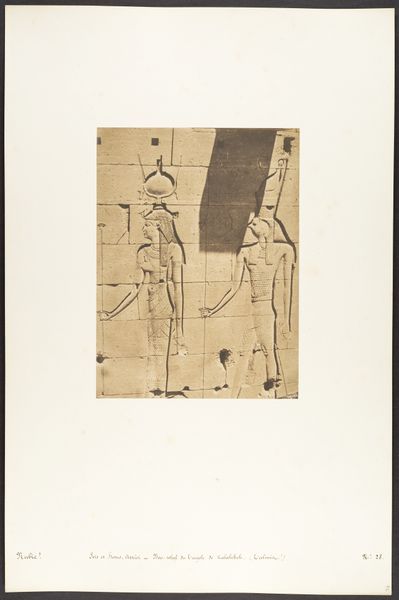

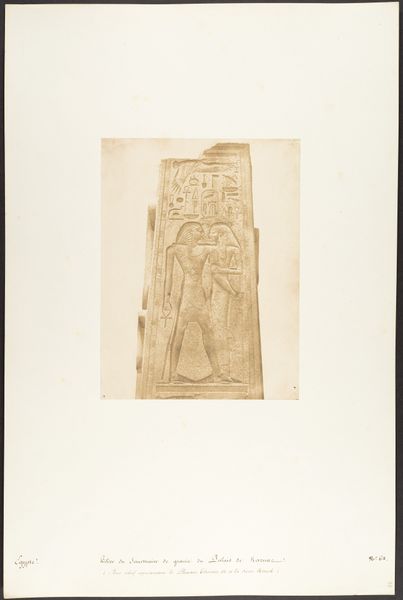

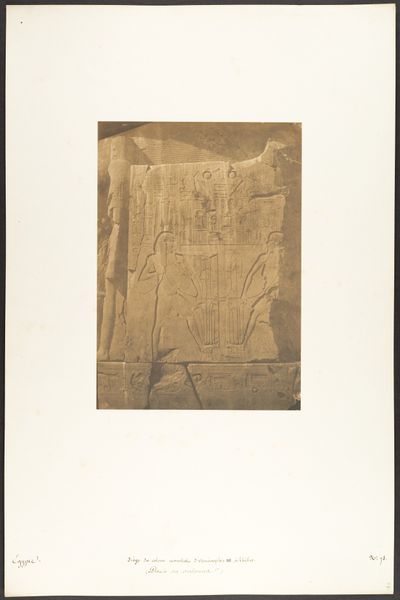

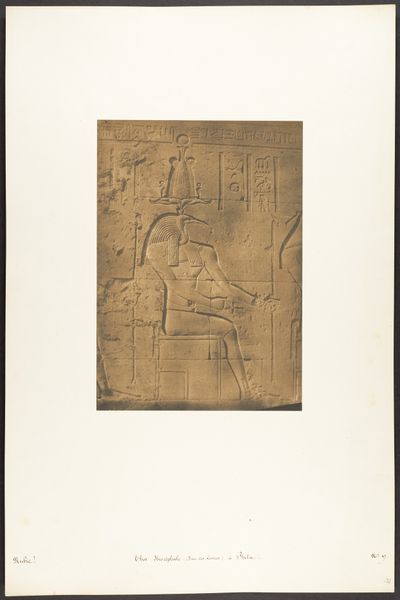

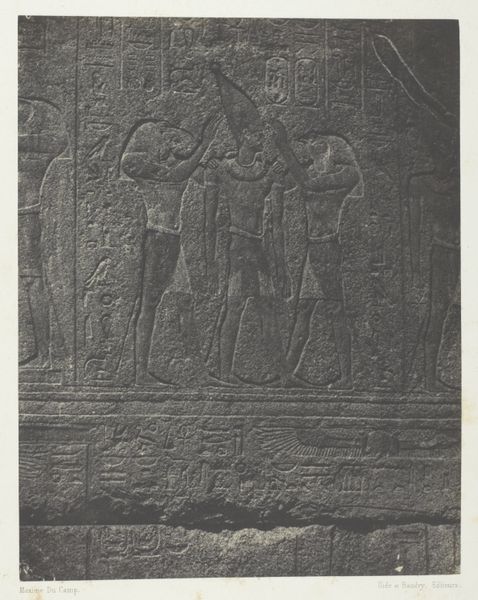

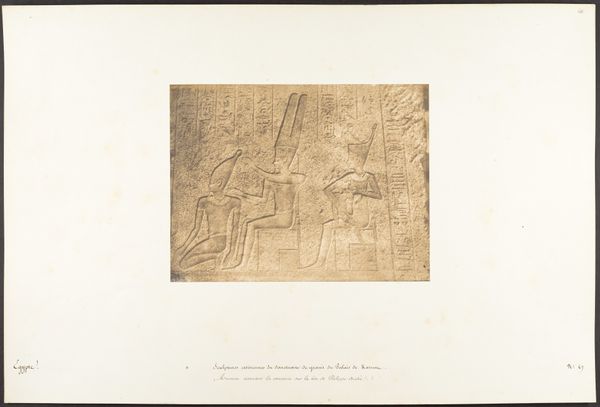

Sculptures extérieures du Santuaire de granit du palais de Karnac (Sacre de Philippe-Aridée par les Dieux Thot et Hor-hat) 1849 - 1850

0:00

0:00

relief, photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

relief

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 8 1/4 × 6 7/16 in. (21 × 16.3 cm) Mount: 18 11/16 × 12 5/16 in. (47.5 × 31.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, taken by Maxime Du Camp between 1849 and 1850, documents a relief from the exterior sculptures of the granite sanctuary at the Palace of Karnak. It depicts the sacre, or coronation, of Philippe-Arideus by the gods Thoth and Hor-hat. Editor: Immediately, the stoicism of the figures jumps out. It’s almost austere, but the intricate hieroglyphs and the weight of the stone hints at a more profound narrative of power and legitimacy being built. Curator: Power, indeed. The choice of depicting a coronation—a pivotal moment of kingship—points to the enduring symbolic weight these images held. Ritual, the sacred... it's all here. Thoth, with his ibis head, and Hor-hat, the falcon, are bestowing divine right. Editor: But isn’t there also a vulnerability present? Philippe-Arideus, a somewhat obscure figure, needed that validation. Highlighting this scene underscores not just authority, but the social structures needed to manufacture a ruler's authority. Who benefits from that validation? Curator: The gods themselves! Through images and belief, the legitimacy of the divinely sanctioned order is maintained. Think about how symbols operate, though—the regalia, the animal heads—these weren’t arbitrary choices. They resonated with centuries of tradition, evoking established cultural values. Editor: Absolutely. And in a photograph, the grayscale renders the texture, the weight of history palpable. Du Camp, in his choice to capture it, is actively documenting not only ancient art but its continued social function— how it’s implicated in a power dynamic that stretches across time. Curator: So true. Seeing how a 19th-century photographer like Du Camp interacts with ancient symbols adds yet another layer to the image. He is bearing witness to a world of sacred kingship, while using a tool of modernity to bring its power into question, simultaneously documenting and potentially dismantling myth. Editor: It pushes us to remember that the “Sacred” isn’t something monolithic or ahistorical; rather, the act of "sacring" or validation is something always actively renegotiated, both in its own time, and across the span of generations of viewers. Curator: Precisely! Looking closer, we are reminded that our experience and cultural memory transforms how these symbols live on. Editor: This piece gives us a rare glimpse into these echoes of a symbolic landscape—ancient rituals echoing across time, revealing power struggles still relevant today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.