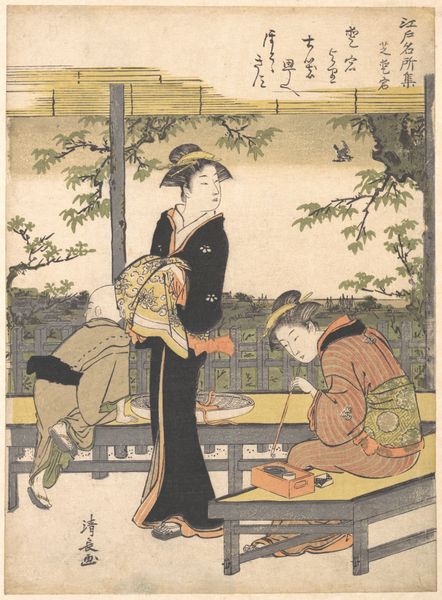

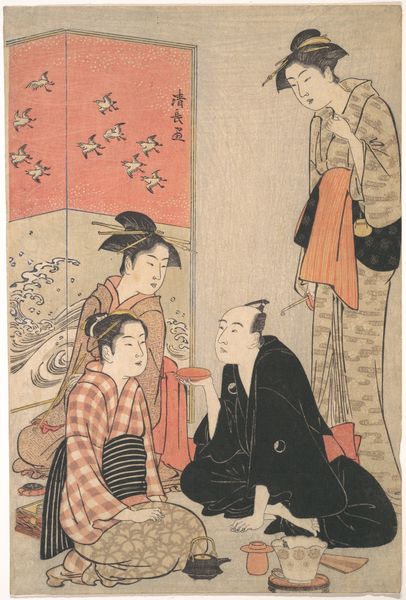

Yushima from the series Scenes of Ten Teahouses (Chamise jikkei) c. 1783

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

line

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 25.6 × 18.3 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, here we have Torii Kiyonaga’s woodblock print, "Yushima from the series Scenes of Ten Teahouses," dating from around 1783. There's something intimate, yet distant, in how the figures are arranged. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: I'm drawn to the process of its creation. Consider the materials – the wood, the inks, the paper – all readily available commodities. Kiyonaga cleverly transforms these materials, implicating consumption and leisurely enjoyment within his meticulous crafting of *ukiyo-e*. What does it mean to represent the "floating world" through mass-produced imagery? Editor: Mass-produced? I thought *ukiyo-e* prints were highly valued? Curator: They are now, certainly, but in their time, these prints weren't high art objects. They were a commodity produced using specific labor processes, bought and sold to be enjoyed in teahouses, for example. That begs the question, who exactly did this art serve and how? Consider also that printmaking is, by definition, a form of reproduction—how might that mass production influence notions of the ‘aura’ of an artwork? Editor: Interesting! So it’s not just the scene depicted, but also the very process of making and circulating it that's key. Seeing the leisure activities framed in the labor-intensive process that is part of its creation makes me rethink how to appreciate the image as more than a representation of the "floating world." Curator: Exactly! By focusing on its means of production and consumption, we reveal the material and social structures that enabled these "scenes" of leisure. What do you make of how it engages or challenges boundaries between "high art" and what we could consider craft production? Editor: It sounds like questioning those boundaries opens a new lens to appreciating art's wider impact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.