy excitedly holds up a glass container, perhaps pleading with his mother to buy a goldfish.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.