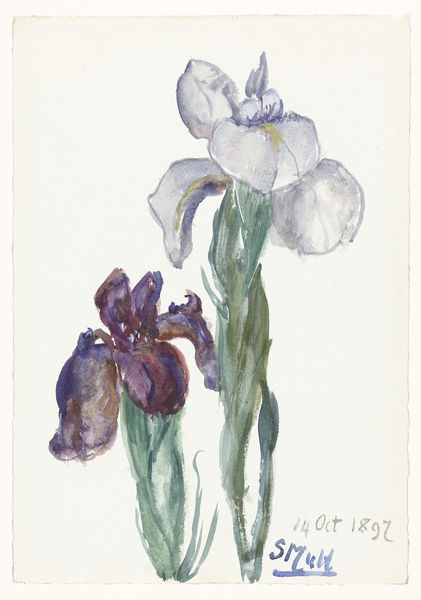

drawing, painting, watercolor

#

drawing

#

painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

realism

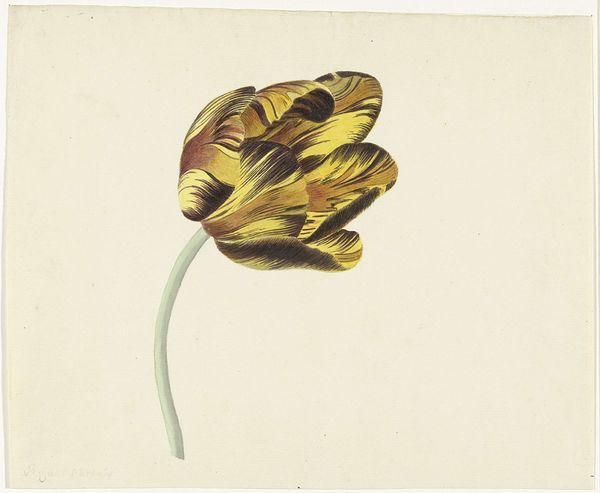

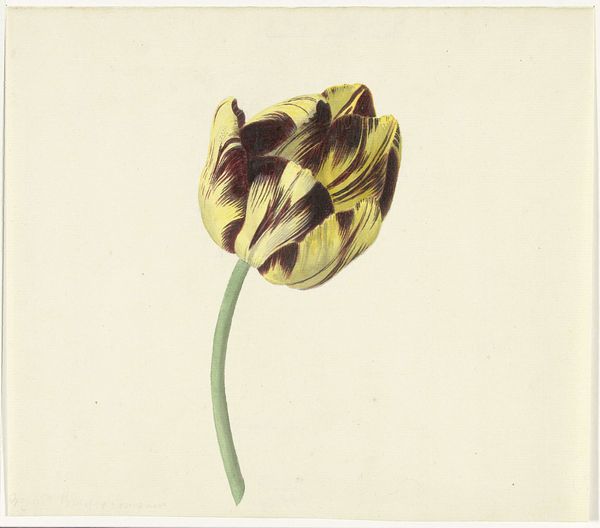

Dimensions: 13 3/4 x 8 5/8 in. (34.93 x 21.91 cm) (image)14 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (36.2 x 25.15 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

