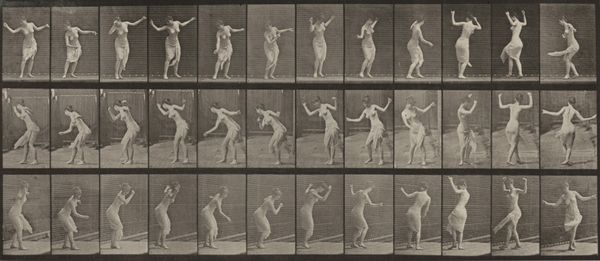

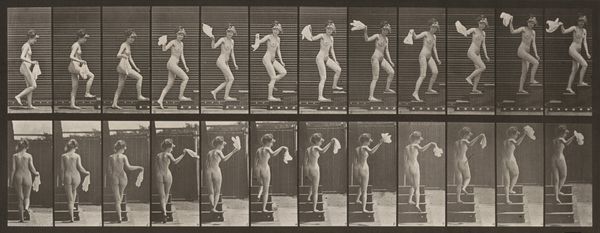

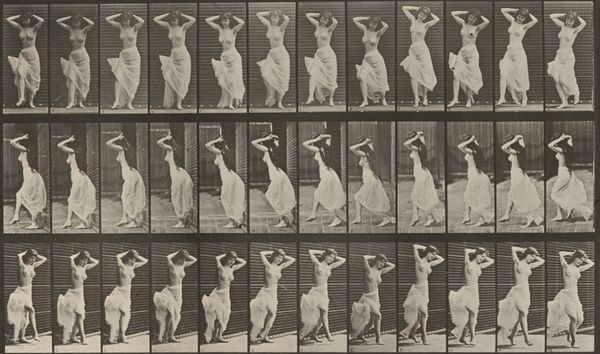

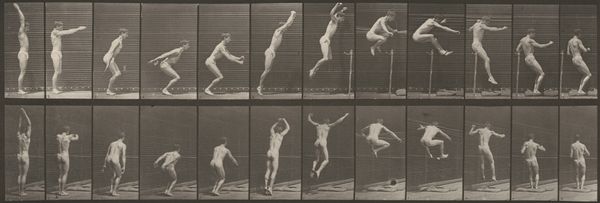

Plate Number 175. Crossing brook on stepping-stones with a fishing pole and can 1887

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

kinetic-art

# print

#

impressionism

#

figuration

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

nude

Dimensions: image: 17.2 × 42.1 cm (6 3/4 × 16 9/16 in.) sheet: 47.5 × 60.1 cm (18 11/16 × 23 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

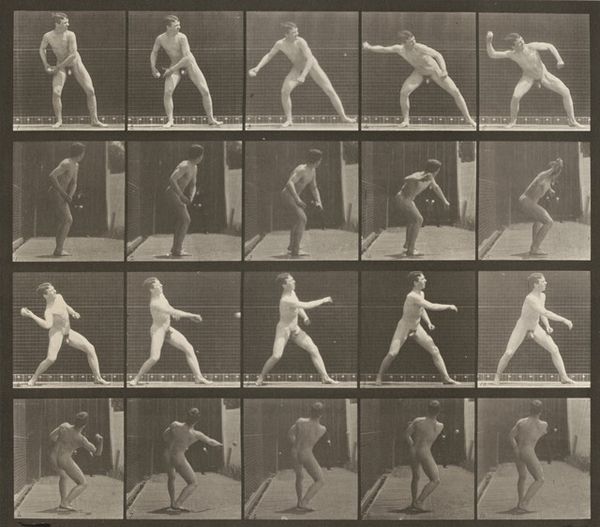

Editor: Here we have Eadweard Muybridge's "Plate Number 175. Crossing brook on stepping-stones with a fishing pole and can," a gelatin silver print from 1887. The grid-like composition immediately grabs you, with its stop-motion sequence of a woman in motion. How do we contextualize this work within the broader scope of art and its development? Curator: Well, it's crucial to consider the societal context. Muybridge was working in an era fascinated by scientific advancement. Photography, particularly the ability to capture motion, became a powerful tool, almost a public spectacle. His work satisfied both scientific curiosity and a growing public appetite for visual realism. We have to ask ourselves, what power structures enabled Muybridge to produce this type of imagery? Editor: So, it's about more than just capturing movement; it’s a demonstration of photographic power itself? How did that impact perceptions of the body? Curator: Precisely! Consider how institutions of science and art intersect here. Muybridge's studies contributed to scientific understanding, yet also fueled artistic explorations of form. The female nude, especially, enters a new public realm. The very act of dissection becomes reframed as documentation of human movement in public imagination, while simultaneously reasserting the power of institutions—the scientific gaze, if you will—over the observed. Is she presented as an individual or as an object of study? Editor: I see what you mean. It walks this tightrope between scientific documentation and, possibly, a kind of objectification fueled by existing societal norms. Do you think his work challenged or reinforced those norms? Curator: I think it perpetuated them even as it expanded knowledge. What begins as scientific inquiry gets quickly caught up in spectacle and established structures. It becomes intertwined with the evolving power dynamics of the late 19th century, when social hierarchies significantly influenced who was seen, how they were seen, and who did the seeing. So it asks a very contemporary question of “who gets to look?” Editor: It's interesting to consider how this blend of science and art, under these very specific conditions, really shaped not just artistic styles but also the social landscape of the time. Thanks for providing that crucial perspective! Curator: Of course! It's essential to acknowledge the complex relationship between artistic production, societal forces, and the historical narratives we construct around art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.