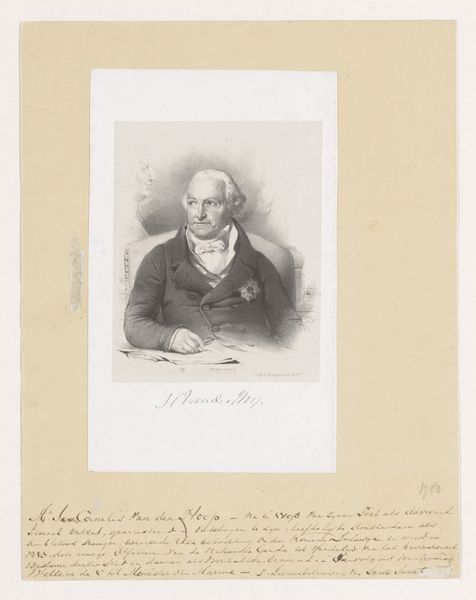

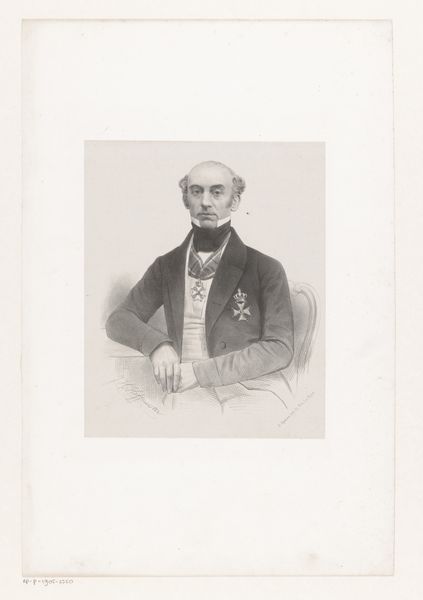

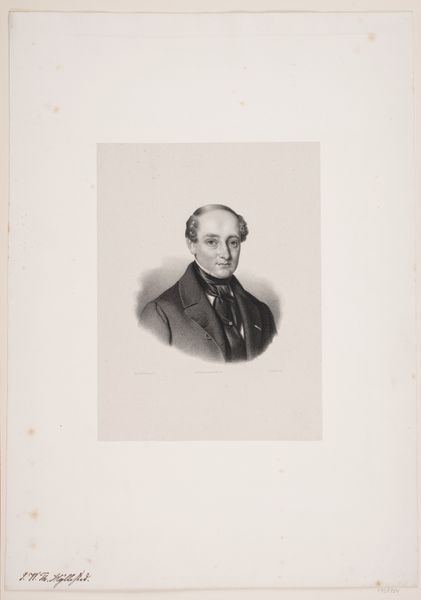

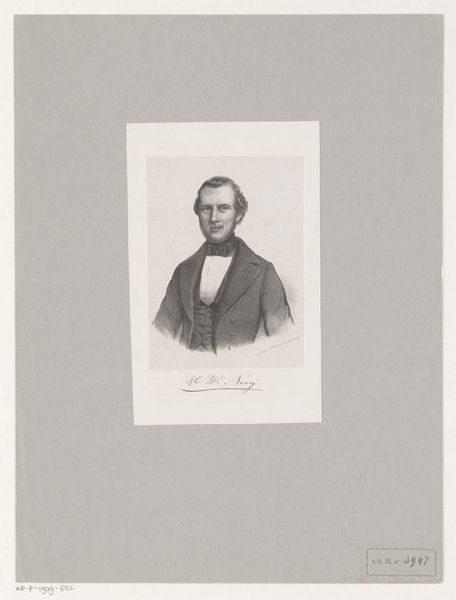

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 518 mm, width 355 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have "Portret van Geert Reinders," a print by Johan Hendrik Hoffmeister from sometime between 1851 and 1883. The engraving itself has a somber, almost austere quality. What strikes you about this piece? Curator: The stoicism is evident, isn’t it? Beyond the realism typical of the period, I see a statement about societal expectations placed on men. Think about the historical context – the 19th century was an era defined by rigid social hierarchies and burgeoning industrialism. Consider the gaze; does it invite engagement, or does it hold you at arm's length? Editor: It feels very… formal. He's definitely not smiling! Was this typical for portraits at the time? Curator: Absolutely. Smiling was seen as undignified in formal portraiture. More broadly, think about who had the privilege to be portrayed. Portraits weren’t simply aesthetic objects; they were markers of status, projecting ideals of respectability and power, particularly for men. What does this image say about Reinders’ social standing? Editor: Well, he's wearing a suit, so middle class, perhaps? It makes me think about the absence of women in positions of power during this time. Were they depicted differently? Curator: Precisely. Female portraits often emphasized beauty and domesticity. By comparison, men were presented as figures of authority, intellect, and industry, shaping not just their immediate environment, but society as a whole. This work is as much about gender roles as it is about Reinders. Editor: That makes so much sense. Seeing it as a social commentary, it completely changes my perception of what Hoffmeister was trying to communicate. Curator: Exactly! And thinking about portraiture as a performance of identity invites critical inquiry. What narratives are prioritized, and whose stories are deliberately left untold? This understanding helps us contextualize historical realities, giving visibility to subjugated histories and thus changing the landscape of the arts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.