drawing, print, ink

#

drawing

#

ink painting

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

history-painting

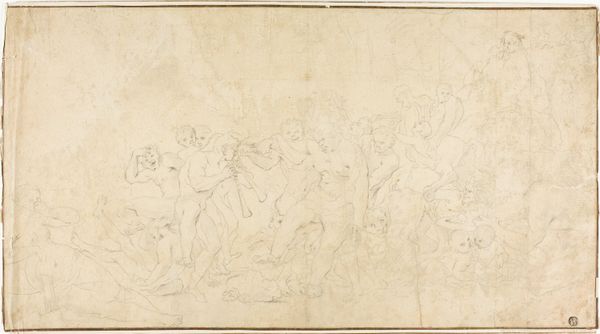

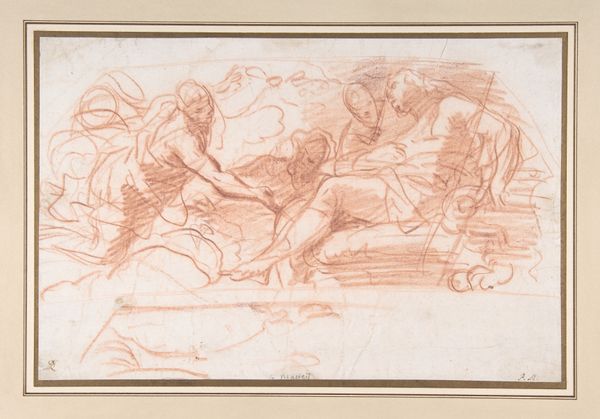

Dimensions: 10-3/4 x 16-5/8 in. (27.3 x 42.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately, this frantic, chaotic energy jumps out at me. It’s unsettling but somehow gripping. Editor: Well, it’s supposed to be. We’re looking at "Massacre of the Innocents," an ink drawing, dating from somewhere between 1500 and 1600 by an anonymous artist. It resides here at the Met. Curator: "Anonymous" speaks volumes, doesn’t it? Almost as if the horror was so ubiquitous, so woven into the social fabric, that attaching a name would be pointless. There's this almost performative masculinity on display as well, men brandishing violence, juxtaposed with the desperate gestures of mothers. It hits hard. Editor: The event itself—Herod's decree to kill all male children in Bethlehem—has been a touchstone throughout art history, usually framed as a political statement or a condemnation of power. Its prevalence speaks to how effectively the Church used these scenes as moral lessons. Curator: Moral lessons rooted in patriarchal violence, one could argue. Who gets to tell this story? How is it told? Where are the midwives, the female healers, the community of women who undoubtedly resisted this atrocity? They’re rendered invisible, the focus funneled onto male aggression and female victimhood. Editor: The artist is highlighting the drama. See the swirling lines, the dynamic composition... there’s almost a Baroque energy, even if the work predates the movement in its maturity. It's clear the artist wants us to feel the sheer terror. What’s especially interesting to me, given this angle, is why the choice of medium. Curator: An ink drawing adds to that feeling of immediacy, doesn’t it? Like a raw, unfiltered outpouring. The hasty lines capture the urgency, the desperation... maybe that’s where some agency lies: not in overt resistance, but in documenting and giving visual form to the trauma. Editor: It forces me to consider its role—not simply as art, but also in the larger cultural dialogue concerning the political uses of imagery and history itself. It's an important but devastatingly complex work, given all those dimensions. Curator: Exactly, and by examining those complexities, we confront the uncomfortable truth that trauma, like this image, continues to shape us. Editor: A harrowing reflection, to be sure, and something that bears remembering as we appreciate this compelling yet troubling work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.