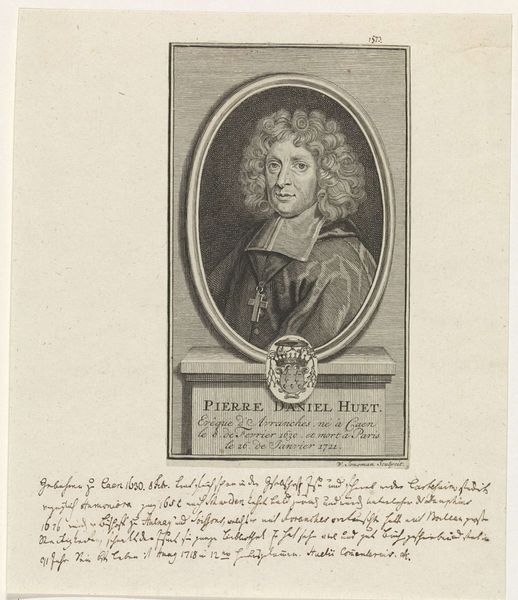

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 345 mm (height) x 249 mm (width) (plademaal)

Curator: Here we see "Sophie Müller," a baroque engraving created between 1670 and 1671 by Albert Haelwegh, currently held at the SMK in Copenhagen. Editor: There’s something unsettling about it. Her eyes seem to bore right through you. Is it the stark contrast of the lines or the tight framing within that oval? It feels quite intense. Curator: The oval format was conventional, hearkening back to classical portrait medallions. Consider the headdress: it subtly evokes a nun’s habit, associating Sophie with piety, even spiritual transcendence. This isn't just a portrait, it is designed to signal virtuous identity. Editor: Perhaps. But it could also represent the limited agency afforded to women of that era. The headdress becomes a symbol of confinement, physically and socially. We’re presented with a controlled image, rather than an authentic representation of her self. Curator: I interpret that she presents herself in the modest fashion associated with a person of status in those times. Observe her stern gaze and the carefully constructed textual cartouche beneath the image itself – Latin verses that amplify her virtues. Haelwegh presents Sophie as more than a likeness; she embodies societal ideals. Editor: And who gets to define those ideals? Look closely, though, her mouth isn’t entirely set. There’s a hint of a downturn, a whisper of resistance to this idealized portrayal perhaps. I believe portraits like these also reveal subtle expressions of dissent in how women had to portray themselves. Curator: I agree that those expressions certainly can appear in these works. Yet, one might suggest these types of portraits played a critical role in shaping the memories and narratives surrounding historical figures of the day. They carry significance beyond just a visual resemblance. Editor: And those memories often serve to uphold existing power structures. Seeing those details allows us to question those power structures as they influence how identities, particularly those of women, have been shaped, consumed, and remembered in art. Curator: That is certainly something I have learned today as well! Editor: Yes, by engaging with art in a critical way, we challenge those silences and create space for a more nuanced and equitable dialogue with the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.