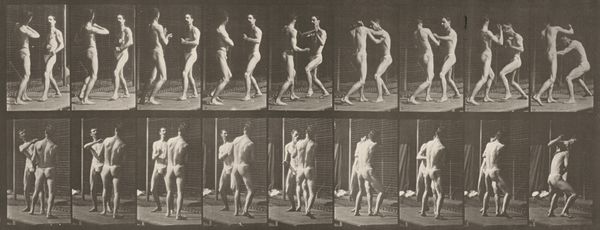

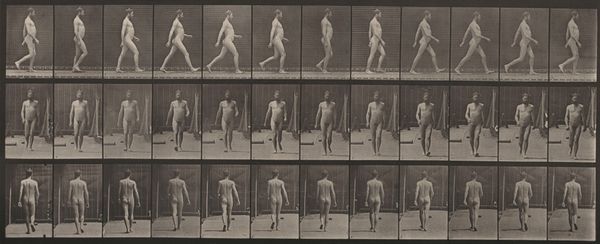

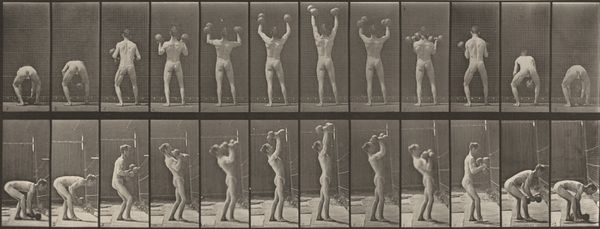

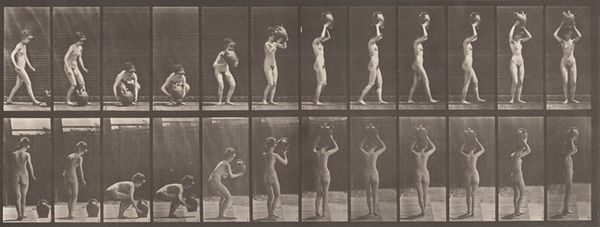

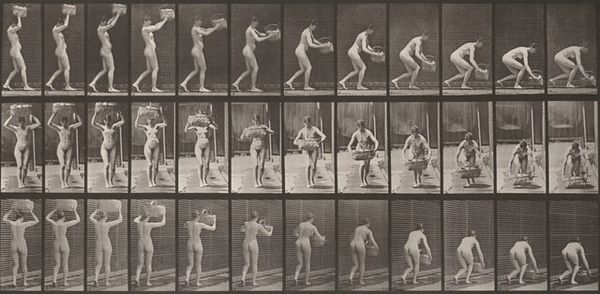

Plate Number 378. Blacksmith, hammering on anvil with two hands 1887

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

kinetic-art

# print

#

impressionism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: image: 19.6 × 38.6 cm (7 11/16 × 15 3/16 in.) sheet: 48.3 × 61.3 cm (19 × 24 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

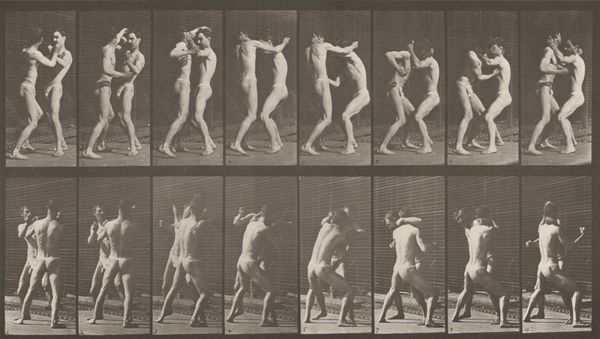

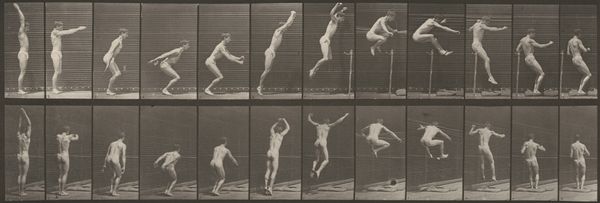

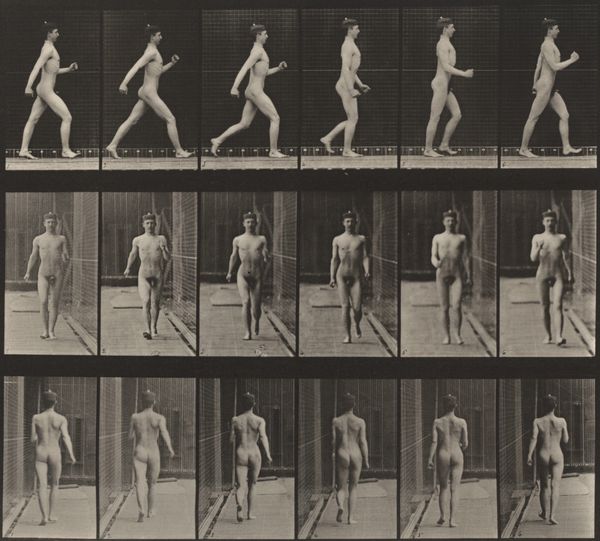

Editor: So, this is Eadweard Muybridge's "Plate Number 378. Blacksmith, hammering on anvil with two hands," a gelatin-silver print from 1887. What immediately strikes me is the almost scientific way he's broken down this very physical labor. What do you make of it? Curator: I see a crucial documentation of industrial labor at a turning point. Photography, specifically Muybridge’s pioneering work, enters the realm of mass production here. Before, art was about depicting labor; now, it’s actively part of its analysis, even its potential replacement. Notice how the body, rendered as a sequence, is dissected into units of action – ripe for optimization within the factory. Editor: Interesting. So, the photograph itself becomes a tool of production, almost? Do you think the choice of the nude figure is significant in this context? Curator: Absolutely. The nude figure is a classical trope, but here, removed from idealization. By stripping him bare, Muybridge highlights the mechanics of the body performing labor, laying bare the physical exertion and implicitly asking us to consider its value in a rapidly industrializing society. It makes one consider how laboring bodies, like materials, are shaped by economic forces. How do the print’s materials influence your understanding? Editor: That's fascinating. Knowing it’s a gelatin-silver print, a reproducible medium, further emphasizes that idea of deconstruction and mass production you mentioned. I never thought about photography being so closely linked to labor before. Curator: Indeed, we must acknowledge photography not merely as a reflector, but as an active participant in the socio-economic processes it captures. And labor, like any medium, gains expression under determined conditions of production. It becomes, ironically, art itself. Editor: That makes so much sense! This image is far more complex than I initially perceived. Thank you for sharing that insight!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.