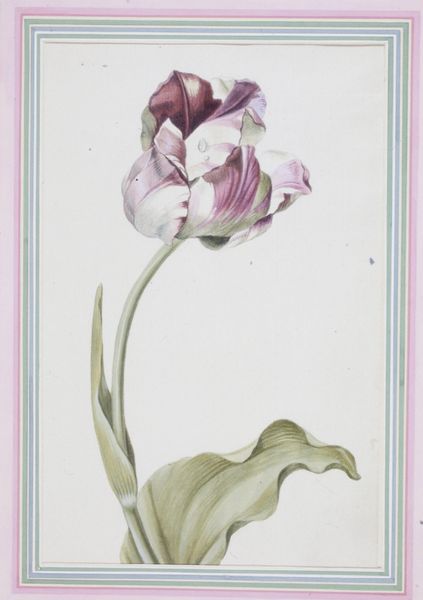

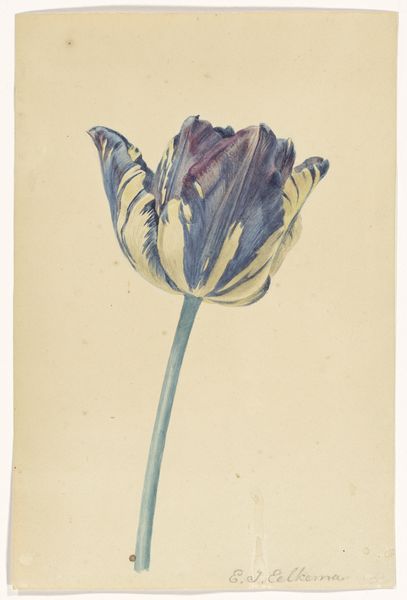

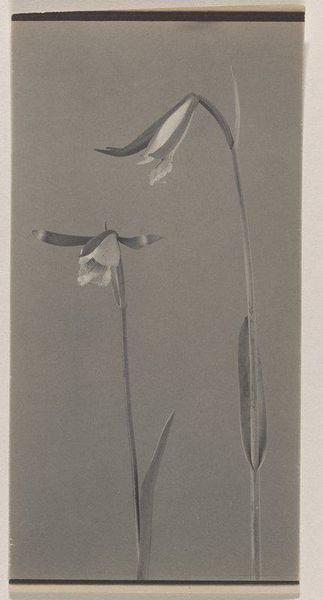

drawing, watercolor

#

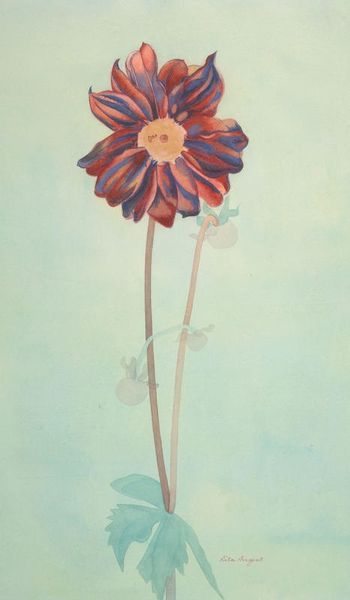

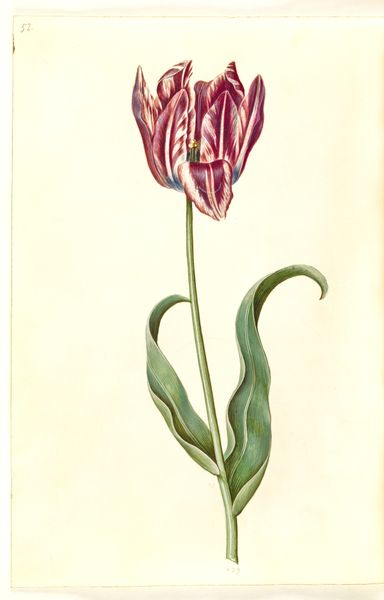

drawing

#

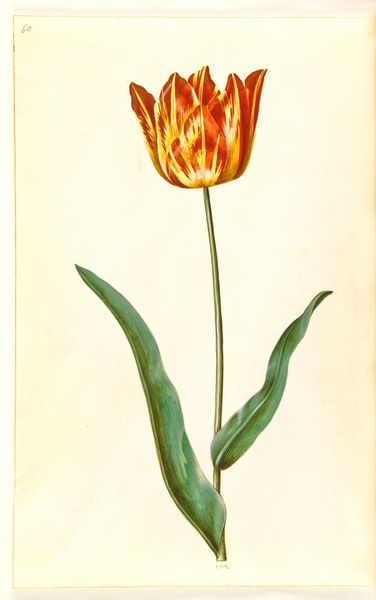

watercolor

#

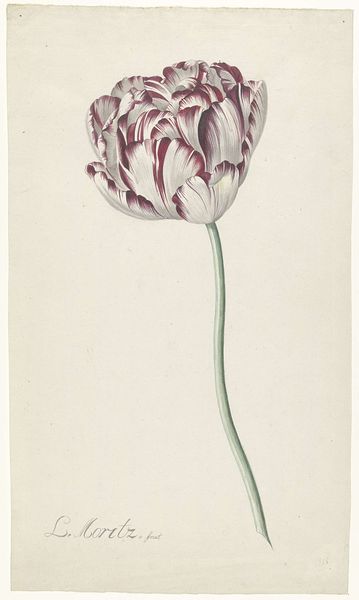

watercolour illustration

#

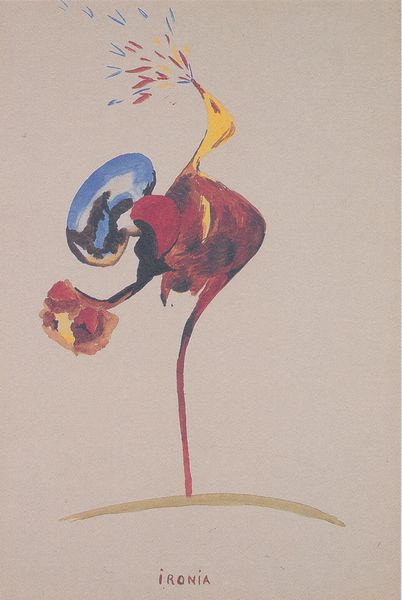

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: 11 1/8 x 4 in. (28.26 x 10.16 cm) (image)12 15/16 x 9 in. (32.86 x 22.86 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Josepha Tusch's watercolour drawing, "Tulipa gesneriana (Didier's Tulip)," created sometime between 1800 and 1815. Editor: The starkness of the bloom against the blank background really catches my eye. It almost feels staged, like a botanical specimen under observation. Curator: And staged it very likely was. During this period, botanical illustration served as a crucial tool for scientific documentation and, increasingly, for display. These were commodities to be carefully documented. Editor: Absolutely. I wonder about the labor involved in producing such a meticulous drawing. The artist's hand, carefully rendering each vein and striation, becomes a form of scientific and artistic craft. And that color palette – the way those watercolour pigments highlight the shape and texture! It points towards a significant level of access to materials and the knowledge required to manipulate them effectively. Curator: That tulip variety, in particular, is telling. The "broken" tulips, with their flame-like patterns, were incredibly fashionable, commanding exorbitant prices during the Tulip Mania era. This drawing immortalizes not just a plant but a cultural and economic phenomenon. Editor: So, this image reflects larger cultural values, anxieties, and even economic realities of its time. The single stem in its relative simplicity is also