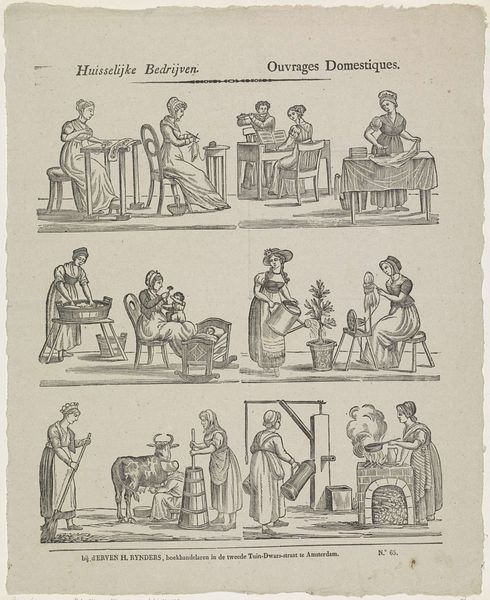

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

folk-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

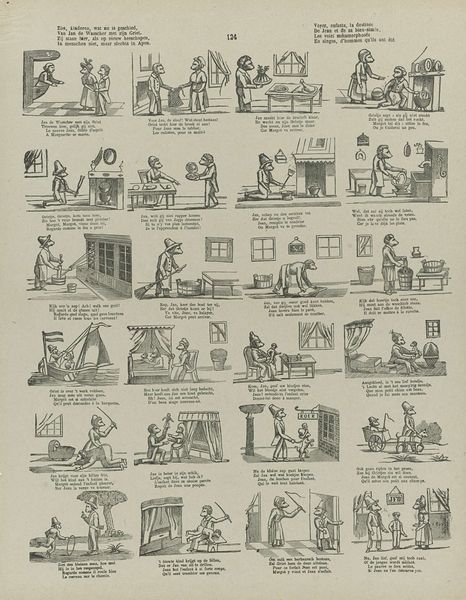

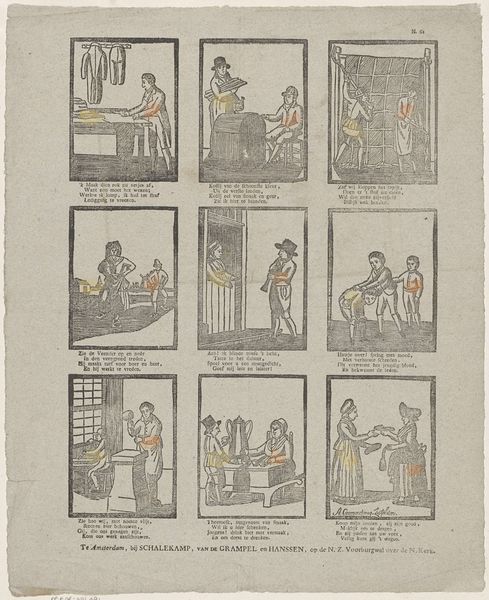

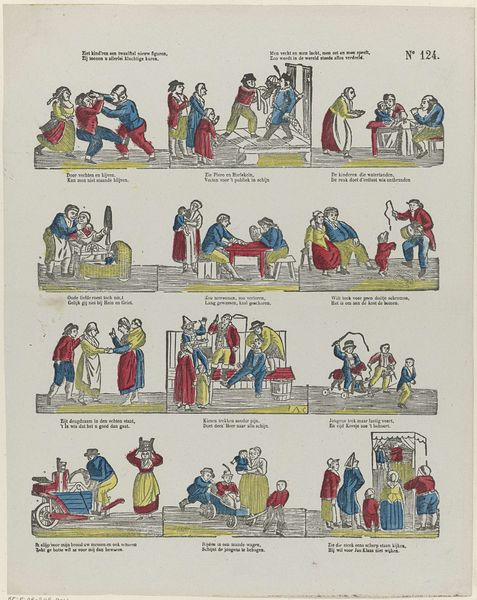

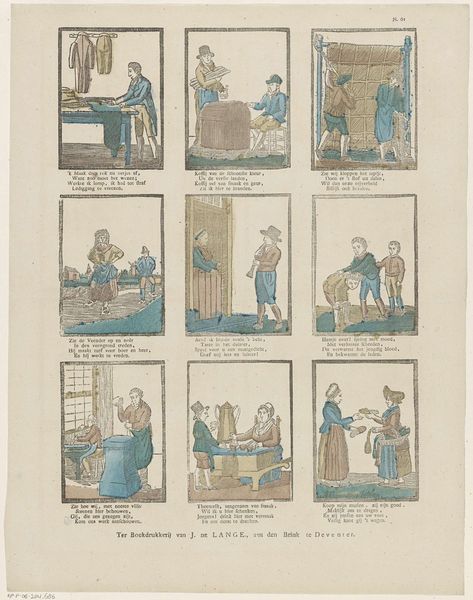

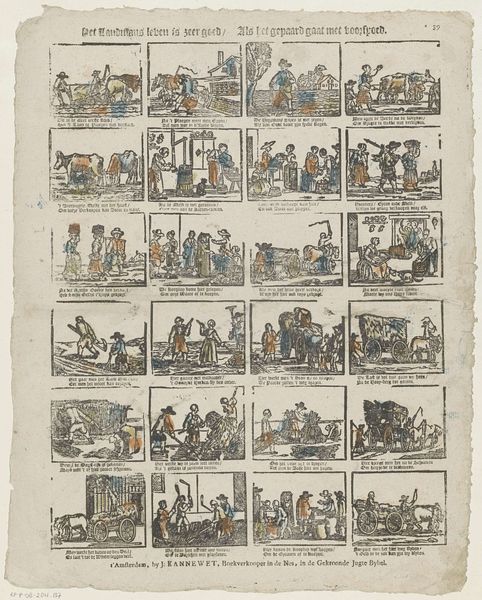

Dimensions: height 431 mm, width 340 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

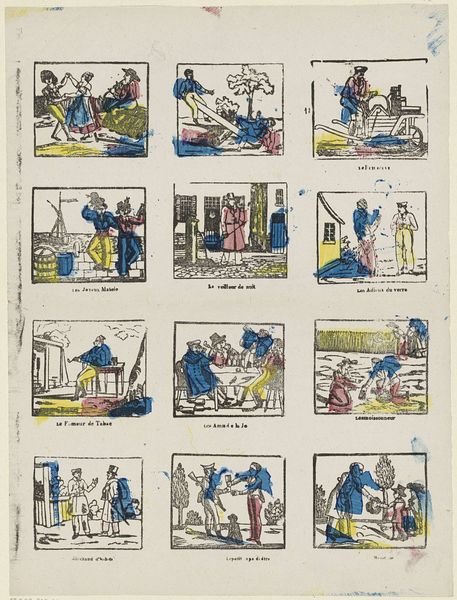

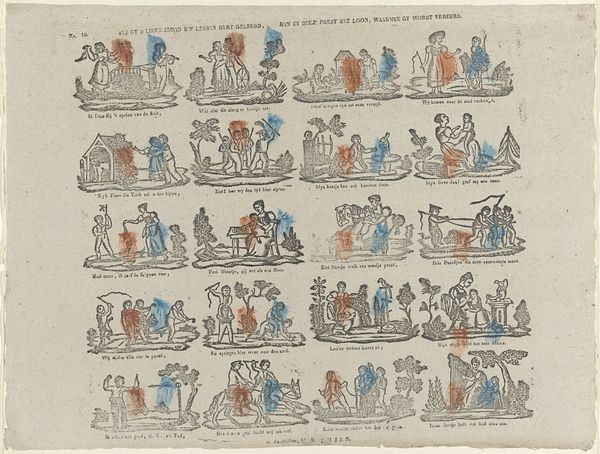

Editor: This is "Zoo wel de stad als 't buiten leven. / Kan ons vermaak en vreugde geven," an engraving by D. Lijsen, created sometime between 1836 and 1849. It feels like a sampler of everyday life, but the repetitive images of women performing labor are a bit unsettling. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It’s unsettling, yes, and it *should* be. This print presents an idealized, but also constricting, vision of women's roles in 19th-century Dutch society. Consider how each vignette depicts domestic tasks - churning butter, cleaning, tending to children. These were considered vital contributions, but what about women's agency outside the home? What voices are absent here? Editor: So, you’re saying it's less about celebrating domesticity and more about highlighting the limitations placed upon women? The inclusion of a water pump scene actually seems empowering in contrast... Curator: Exactly. And what about literacy? The verses accompanying each scene – are these meant for instruction, or something more complex? Notice how even leisure activities, like needlework, are framed as productive labor. This speaks volumes about the cultural expectations of the time. Who created these expectations? Who benefits from them? Editor: I hadn’t considered the verses in that light. It definitely changes my perception. It’s like they’re being given directions, or confined into set roles. Curator: Precisely! What is also striking, and perhaps subtle, is what *isn't* shown here: women engaged in commerce, politics, intellectual pursuits. Does that absence speak louder than what is visibly represented in the engraving? How do we contextualize the lack of agency in their activities? Editor: That is such an interesting point. Thinking about it in terms of the absent narratives makes me reconsider the artist's intentions, too. I wonder if they meant to reveal it all along? Curator: That's the question, isn't it? And that’s precisely where we, as viewers and critics, engage with the work, questioning its surface to unearth the complex layers of history, gender, and power. It allows us to see a common artwork in new and hopefully transformative ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.