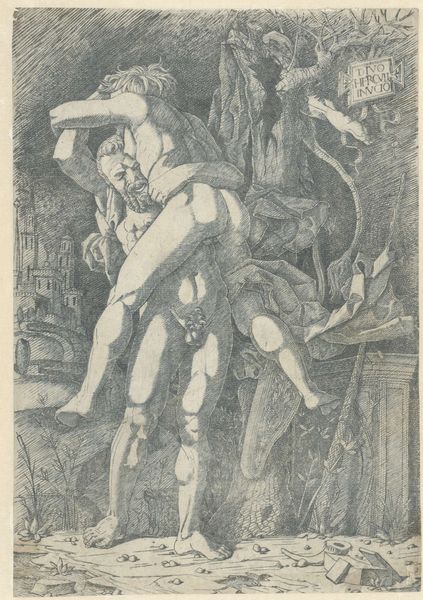

drawing, intaglio, paper, pencil, engraving

#

pencil drawn

#

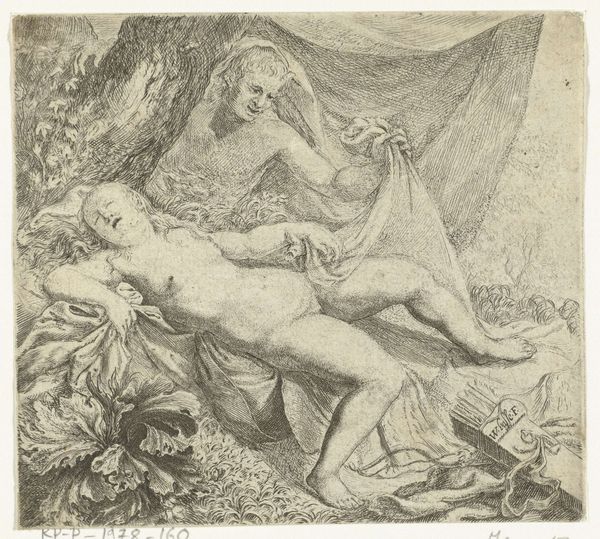

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

intaglio

#

pencil sketch

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

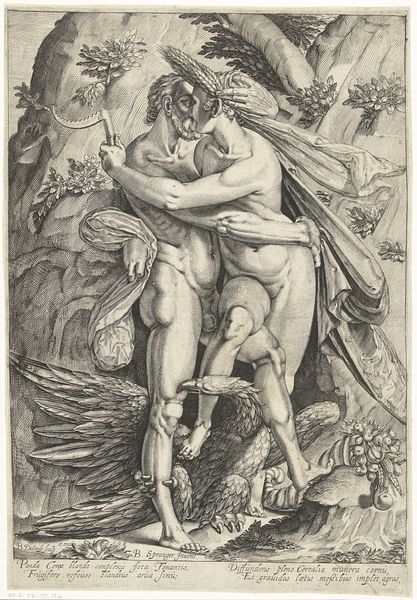

Dimensions: height 335 mm, width 255 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

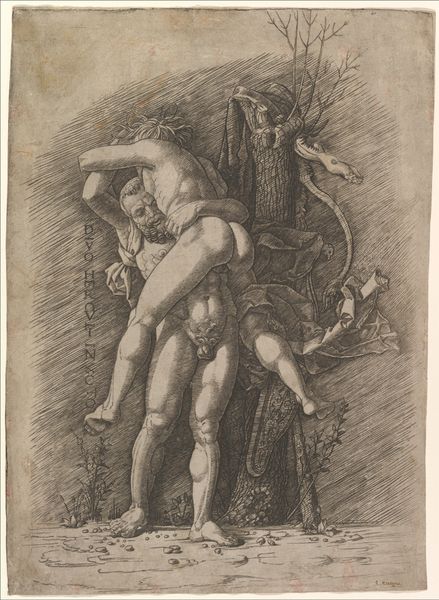

Curator: Here we have "Hercules and Antaeus" by Andrea Mantegna, created somewhere between 1475 and 1499. It’s an engraving printed on paper. Editor: What a wrestle! Raw power on display. The energy is almost unbearable—the intensity of the fight just leaps off the paper. But it’s more than that. Look closer. There’s almost a tenderness amidst all that muscular aggression. It's… strangely beautiful. Curator: Precisely! Mantegna captures a pivotal moment from classical mythology. Antaeus, invincible when touching the earth, is hoisted aloft by Hercules, who’s cutting off his power source. It’s not just a brawl; it’s a symbolic victory of intellect and strategy over brute force. Editor: And notice the engraving style. Such fine lines, almost like scratches on the plate, but they give the figures so much volume. Look at the musculature—the sheer effort of Hercules is visible in every sinew, every bead of nonexistent sweat. Curator: The choice of medium – engraving – also matters. Prints like these circulated widely, popularizing classical themes. Mantegna wasn’t just creating art, but spreading cultural literacy during the Renaissance. He made accessible stories previously confined to the elite. Editor: Accessibility with a heavy dose of idealized masculinity, eh? It's fascinating how the image became iconic—these heroes of yore and those ideals! It's thought-provoking how even now they still carry social connotations. Curator: That’s a good point! These images certainly helped normalize particular physiques and male-dominated narratives. But within the context of 15th-century Europe, it's not a rejection of those classical ideas; it’s a rebirth. Editor: I get that—the historical moment, the desire for cultural and intellectual rebirth—but looking at this now, so long afterward, one sees through that veneer of aspiration into its possible dangers and underlying values. Even masterpieces bear that kind of scrutiny. Curator: That is the nature of looking, is it not? Our perspectives are always evolving with the times. So it invites viewers to engage in that eternal discourse and keep that classical world—in all its richness and problematic nuances—alive. Editor: Absolutely, and it makes me realize how art isn't just a thing of the past. It mirrors our society now, urging us to reflect on what we choose to celebrate—or ignore.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.