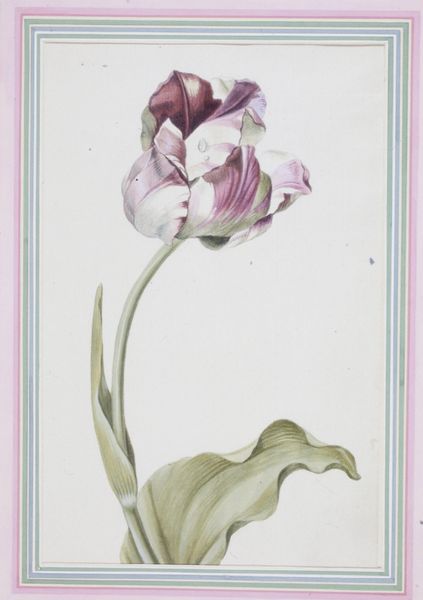

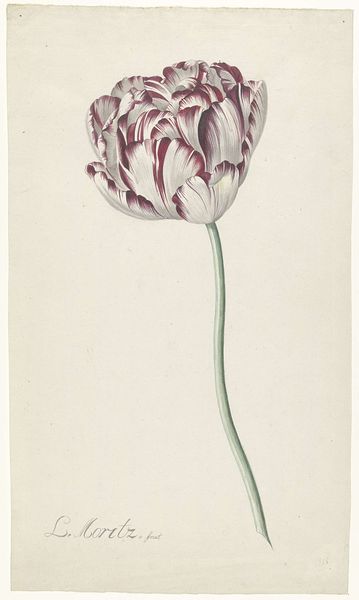

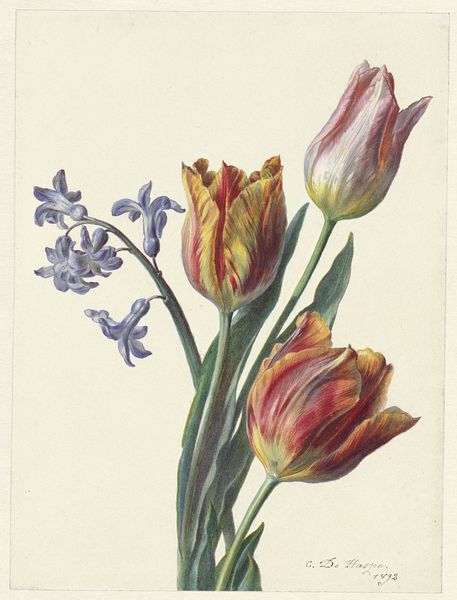

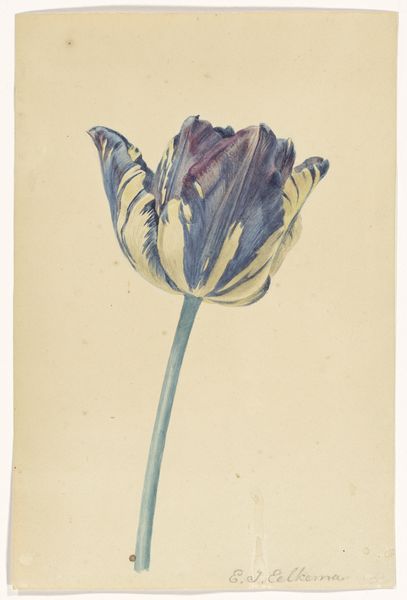

Editor: This is "Tulipa gesneriana (Didier's Tulip)," a watercolor drawing and painting from 1815. It looks so delicate, almost like a botanical illustration, but there's also a sort of melancholy in the drooping form of the tulips. What stands out to you most about this piece? Curator: Well, the tulip itself carries immense symbolic weight. In the 17th century, particularly in Holland, tulips weren't just flowers, they were a symbol of wealth and status, leading to the infamous Tulip Mania. A single bulb could cost more than a house! Editor: Wow, I didn’t know that! So is this painting referencing that era? Curator: Perhaps not directly, but the echo remains. By 1815, the tulip craze was long over, but the flower still held a certain allure. Notice the almost excessive detail, each stripe on the petals rendered with precision. What do you think this might signify in the context of Romanticism, which favored emotionality and the sublime? Editor: Maybe it's about capturing the beauty of something fleeting, or even unattainable, like the height of Tulip Mania. There's a real sense of realism, but a flower like this seems almost too perfect. Curator: Precisely. Consider also the colour palette - those muted purples and whites. They’re elegant, but also convey a sense of fading glory, perhaps mirroring the ephemeral nature of beauty and wealth. What does this imply to us in a contemporary perspective? Editor: It’s like a reminder that beauty is transient, that even things we value highly can lose their luster over time. Seeing it this way makes me appreciate its quiet elegance even more. Curator: Exactly. Through visual symbols, it speaks of both individual passions and wider historical movements, revealing how even simple objects like flowers can embody powerful emotions and meanings across time.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Botanical illustrators working in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries devoted themselves to the medicinal qualities of plants and sought to render plant structure and function as precisely as they could. Later, European explorers brought specimens back from exotic locales, and artists carefully reproduced them for an audience fascinated by new discoveries. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists had shifted their emphasis from scientific illustration to the innate beauty of the plant or flower. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts is fortunate to possess an impressive collection of more than 2,000 botanical prints and drawings.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.