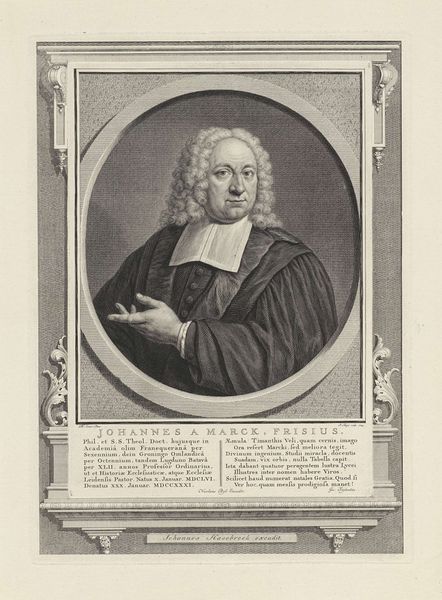

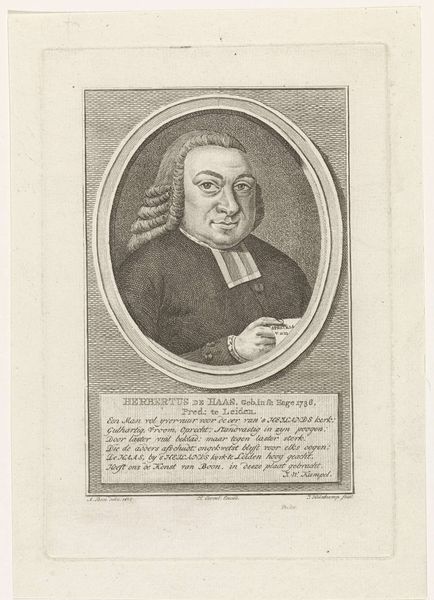

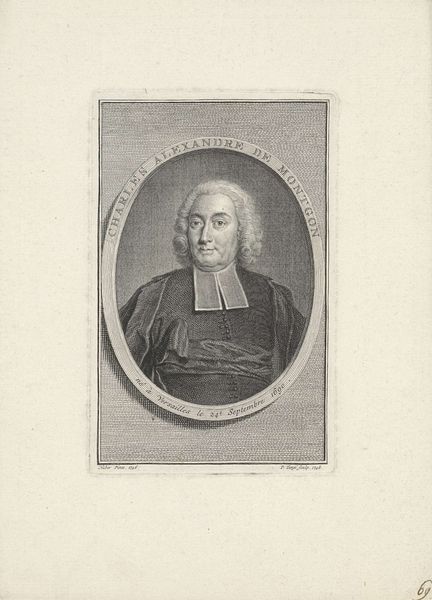

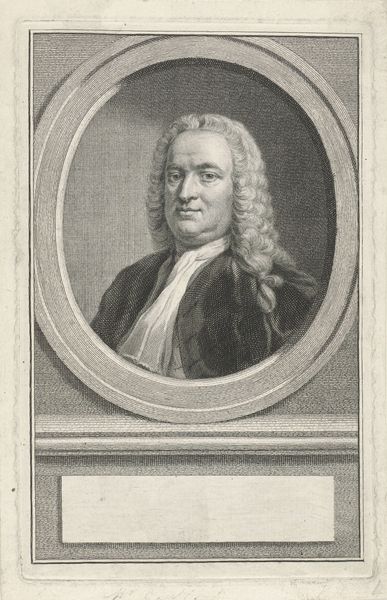

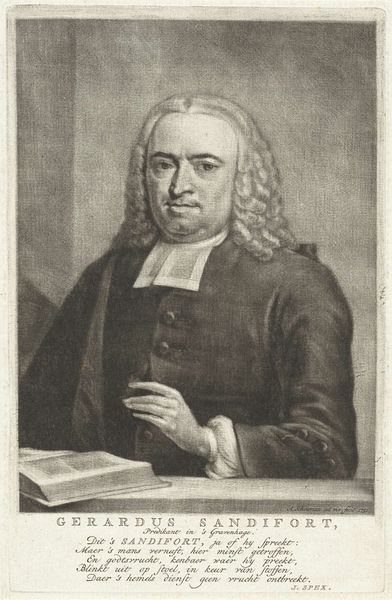

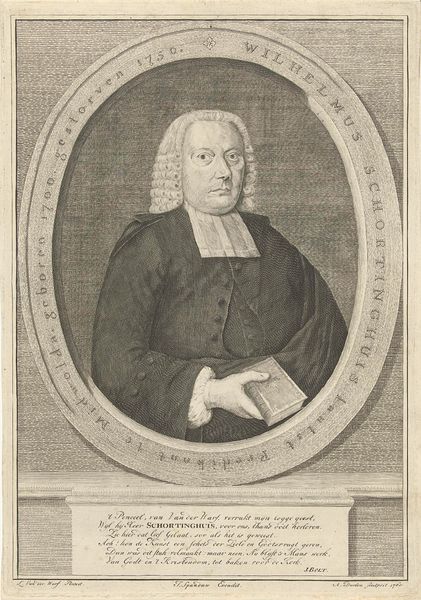

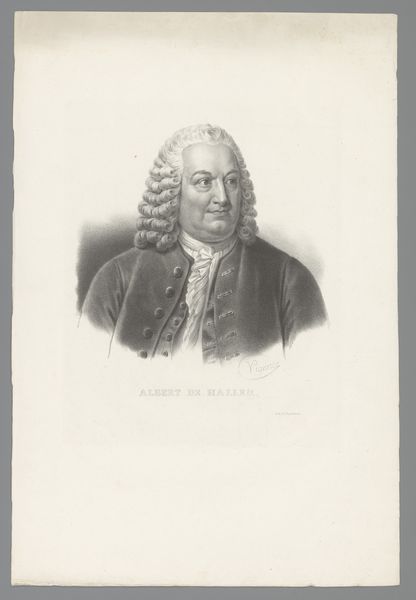

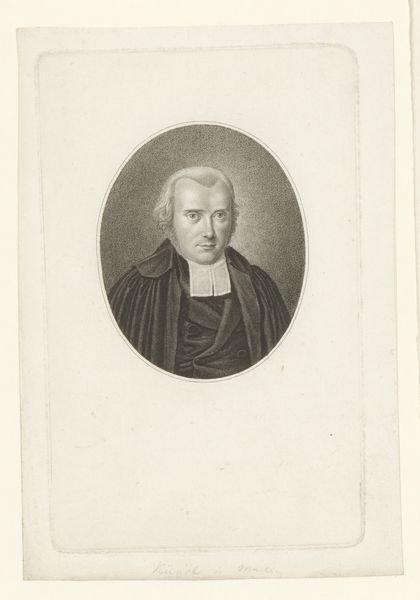

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 189 mm, width 129 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Pieter de Mare’s "Portret van Didericus van der Kemp", made sometime between 1781 and 1783. It's an engraving, and I’m struck by the sheer precision of the lines. What stands out to you about the material process here? Curator: For me, the engraving medium itself speaks volumes. Think about the labour involved. Each tiny line is deliberately etched into the plate, then inked and pressed onto the paper. This wasn't a quick sketch; it was a calculated act of reproduction, designed for dissemination. We need to ask, why engraving, and what implications did that hold for the art market? Editor: So, you're saying the choice of engraving implies something about how it was meant to be circulated? Curator: Exactly. Consider the context. This is Neoclassicism, a period obsessed with reason and order. The precise lines of the engraving, the easily reproducible image, speaks to this desire to make knowledge accessible, to spread ideas efficiently. The labour-intensive process paradoxically serves to democratize the image, or at least to control its reproduction for specific social purposes. Do you see the contrast there? Editor: Yes, it is quite interesting to think that all those small incisions result in potentially widespread image dissemination. Was this typical? Curator: For portraits, especially of prominent figures, it was a common way to circulate their image. This connects directly to issues of power, influence, and even celebrity of the day. Think about the social status someone like Didericus van der Kemp held, and the statement made through reproducing his image using such a readily accessible, yet carefully controlled method. What does it tell you about the engraver's role as artisan versus artist, in this context? Editor: I hadn't considered that aspect of labor and material dissemination before, I will certainly be keeping an eye out from now on! Curator: Indeed. Looking closer can unearth new facets even in pieces we may assume we know.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.