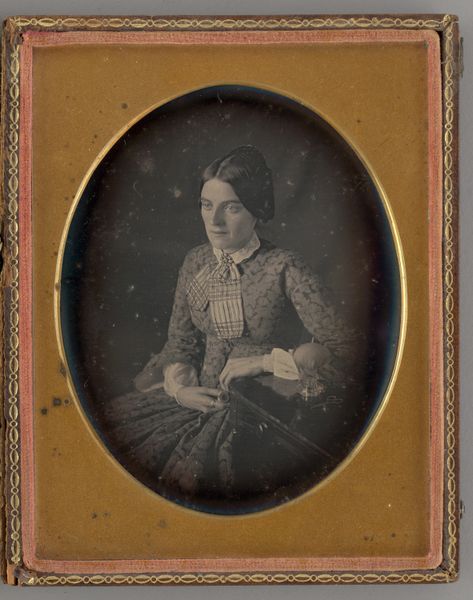

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

sculpture

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

united-states

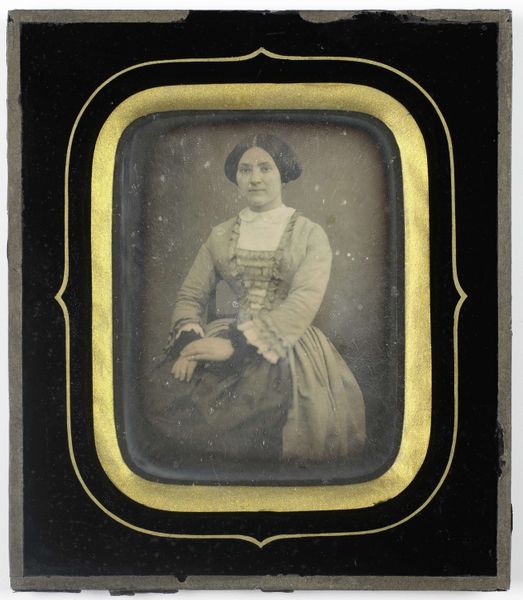

Dimensions: 8 × 7.1 cm (3 1/4 × 2 3/4 in., plate); 18.6 × 8.4 × 1.2 cm (open case); 9.3 × 8.4 × 1.8 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So here we have "Untitled (Portrait of a Woman)," a daguerreotype from 1840 by Huddleston & Co. at the Art Institute of Chicago. I'm struck by how the image itself, almost a ghostly silver, emphasizes the material process. How do we even begin to unpack this object? Curator: A good start is thinking about the daguerreotype itself as a commodity. The silver-plated copper, the mercury vapor used in development—consider the social relations embedded in the extraction, production, and distribution of these materials. It's not just about capturing a likeness, it’s about industry. How does that sit with you? Editor: That’s a very different angle than just considering its aesthetic value. To think about this image in terms of 1840's supply chains makes me wonder: Who had access to such a cutting-edge—and likely expensive—technology? Did it impact artistic patronage at that time? Curator: Exactly! These early photographic studios became new sites of labor. Who were the workers preparing the plates, operating the cameras, and hand-tinting the final images? Consider their training, their wages, and their position in a rapidly changing visual economy. Can we even discuss it as portraiture if it wasn't painted? Editor: That’s fascinating. It forces me to reconsider who is represented and how photography contributed to an industrial form of artistic production and how it challenged portraiture practices as painting started doing other things... Thank you for helping me look deeper into the subject matter of this image. Curator: Of course. The materiality of art opens doors to so many stories beyond just aesthetics and attribution.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.