Copyright: Public Domain

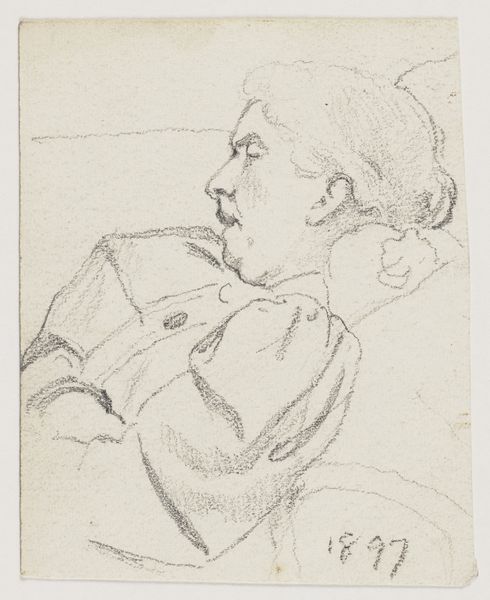

Editor: Here we have Otto Scholderer's pencil drawing, "Luise Scholderer im Profil nach rechts," created in 1897. It’s a delicate sketch on paper, and what strikes me immediately is its quiet intimacy. What do you see in this piece, beyond a simple portrait? Curator: It is far more than just a likeness, isn't it? Looking at Luise’s profile, rendered so softly, I'm struck by the vulnerability Scholderer captures. Considering this was created in 1897, a period marked by rigid social expectations and defined gender roles, the portrait becomes quietly subversive. Luise, likely the artist’s wife, is not presented as an object of idealized beauty but as an individual, contemplating her inner world. The slight droop of her eyelid, the subtle suggestion of a double chin – these imperfections humanize her. Editor: That’s fascinating. So, you're suggesting that by avoiding idealization, Scholderer might be making a statement? Curator: Precisely. The choice of pencil, a readily accessible and unassuming medium, further democratizes the image. This wasn't intended for public display but rather a private act of observation, a tender acknowledgment of a woman's lived experience. The fact that the date is inscribed suggests that it might be like a diary entry for the artist, too. It invites questions about how we value art that portrays ordinary women with an objective lens. In a world still battling inequalities, it remains deeply relevant, no? Editor: Absolutely. I hadn’t considered the medium itself as part of the message. Thank you. I'll never look at "simple" portraits the same way again. Curator: That’s the beauty of art, isn’t it? To constantly reconsider our preconceptions and to open dialogues about who is seen, how, and why.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.