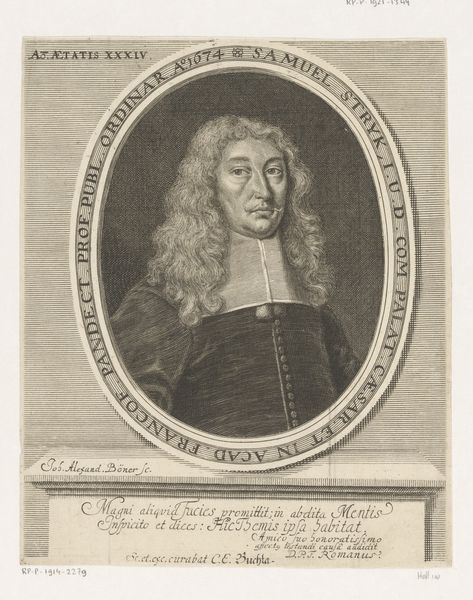

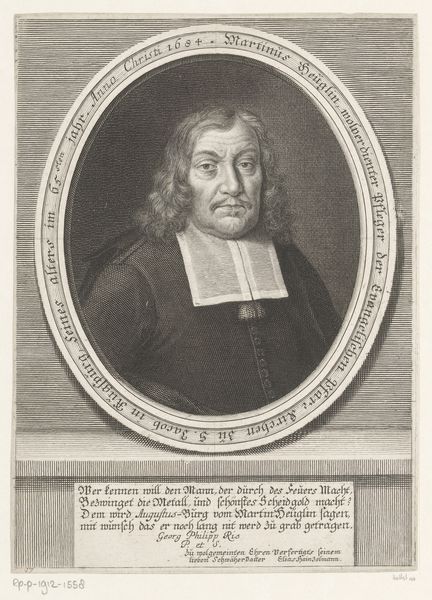

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 194 mm, width 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Artist: Oh, my! The moment my eyes landed on it, a sense of gentle, somber authority just washed over me. It's like staring into the wisdom of ages, captured in monochrome. Curator: Indeed. What we're observing here is a print dating from around 1719 to 1722 titled, “Portret van Samuel Christian Thomae” by Johann Kenckel, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum collection. It showcases Thomae, likely a man of considerable standing. This would have been made with engraving techniques, probably on paper. Considering it's a print, we must reflect upon the reproduction techniques of the day. How many of these were made, where were they distributed and to whom? Artist: Right? It gives you that feeling! The precision in the lines, that calculated distribution of light and shadow... you can tell there’s real skill involved. Looking at it makes me think about how different artists thought back then, you know? How constrained but also liberated by those rules! I bet you someone really skilled labored to create this. It probably took hours and hours! Curator: Yes, exactly! This points to something quite significant—the material conditions and skilled labor necessary for the proliferation of imagery back then. Think of the artisan's studio, the apprenticeship... and consider too, how the act of reproduction itself democratized imagery to a degree, making portraiture available to people outside the elites who could afford painted works. I can imagine people owning these portraits to remind themselves of important historical, religious or scholarly figures. How cool is that!? Artist: True, so many copies made, and so many people gazing at these portraits. That totally takes on a life of its own. You know, what strikes me also is the detail captured, not just in his physical features, but his expression, even those amazing ringlets. To manage to capture that much information, those little facial expression quirks using such minimal resources – amazing! I mean, could *you* do that? Curator: That's precisely the conversation, isn't it? How something shifts from 'craft' to 'art', or, that old, divisive definition. What constitutes art or the material circumstances, as well as its intended use. Take for example, the inscribed words forming the oval around the portrait – adding layers of identification and symbolism, maybe to signal who he was and why he was relevant, his status or position, something meant for wide consumption... But then again... art? Artist: Right. Status. Image. What story they were trying to sell, essentially, like marketing! Anyway... what stays with me is how he seems so human, not distant or deified. There is vulnerability, something really intriguing hiding behind those Baroque curves, isn’t there? Curator: Well, as we draw this to a close, I think focusing on the physical and material dimensions helps ground any aesthetic reactions. What did this say about Samuel, his occupation, or the social standing conveyed by image production like this? So much to see once we start thinking materially about even simple things. Artist: Precisely. For me it's always amazing to be reminded, staring at a piece like this, of the dialogue between then and now and to consider just how connected we all truly are.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.