print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 144 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

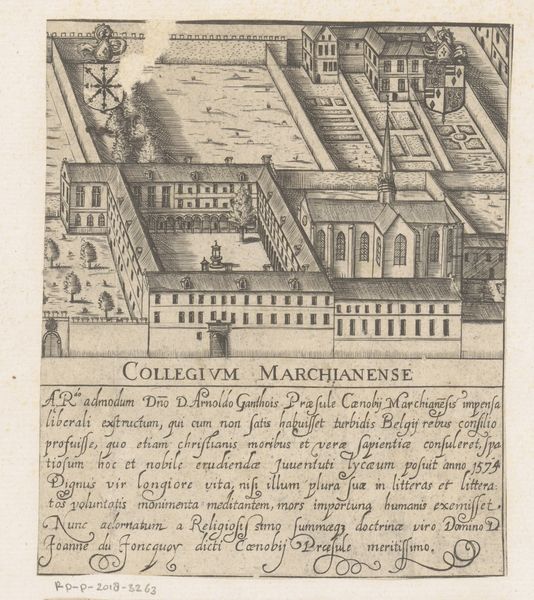

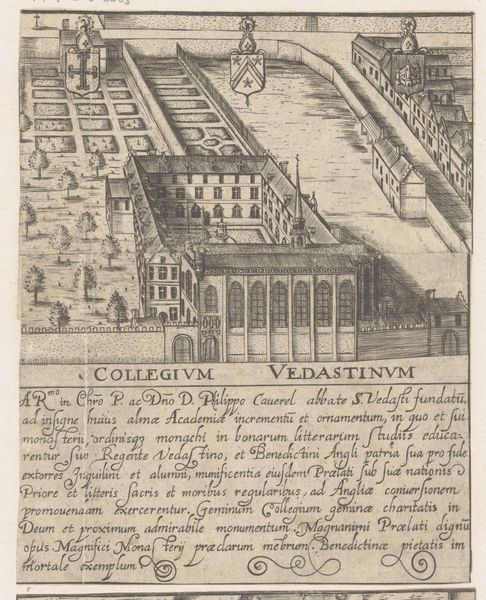

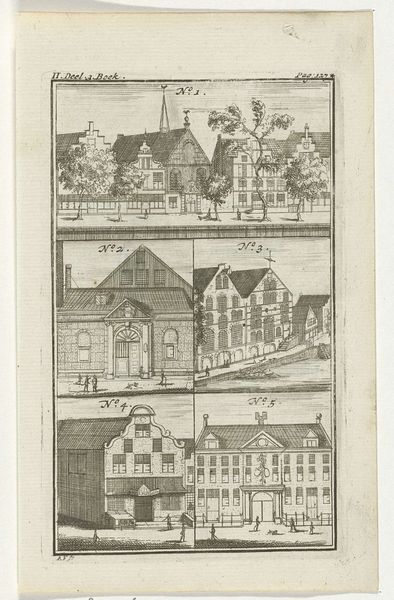

Curator: Looking at this engraving, titled "College van Mottanum," likely created between 1605 and 1680 by Filippo Ferrari, I’m struck by its focus on power structures manifested in architectural space. What is your initial reaction? Editor: Austerity. A sense of confinement. The building, dominating the small city beneath, projects an atmosphere of formal rigidity. All those repeating windows…like eyes scrutinizing something. What is the significance of the shield on top? Curator: Considering the era, that’s almost certainly a heraldic emblem denoting the family or institution associated with the college. Beyond representing family lineage and power, these visual cues underscore a clear hierarchy embedded within the building’s design itself. Think of how such signs reinforce status for students and administrators within. Editor: The iconography is strong. The rigid structure with its defensive walls could represent the knowledge or traditions the institution is sworn to protect. And there, within the courtyard, we find a modest fountain of knowledge and civic access, but note, it lies within heavily protected grounds. Is the light in this rendering accurate? The walls cast ominous shadows, no? Curator: That’s a very keen observation, especially within the socio-political lens. It’s true the high contrast exaggerates the darkness. The chiaroscuro emphasizes the restrictive environment the college symbolizes; perhaps the lack of light speaks to limitations imposed by religious doctrine. The college sits high on what looks to be a protected citadel and keeps a distance from all life beneath. The walls stand in stark contrast to any signs of street commerce below, suggesting limited connectivity between students and townsfolk. Editor: But the orderly construction is interesting when contextualized against the tumult and the chaos happening throughout Europe at the time of its original inscription, 1609. There are some virtues worth recognizing here, no? Civic responsibility through structured architectural principles. Curator: Indeed! It would be myopic not to see that some residents of this city likely valued its structural role in organizing their public life. However, by interrogating whose “civic life” gets promoted here, and whose doesn't, we begin to appreciate the full extent to which structures such as these were also apparatuses of social control. Editor: This discussion shifted my initial impression from purely negative to one that appreciates complex duality, both shadow and illumination. What began with personal perception evolves through scholarly interpretation into something both lasting and vital!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.