making a statement. It is almost an icon representing luxury, consumption, and scientific progress. It seems simultaneously a work of scientific study and a status symbol. Curator: Precisely. Museums, royal collections, botanical gardens – they all contributed to shaping the appreciation and understanding of the natural world. Artists like Tusch played a crucial role in mediating that relationship, translating complex information into accessible and aesthetically pleasing images. Editor: Well, thinking about all the hands involved – the growers, the traders, the artists, the patrons – this artwork takes on even greater meaning. It really exemplifies how closely tied art is to the social and material conditions in which it's made. Curator: I find myself wondering how an object like this reshaped visual culture and understanding of the burgeoning market economy. It’s hard not to feel this tulip represents so much more than simply a bloom. Editor: Agreed. Looking at this delicate rendering, it is as much about society as it is about a plant. A tiny picture holding significant historic context.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

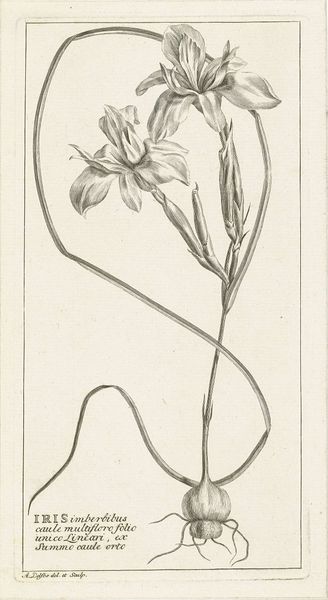

Botanical illustrators working in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries devoted themselves to the medicinal qualities of plants and sought to render plant structure and function as precisely as they could. Later, European explorers brought specimens back from exotic locales, and artists carefully reproduced them for an audience fascinated by new discoveries. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists had shifted their emphasis from scientific illustration to the innate beauty of the plant or flower. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts is fortunate to possess an impressive collection of more than 2,000 botanical prints and drawings.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.