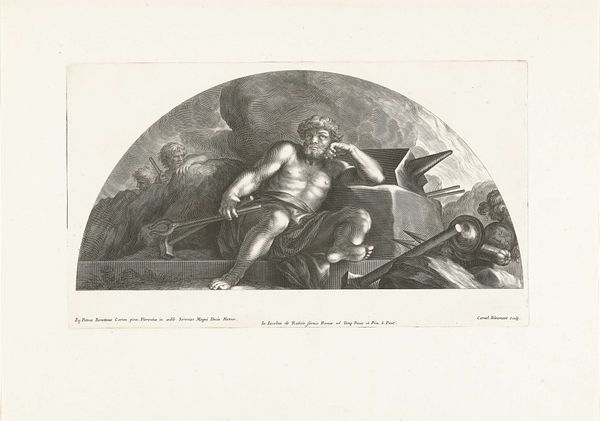

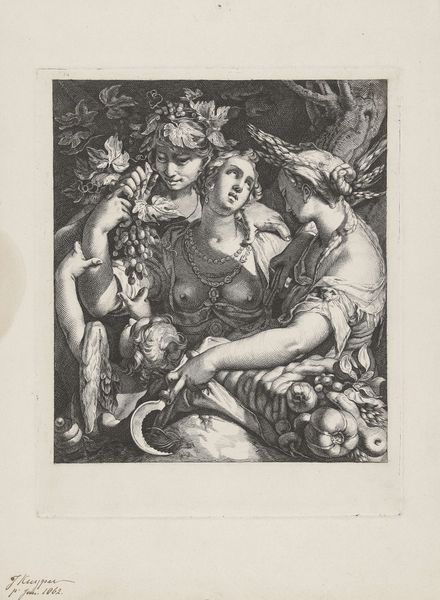

engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

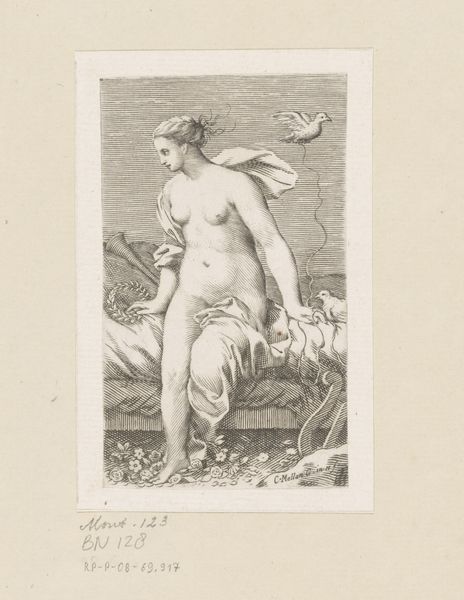

nude

#

engraving

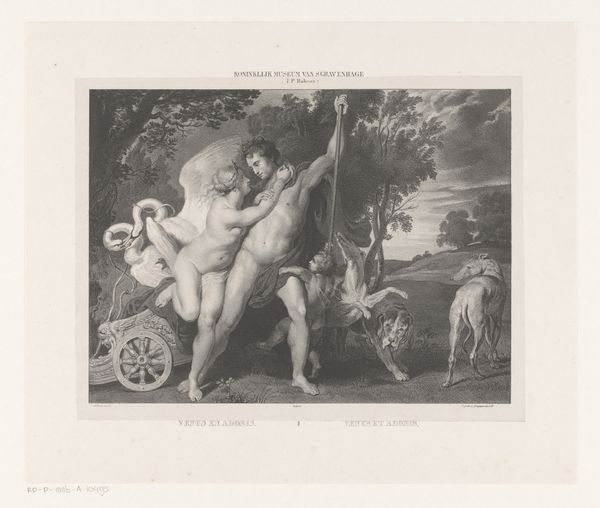

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 343 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

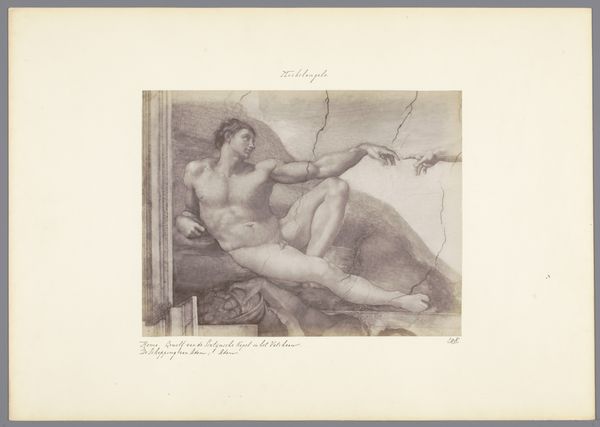

Curator: This print, titled "Apollo," was created by Cornelis Bloemaert between 1637 and 1692. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. The piece exemplifies the baroque style and is made from engraving. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the classical calm despite the baroque detailing. The musculature is wonderfully defined by line, but there's an almost melancholic repose. Curator: Well, it certainly draws upon classical allegories of male strength and beauty. But Bloemaert created this piece in a Dutch Republic undergoing major social and political shifts. He may be subtly commenting on the role of mythology in a changing society, grappling with questions of power, reason and religious change. Editor: That's a valid perspective. Though the allegorical component is crucial here, notice how the semicircular composition—its inherent curvature—adds a sense of enclosure and almost cradles the figure? I am intrigued by how Bloemaert manages to create so much textural variance using engraving alone. Curator: The rendering of Apollo in this nude form can be seen as an ode to enlightenment ideals. The sensuality, displayed freely, could symbolize a push against the suppression of pleasure by religious puritanism. His languid posture, almost deliberately nonchalant, could suggest privilege. The piece begs a discussion about accessibility and societal biases during that time. Editor: Yes, there is the figure as an iconographical component – this ode to idealized masculinity and its symbolism - and I can follow you on these suggestions on representation and social dynamics. Still, looking purely at technique, observe the intricacy of his hair and how this contrasts with the comparative smoothness of his skin. It gives such a strong sculptural quality to the overall image. Curator: Indeed. I also consider the gaze he casts, directed away, perhaps hinting at the shifting societal priorities that made the god of light, music, and arts seemingly disinterested. We can contextualize such depictions as a marker of society wrestling with emergent sciences. Editor: Very insightful. I've definitely developed a deeper appreciation for the dialogue between form and context here, thank you! Curator: My pleasure. Considering both historical currents and artistic intent always adds dimension to our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.