Copyright: Public Domain

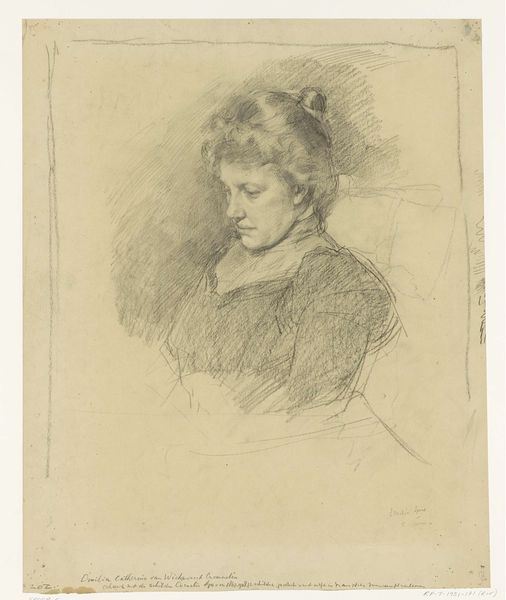

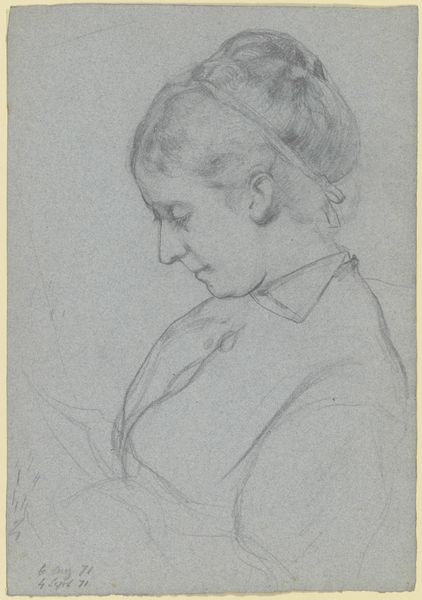

Editor: Here we have Otto Scholderer's "Luise Scholderer, im Lehnstuhl sitzend," created around 1871. It’s a delicate pencil drawing on paper, housed here at the Städel Museum. It feels very intimate, like a captured moment. What do you see in this portrait? Curator: I see a layering of social contexts embedded in the very act of portraiture during this period. The sitter's pose, the clothing... all these elements were carefully constructed to convey a particular message about her social standing and role within the family. Editor: So, it's not just a likeness, but a statement? Curator: Precisely! Consider the subtle way she averts her gaze. Is that a demure gesture, representative of the limited agency afforded to women during this era? How do contemporary feminist theories help us interpret Luise's apparent passivity, or does that impose modern thought onto a historic piece? Editor: It’s a very contained portrait, you’re right. The limited palette amplifies that reserve. Was it typical to capture women in such restrained portrayals at the time? Curator: That's a crucial question. Realism as a movement was beginning to grapple with representing the world as it was, but it was filtered through the lens of societal expectations. And of course, gender norms were central to that filtering process. Did realism, in fact, contribute to solidifying constraints by only mirroring, or was it reflecting actual society and initiating its critique? How might we read this image against broader trends in portraiture of the era, and of women's representation at large? Editor: I never considered that the “real” itself could reinforce certain norms. Curator: Absolutely. And remember, art can be both a mirror and a hammer. Hopefully you see what I mean by initiating the dialogue! Editor: I do. Thanks. That definitely makes me consider portraiture, and realism, much differently now!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.