print, etching

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

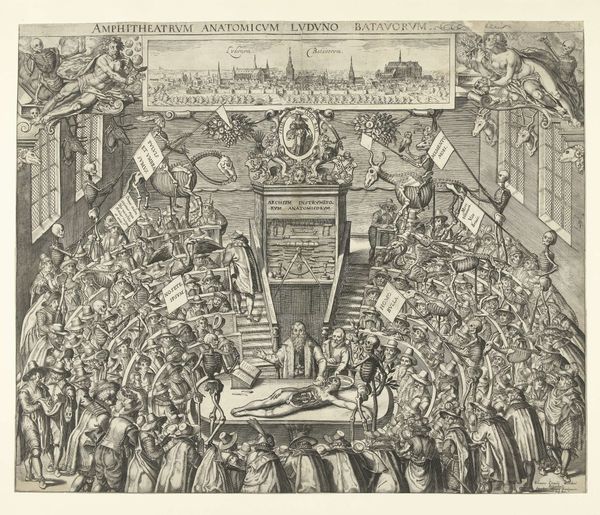

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 380 mm, width 489 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

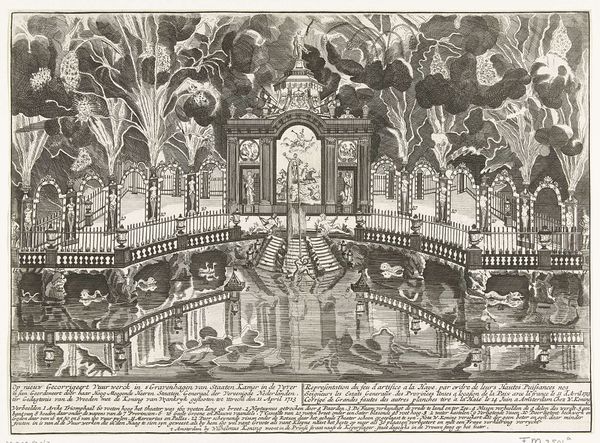

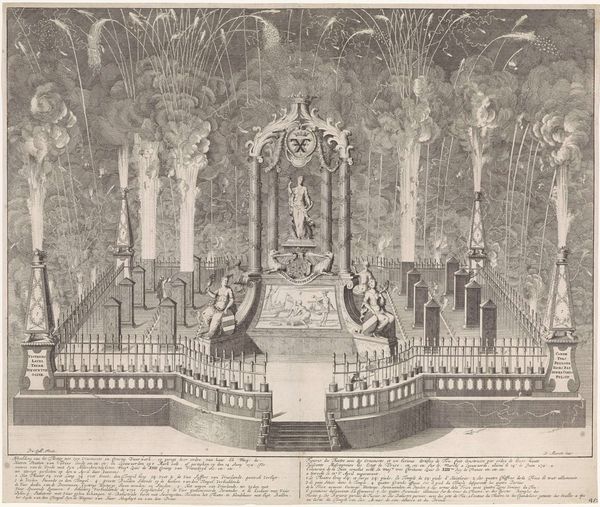

Curator: Daniel Marot’s etching, “Fireworks Celebrating the Victory at Vigo, 1702,” made between 1702 and 1704, depicts a meticulously designed spectacle. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your first impressions? Editor: Chaos. It's like trying to contain a tempest on paper. The fireworks are rendered as explosions of furious energy. I am instantly struck by the medium, by the etcher’s line as a form of labour – and it’s dizzying in its sheer density. Curator: It's a record of a public performance, an orchestration of gunpowder and light, yet etched for a more lasting, if smaller, public. Marot was deeply involved in the design of courtly spectacle; one can imagine the societal pressure on artists and printmakers to visually amplify moments like the Battle of Vigo Bay. Editor: The engraving process itself emphasizes labour and reproducibility – it makes you wonder about the cost of the materials – the metal, ink, and paper, as well as the value attributed to this act of immortalization by printmaking? The pomp is undercut slightly by this feeling; it's mass-produced propaganda on some level. Curator: Propaganda, celebration, commemoration… these were all entangled. Consider the central structure, adorned with allegorical figures. It anchors the ephemeral fireworks display to something more permanent—state power and military might. What looks chaotic at first glance is highly structured and calculated. Editor: I do wonder what that original ephemeral display was like, if it felt as claustrophobic as the etching suggests. Do you think it might have been a touch… overwhelming for the average spectator? And that monument at the centre is intriguing—almost an assertion of permanence amidst explosive ephemerality, an anchor for power. Curator: These celebratory artworks solidify and disseminate political narratives and historical occurrences to the population. What we see reflected is less the spontaneity of celebration and more the machinery of image-making for cultural indoctrination. Editor: Which makes you ponder what that original lived experience truly consisted of. As objects made from metal and paper, printed by hand, we can truly question not only the intent behind them but what this etching now, represents for the modern audience. A fragment, or just another artifact?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.