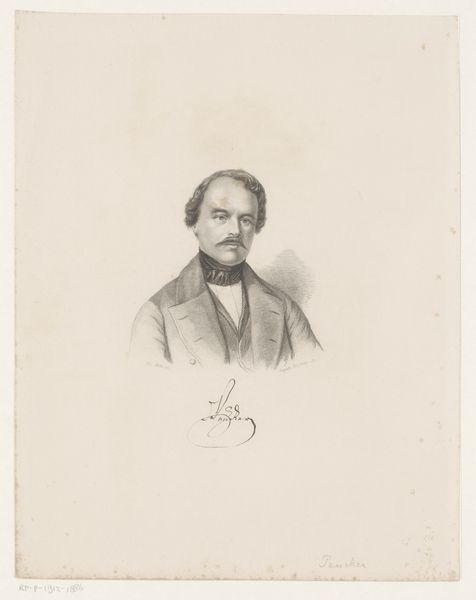

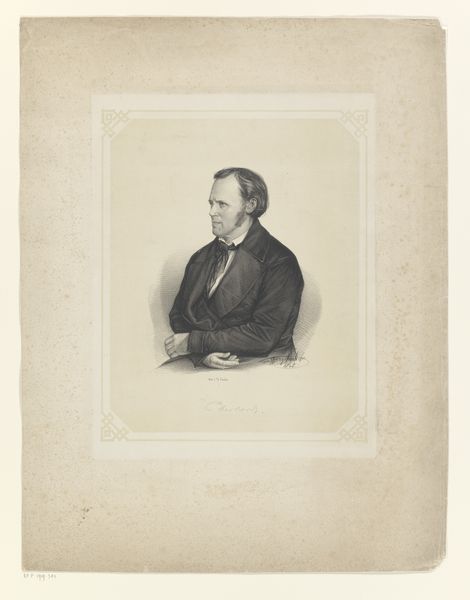

drawing, pencil

#

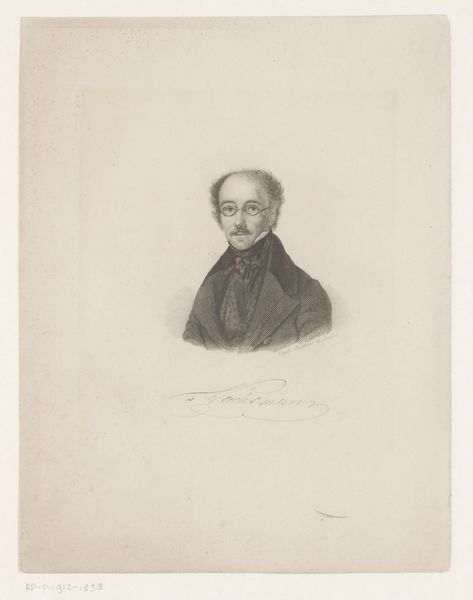

portrait

#

drawing

#

self-portrait

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Dimensions: height 249 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Charles Brias' "Zelfportret", a pencil drawing from 1846. It’s quite striking how much detail he captures with just pencil. What strikes you most about this self-portrait? Curator: Immediately, I see the assertion of artistic identity, but through a veil of melancholy. Notice how he presents the tools of his trade - the palette and brush. These aren’t merely props; they are signifiers of his profession, almost like emblems of belonging. But what feeling do those emblems evoke? Editor: A slight sadness, maybe? There's a softness to the lines, almost as if he is hiding himself? Curator: Precisely. Consider the artistic climate of 1846; Romanticism emphasized the artist's individual genius, yet also acknowledged their alienation. This portrait seems to navigate that very tension. The soft hatching gives the piece an almost ethereal quality. Is it a statement of self-assuredness, or something more vulnerable? Editor: So the symbols themselves are complex, then; like he's both revealing and concealing something? Curator: Think of how potent self-representation has been in art history. Artists use themselves as symbols. He holds the tools of his trade as if they are part of himself. Now tell me: do you believe the inclusion of a self-portrait speaks to legacy, or to an introspective observation of his self at that moment? Editor: I think it's both. Legacy because artists create artworks to last forever and also introspective because this feels deeply personal, right? Thanks! I'm not so familiar with symbol use of the period. Curator: Absolutely. Through studying the symbology within an artist’s own presentation of self, we gain insight into how cultural narratives are perpetuated – and also subtly subverted. I will note I learned a great deal about artistic intentionality from our discussion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.