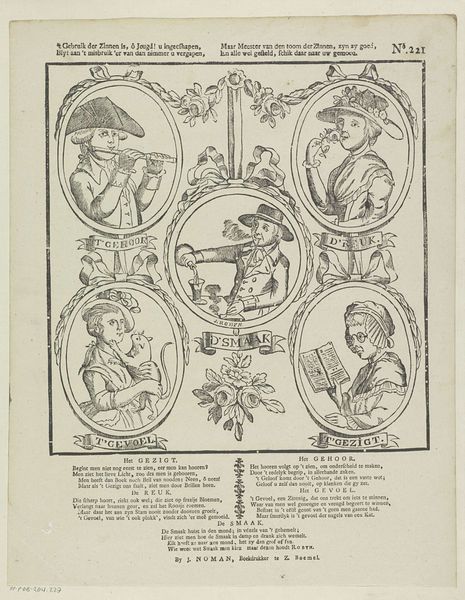

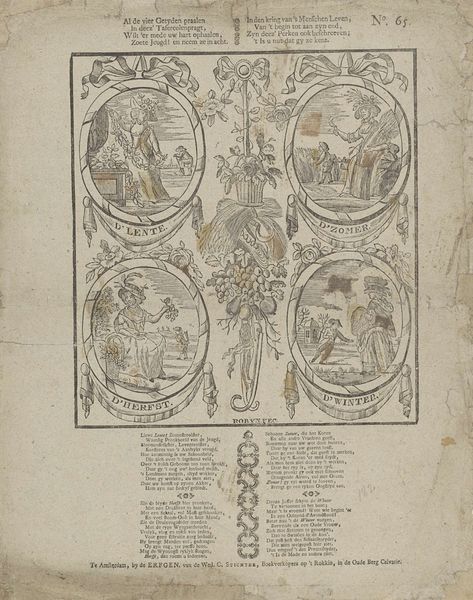

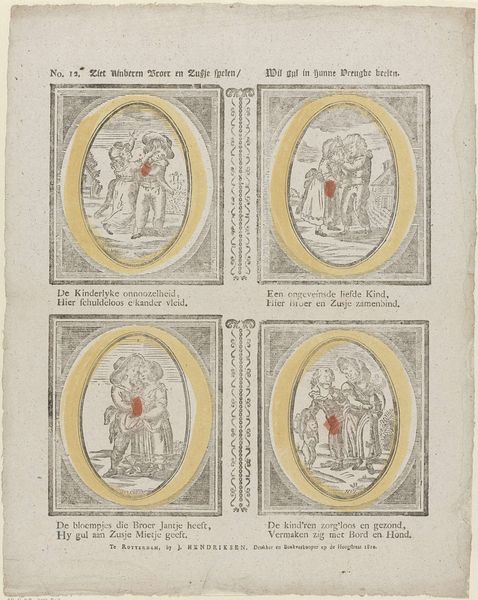

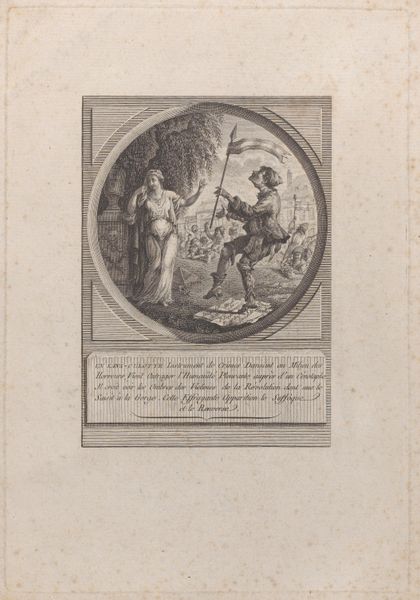

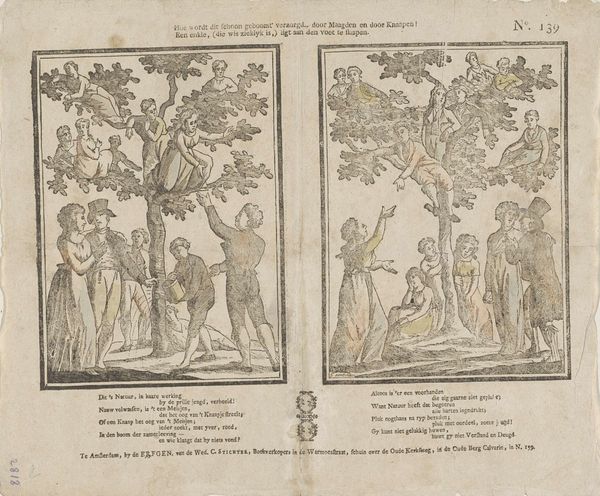

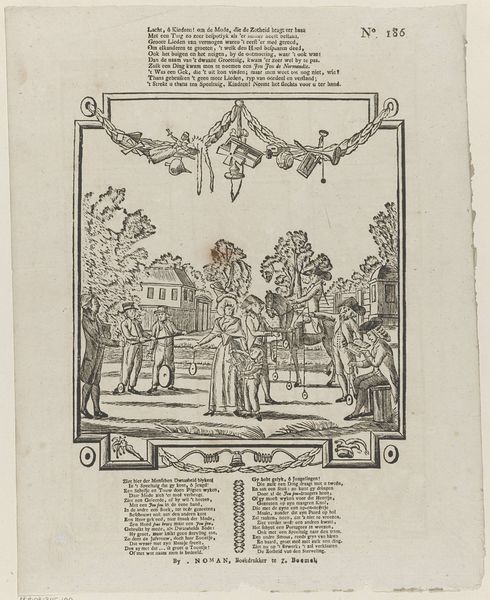

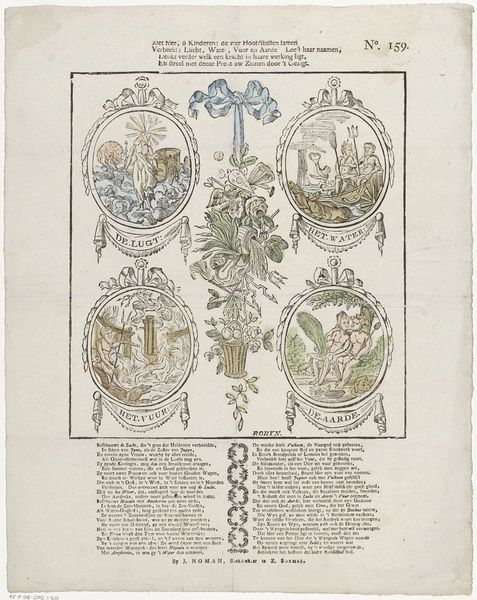

'T gebruik der zinnen is, ô jeugd! u ingeschapen, / Blyf aan 't misbruik 'er van dan nimmer u vergaapen, / Maar meester van den toom der zinnen, zyn zy goed, / En alle wei gesteld, schik daar naar uw gemoed 1715 - 1813

0:00

0:00

jrobyn

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 404 mm, width 328 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

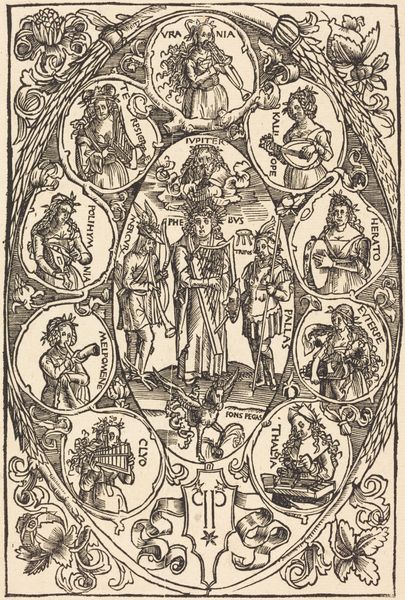

Curator: Let’s talk about this print, “‘T gebruik der zinnen is, ô jeugd! u ingeschapen,” made by J. Robyn between 1715 and 1813. It's an engraving, a relatively accessible medium at the time, depicting the five senses. Editor: It strikes me as didactic, almost like a moral lesson packaged within these delicately rendered scenes. Each vignette, framed within those oval borders, feels both contained and expressive. Curator: Exactly. Robyn utilizes the printing press – a technological marvel then, reliant on skilled labor and material processes – to disseminate a specific ideology. Consider the choice of engraving; it allowed for multiple reproductions, ensuring a wider audience could access its message. The paper itself, likely a rag-based product, speaks to the resources and craft involved in production. Editor: And what is that message, exactly? We see these scenes, each illustrating a different sense, but they are also clearly gendered and classed. Are they not subtly dictating who is allowed to experience pleasure, and how? Curator: You’re right. It's interesting how taste, for example, is portrayed. It isn't simply about physical enjoyment but social practice, access and wealth. The act of consumption itself becomes a performance of social status, reflected in clothes and tableware. This reflects broader issues about production, consumption, and class distinctions in the 18th century. Editor: Indeed. The title itself emphasizes self-control and moderation. It presents a framework for how to navigate pleasure within social norms and power structures, suggesting that mastering one's senses is vital. And given the date, spanning nearly a century of tumultuous social and political changes, the emphasis on individual control can also be read as commentary on the larger social and political order. Curator: I see what you mean. The seemingly simple scenes gain layers of depth when viewed through such lenses. Robyn’s work becomes less about the senses themselves and more about how society shapes their experience and expression. Editor: Absolutely. This piece serves as a reminder that artistic expression is never divorced from its cultural context and the means of its making, each interacting in their own way. It provides unique insights to what kind of visual consumption was popular in the early 1700s.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.