engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 276 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

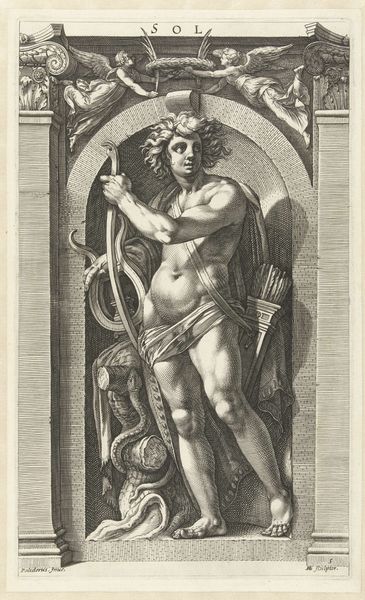

Curator: Let's discuss "Allegory of Honor" by Pieter van den Berge, created sometime between 1686 and 1737. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you about it initially? Editor: Well, the first thing I notice is the starkness of the engraving medium. The monochrome palette heightens the almost severe classicism of the scene, dominated by this cherubic figure floating amidst symbols. The sharp contrast emphasizes the idealized form and textures of the objects surrounding him. Curator: Indeed. The allegory functions within a specific socio-political framework. Honor in this context wouldn’t be simply personal integrity; it refers to public service, aristocratic virtue, and fulfilling one's duty to the state and to God. Note the arrangement of objects suggesting earthly and heavenly achievements. Editor: Semiotically speaking, those objects are potent. The hourglass, partially obscured, represents mortality and the fleeting nature of earthly achievements, while the laurel wreath, held aloft by the winged cherub, represents triumph and enduring fame. The ribbons linking them introduce a graceful linearity that mitigates the engraving’s rigidity. Curator: And look at the text at the bottom. In Dutch and French, it elucidates the image by celebrating "virtue" and the pursuit of worthy service. Engravings like these were often commissioned as propaganda, circulating specific ideas about the ruling class. They shaped public perception. Editor: The way the artist uses line to build form is quite sophisticated. Notice the density of lines to convey shadow and volume, particularly in the drapery behind the cherub, creating a complex interplay of light and dark. The texture becomes almost palpable despite the print's inherent flatness. Curator: Right. But those artistic decisions also helped communicate clearly in a medium intended for broad dissemination. Van den Berge and others were crafting very pointed statements, shaping and reinforcing existing hierarchies and moral codes within 17th and 18th-century Dutch society. It shows that even simple engravings like these reflect complicated social structures. Editor: Examining the balance of composition, use of symbolism and understanding it was indeed propaganda really makes one realize there are layers of context even with works of art using what may seem to be rudimentary technqiues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.