print, ink, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

caricature

#

asian-art

#

caricature

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

figuration

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: 14 1/8 × 10 1/8 in. (35.88 × 25.72 cm) (sheet, vertical ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

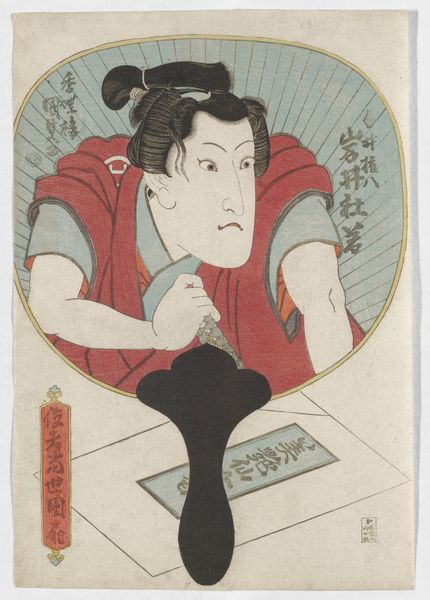

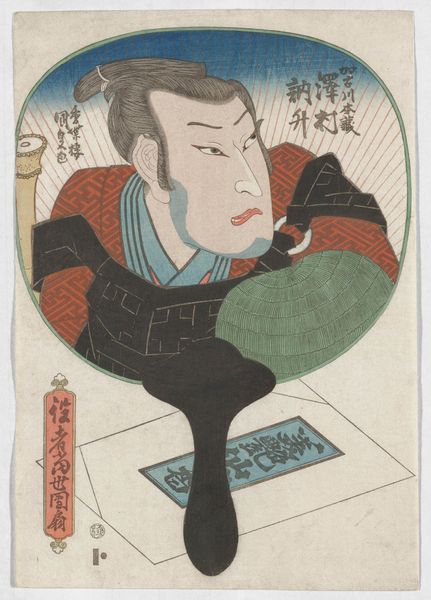

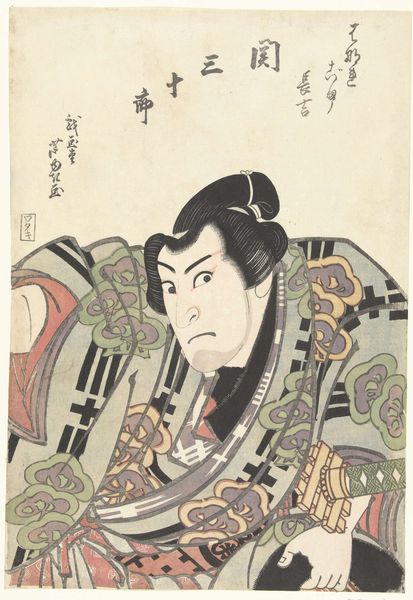

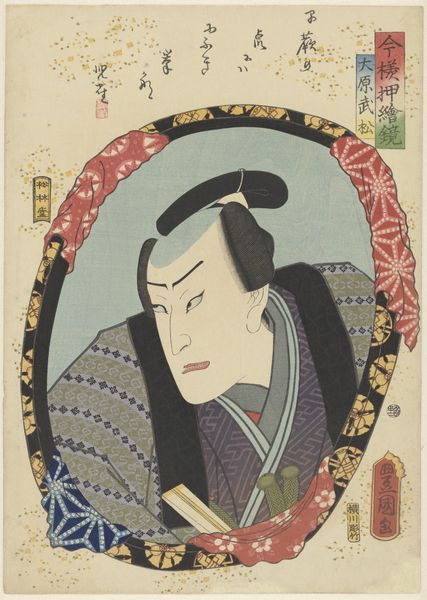

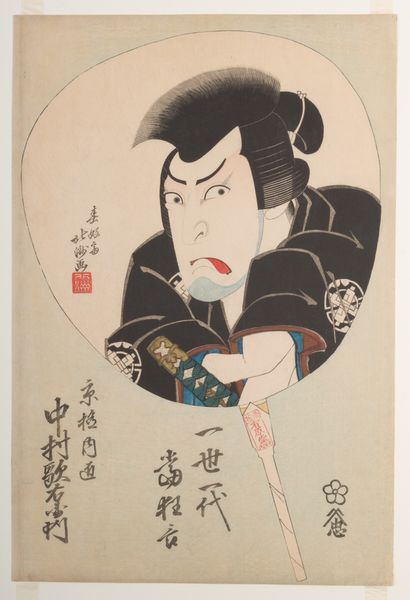

Curator: My initial reaction is a study in contrasts! The sharp lines and defined planes create a dramatic effect that highlights the figure’s forceful character. Editor: Here we have Utagawa Kunisada's woodblock print from around 1833, titled "Actor Matsumoto Kōshirō V as Banzui Chōbei". It's currently part of the collection at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Curator: Given the historical context of ukiyo-e, its existence challenges notions of artistic production being inherently unique and inaccessible. How does this reproducibility affect perceptions of class and culture, especially during its creation and in today's re-contextualization? Editor: Well, the material choices themselves - the wood, the ink, the paper, of course, speak to that. Ukiyo-e prints like these were designed for a mass audience, fueled by the rise of a merchant class in Japan and their disposable income. This particular print also provides clues: Kunisada has represented Matsumoto Kōshirō V, a popular actor, in the role of Banzui Chōbei, a historical figure associated with commoner resistance. The creation and circulation of ukiyo-e gave access to a type of imagery and the potential for discourse surrounding societal change in an environment where few commoners could ever access "high art." Curator: Exactly! The interplay between the actor, the role he portrays, and the print itself complicates hierarchical power structures within Edo-period society. I would even say it actively reshapes and reframes ideas of morality in Japan. The gaze, specifically the expression given to the actor, evokes a feeling of suspicion. Editor: I wonder how the labor process, where the artist often wasn't the craftsman physically creating the print, affected Kunisada’s artistic intentions. It forces us to acknowledge those who remained largely anonymous. Consider how different this is from a singular painting made by one person! Curator: The tension is precisely within that contrast. And in the relationship between mass production and subjecthood, and in turn, access, gender and class during Japan’s Edo-Period. Editor: Understanding Kunisada’s art in this way highlights how material practices can directly intervene in historical power dynamics. Curator: It’s a fantastic entry point for discussing art’s societal and political role, don't you think? Editor: Definitely. Examining these works helps reveal art’s often unseen connections to material culture and everyday labor.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Related to the plav "Mitsu ichō gozonji no Edo-zome" 三銀杏御存地染, performed at the Nakamura Theater, 1833, fifth month. Utagawa Kunisada’s bust portraits from the 1820s and 1830s typically show actors against a plain background accompanied by poems composed by the portrayed actors. Here, the portrait is fan shaped, allowing the image to be cut out and affixed to an actual fan. This series is also an early example of product placement, as a packet of Bien Senjokō face powder appears at the bottom of each print. It seems that the prints were delivered together with the powder or that the producer of the powder paid for some of the production costs of the print.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.