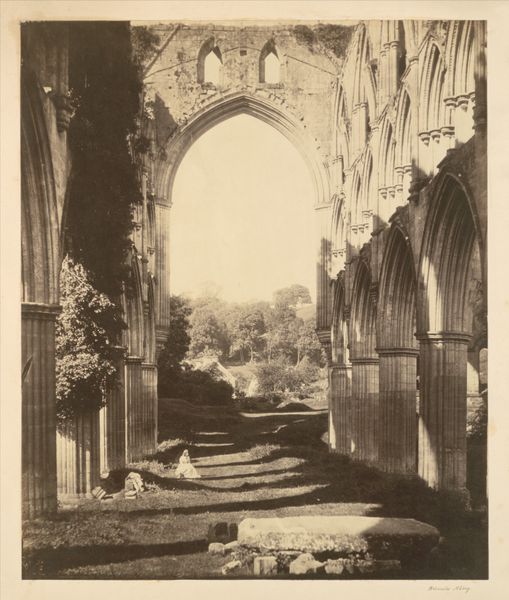

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 242 mm, height 455 mm, width 355 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

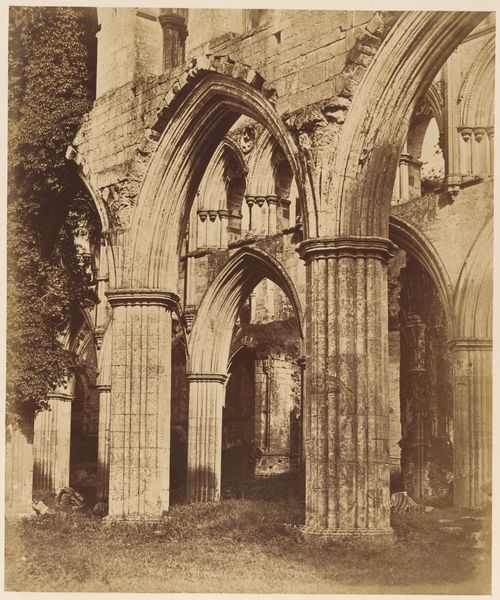

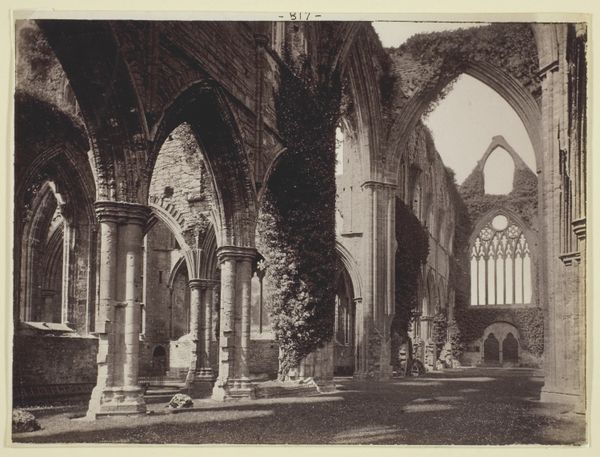

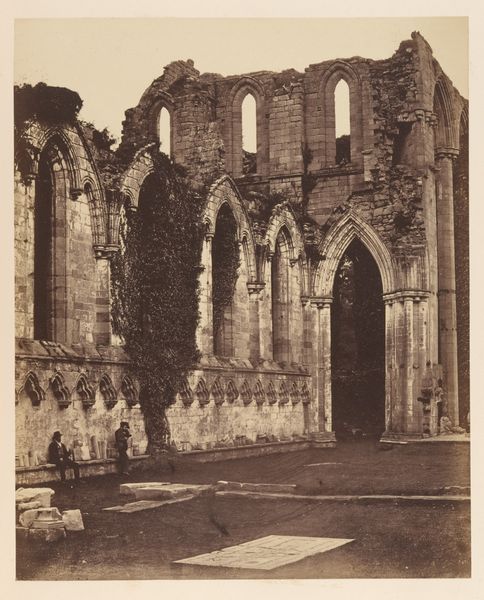

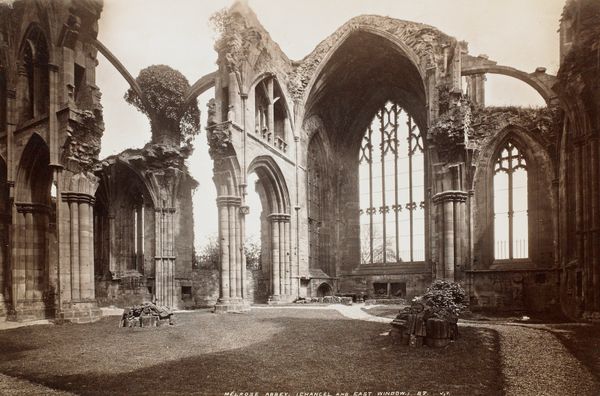

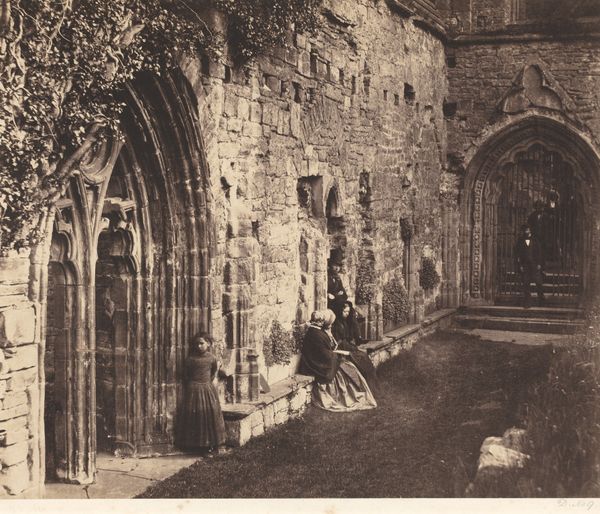

Curator: Here we have an anonymous gelatin-silver print from around 1858 to 1861, titled Ruïne van de Abdij van Tintern—Ruins of Tintern Abbey. What's your initial take? Editor: It feels melancholy, almost romantic in a way. The high contrast and the sheer size of the ruins are quite striking. I’m immediately drawn to the surface of the stone and the light as it glances off the heavy materiality of the aging abbey. Curator: Absolutely. The work depicts Tintern Abbey in Wales, a site laden with historical and cultural significance. Consider the socio-political backdrop: the rise of Romanticism and the fascination with medieval ruins as symbols of the past, of lost grandeur. The act of photographing such a site becomes a statement in itself. Editor: Indeed. The photograph emphasizes not only the visual spectacle, but also the physical decay and transformation of materials over time. The vines are consuming it! Think about the labour involved in quarrying, shaping, and erecting this structure centuries ago, versus the relatively easy production of the photographic print capturing its current state. Curator: A powerful point about the ease of replication and access in the 19th century. Photography democratized images of places previously only accessible to the wealthy elite or those able to make a pilgrimage. This photograph allowed viewers to engage with history from afar. Editor: It also highlights the tension between nature and human creation. The architecture signifies human labor and ambition, but the rampant plant life reclaims the site. This juxtaposition underscores themes of time, impermanence, and the cycle of decay. Curator: The choice of the gelatin-silver print, a relatively new technology then, contributes to the aesthetic. It gives a certain clarity, but it also accentuates the contrast and the play of light, as you pointed out earlier. The photograph romanticizes the past while simultaneously presenting it in a modern, accessible format. It begs questions about what societies choose to preserve, and for whom. Editor: Precisely, and through careful study, one sees this photographic process and the resulting print are not so far removed from architecture or sculpture, labor-wise; there is craftsmanship, design, and chemical artistry inherent in making a gelatin-silver print, one that must bear weather like the aging abbey. This photograph creates more questions than answers, making us think about the intersection of the past, present, and how we perceive and value both labor and nature.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.